|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Grape ArdorPage 4 of 4

Fermentation changes the sugar in grapes into alcohol. The yeast that's on the grapes and in the air could make this transformation alone—because, as Gulyash says, "Winemaking is just nature's way of spoiling something." But natural yeast is unpredictable, so winemakers choose from hundreds of kinds of cultivated yeast, each of which adds different tastes and aromas. Fermenting and aging at Grove Street happen in 30 tanks ranging from 1,000 to 28,000 gallons, plus hundreds of barrels holding about 300 bottles of wine apiece. In simplest outline, white wines head out the door about nine months after the grapes came in. Red wines take about two years, which Gulyash says is long in contemporary California winemaking.

|

After aging comes the bottling line, which Paul calls "the last place you can screw something up." A filler pumps filtered air to clean the bottles, then pumps in nitrogen to eliminate oxygen, the enemy of wine. Wine flows in through a vacuum valve that pushes out the nitrogen. In the next machine, jaws compress the cork so that plungers can force it in. The corked bottle moves to a person, who drops the "capsule"—it looks like a long foil thimble—over the top. Machines crimp the foil and apply the labels. Two minutes after it started filling, the bottle is complete. The work on the line isn't romantic, but it's crucial. In the new wine economy, which Gulyash describes as "monstrously tougher than 10 years ago," some owners believe beautiful surroundings will distinguish a winery; Grove Street doesn't. "All we really need is a warehouse," he says, "because what matters is what happens inside."

Leaving Grove Street, Paul takes the scenic route through the Russian River vineyards. Like the vine flowers, which on this spring day have just begun to set, his life and work are entering a new stage. At about $1 billion in loans last year, "Paul Fi" is still small in industry terms, but he's confident it will find its niche the way Headlands did. The winery is small too, with 16,000 cases sold last year, but signs are good: Recent jazz concerts in the tasting room drew crowds, and two "super-premium" reds are selling well under the Peter Paul label (which, unlike Grove Street, isn't limited to $20).

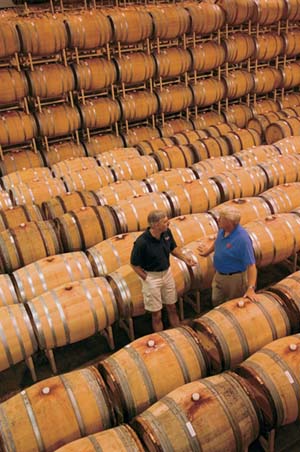

THE WAIT: The point at which wine has aged enough is gauged by winemaker Mikael Gulyash, left, with owner Peter Paul '67.

THE WAIT: The point at which wine has aged enough is gauged by winemaker Mikael Gulyash, left, with owner Peter Paul '67.

|

In his non-work life, his daughter is grown and on her own. At 62, Paul feels young but conscious of time. "I have years, but maybe not 20 years," he says. "I have answered to no one since '86, so I'm probably not employable." That's a joke; he knows he'll never have a boss again. In fact, his challenge now is realizing that his businesses don't need to succeed. "It's interesting to get past the point where it matters," he says. "That's an adjustment."

Ten minutes into the drive, his cell phone vibrates: He's left his briefcase at the winery. "No, don't bring it," Paul tells the caller. "I'll come back." He's been barreling full-speed ahead during this conversation but hangs up and reverses direction. After just a few miles, an oncoming red station wagon flashes its lights. Paul pulls over quickly. Gulyash jumps out, strides over to Paul's car and wordlessly hands the briefcase through the window. Paul drives off again. Later, an attempt at a shortcut will leave him stuck behind a paving crew with his whole body jittering impatiently. Right now, though, the sky is clear, the road is open, and everything's in its place. It's a beautiful day to explore wine country.~

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 4

Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus