|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

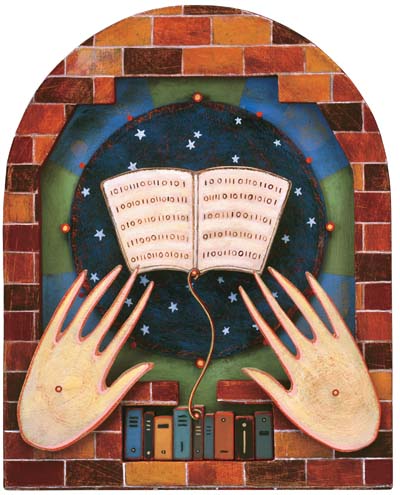

Digital DimondAre books passé in the electronic age?

by Clare Kittredge, '80G

Illustration by Maria Rendon

|

When Darlene Dube needs to look at a particular computer programming textbook for her computer science class, she just logs on to the UNH library web site and tracks it down through one of its electronic databases. She's done it at home at night on her laptop, sipping margaritas by the pool and reading Safari Tech Books online.

A junior in her late 40s, Dube is a nontraditional geography major living in Madbury, N.H. She is also a full-time program coordinator at the UNH Complex Systems Research Center, working with scientists who research global water issues. Not only do these researchers access articles online, but the scientific journals they publish in are available through the library via a whole slew of online databases, she says. "On another level, I'm also a student here. Through digitization, professors can make certain textbooks available online for students without their needing to purchase them, and that's huge. I saved $30 to $50 reading this textbook online."

The digitization Dube is talking about is a phenomenon that has utterly transformed the way we acquire information. At the UNH Library, the revolution has changed the way pictures, music, and the text in books, journals and newspapers are stored and disseminated. It is putting access to a whole universe of knowledge at a user's fingertips, including books and journals UNH doesn't actually have.

"Everything is different," says Claudia Morner, dean of the University Library, gazing out of her office at a vista of brick academic buildings. "Yes, we're still buying books and periodicals and checking books out. But we're using technology a lot more than we used to, and that's really changed what it means to work and study here."

Many professors and alums can remember the sudden freedom from having to rummage through dog-eared index cards and jot down Dewey Decimal System numbers to track down books when the library card catalogue went online in the late 1980s. That marked the beginning of computerization at the library. Digitization—based on digital imaging technology—is putting information into electronic form so it can be retrieved by computer or online, and the National Science Foundation declared the first Digital Library Initiative as long ago as 1993. But in the last decade, the pace and the volume of digitization have picked up.

UNH digital collections librarian Eleta Exline stands at a library computer and demonstrates. Around her, computers hum and keyboards tap as students check e-mail, work on assignments and study for exams, all online. Exline clicks her mouse, and up pops a collection of early New Hampshire broadsides and proclamations. Their decrepit yellow pages, frayed edges and all, hover on the screen, denouncing heresy and inciting fasting.

At Exline's command, the broadsides disappear, replaced by the image of a boy shaped like farm animals squashed together. This is "The Boy Made of Meat," a curious poem by a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet that went unpublished until a passionate New Hampshire educator, the late William Ewert '65, '69G, discovered it and published it himself. The cover shows the reddish boy—part fish, part sheep, part chicken. Another click, and up pops a hand-scrawled lamentation by poet W.D. Snodgrass about all the meat boys are forced to consume to become men.

Next is a black-and-white photo of Ralph Page, dean of New Hampshire contradance callers. On the screen is the worn cover of the first issue of Northern Junket, a periodical Page single-handedly edited in wobbly handwriting for all to see: Vol. 1, No. 1, April 1949.

And those are just a few snippets from the library's online collections. Today's digitized library offers UNH students and faculty members a dizzying array of ways to get data. These include electronic databases, from MathSciNet to The New York Times back to its start in 1851.

Although the concept is still in its infancy, there are also thousands of classic e-books available free in the public domain, says Morner. Alumni from even as recently as the '90s can probably remember when they would go to the library for a book on reserve and find all the copies had been checked out. In the digitized library, professors can put a book on electronic reserve. Today, UNH faculty and staff members and students have online access to 21,000 periodicals. The library still subscribes to 5,333 print periodicals and another 20,000 government documents, but the use of paper periodicals and newspapers is plummeting. While the number of books put on reserve dropped nine percent in 2005 from the year before, electronic material on reserve for student use increased by 25 percent.

David Watters can remember toiling in the semi-darkness of a "cavelike" back room in the library, hunched over aging microcard machines to read early copies of the New England Primer, the first American schoolbook. Back then, microcards reproduced the book on postcard-sized cards. Watters, a UNH English professor, spent almost a year laboriously feeding the cards into the machine and holding each one down on the lens so it would be in focus, struggling to take notes with his other hand. It was "appalling," he says, and almost impossible to get students to use the machines.

Today, Watters has instant online access to all the books printed in America before 1800, and everything from temperance to witchcraft. With a few more clicks, images of pages of The New England Primer bloom on his computer screen. And he can search them too. "Let's say I was interested in attitudes toward the deaths of children, as a person interested in New England gravestones," says Watters, who directs the Center for New England Culture at UNH. "I can search for gravestones and death, and every little rhyme and poem about it, every prayer or dialogue in the primer is suddenly produced." He can download an issue for his students to read or tell them to log on and go read it. "The learning experience is so much more exciting today because it's immediate," he says.

Physically, Dimond Library reflects the technology that has changed it. As part of its renovation eight years ago, it was wired with jacks for Internet access and 18 computers for public use.

Then wireless Internet access came along. Today, the library has 144 public computers, and all its student study spaces have wireless access. The reserve desk loans out 15 wireless laptops, four hours at a time, to students and faculty members.

Page: 1 2 3 Next>Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus