|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Into the WoodsPage 2 of 3

HUNTER CARBEE '90, '93 started cutting trees for a living when he was in his early 20s. For 10 years he worked as a logger, heading into the woods every day with his chain saw. He loved his job—the beauty of the woods, the physical challenge, the solitude. And then, one day, it was over. At 10 in the morning on May 9, 1988, a 60-foot black birch hit him from behind, pinning him to the ground and crushing his pelvis. "I never saw it coming," says Carbee, who knows four loggers who have been killed by falling trees. "I should be dead, too," he says. "Or at least paralyzed." Carbee was lucky. The accident happened close to a road. His two buddies managed to cut him free and get him into the back of a pick-up truck. By 1 p.m., he was in surgery. For three days he hovered between life and death, gradually stabilizing and beginning the long road to recovery.

|

Nine months after the accident, leaning on a cane, Carbee enrolled in UNH's Thompson School, the first step to a new career. "The T-School taught me how to be an on-the-ground forester," says Carbee, who for months couldn't sit down for more than 30 minutes at a stretch before the pain became unbearable. He knew he couldn't cut trees anymore. So instead he learned to find boundary lines, lay out timber sales, and identify tree species.

When he finished his two-year degree in the Thompson School, Carbee kept going, earning a four-year forest resources degree from UNH's College of Life Sciences and Agriculture. There, he gained a background in forest economics and policy that taught him how to evaluate the big picture. "When you're working with a number of goals—recreation, water protection, timber management, wildlife—you have to think about how to balance everything. It comes right down to the individual tree, when you're deciding whether it stays or whether it goes."

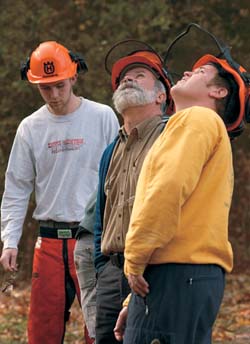

The minute he graduated, Carbee went to work as a forester, returning to the woods he loves and walking miles each day as he marked boundaries and trees. The walking was part of his ongoing rehabilitation, preventing the severe arthritis doctors predicted would eventually set in. When he later took a job as program director for the New Hampshire Timberland Owners Association, Carbee became famous for his logger safety classes. The presentations he gave always included the facts—that logging is the second most dangerous occupation, ahead of fire fighting, coal mining, and high-rise construction. Only commercial fishing ranks higher. When Carbee told his own story, the roomful of loggers, many of them cocky and sure of themselves, always fell silent. "By the time I was finished, you could hear a pin drop," says Carbee, chuckling.

Today, 20 years after graduating, Carbee works as a wood buyer for two wood-fired co-generation power plants in New Hampshire. It's a niche he predicts will take off as the cost of oil and gas continue to rise. It's also proof, says Carbee, of the changing shape of the forestry industry. "When I was logging, this market wasn't even available," he says. "Back then, you mostly 'cut the best and left the rest.' This new market means you can use the diseased, malformed trees, leaving the stronger ones to grow. It's an excellent tool in terms of managing a forest."

|

Shifting markets—from the opening of new wood-fire energy plants to the closing of paper mills—aren't the only recent changes facing the industry. Just a generation ago, says Carbee, logging was still primarily a chainsaw and skidder operation. "It was all hard manual labor," he says. These days, it's highly technical. "We have machines that cut the tree and machines that limb the tree. We work in small two- or three-man crews. Everyone runs more than one machine. It's all very efficient." But—good news for graduates—Carbee sees no reduction in the need for labor. "The job market is great right now," he says.

Ironically, the UNH forestry programs are small at the moment, reflecting a current downswing in forestry programs across the country. "There's a real perception out there that forestry is a flannel-shirt-and-suspenders, knuckle-dragging sort of thing," says Mark Ducey, associate professor and forestry program coordinator in the department of natural resources. "Well, yes, lots of us wear flannel shirts—they're comfortable." But, there's also this new high-tech side to forestry. Any student who's good at those things can walk into a really good job. It's a great time to be a forestry major."

Jen Weimer '02, '04 is one of those recent high-tech forestry alums. Like Carbee, she continued with the four-year program after graduating from the Thompson School. "The two programs work really well together," says Weimer, who is one of two forest health specialists with New Hampshire's Division of Forests and Lands. (The other is Kyle Lombard '87, '90.)

Weimer already had a bachelor's degree in art and photography when she enrolled at UNH at age 27. Now, instead of photographing the woods, she's helping to save them, flying over the state, mapping insect damage from the air. She uses high-tech tools like a GIS computer-mapping program that incorporates multiple layers of data, including stream locations, road systems and ownership information. "We make our own layer about pest damage we see and then put all the layers together to determine where the hot spots are and what needs to be done."

A recent survey indicates 111,000 acres of damage from the forest tent caterpillar, which defoliates oaks and sugar maple. "We haven't had this much damage since the gypsy moth outbreaks in the 1980s," says Weimar. Her career began, she says, simply with a love of the outdoors. "But the more I look at it, the more I realize that what I'm doing has real purpose. You feel that you're doing something good."

Page: Prev 1 2 3 NextEasy to print version