|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

A Matter of Common SenseIf we don't take care of the Earth, and our culture, who will?

By C.W. Wolff

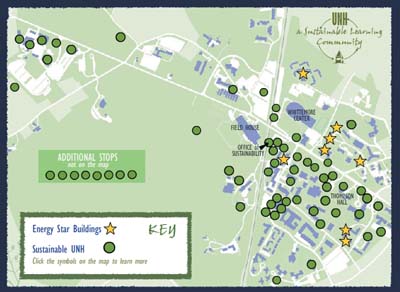

For a campus illustration and examples of sustainability at UNH, click here.

|

IT MAKES SENSE that the endowment for UNH's sustainability program—the first of its kind in the country—came from a farmer. The late Oliver Hubbard '21, who gave the university $10 million in the mid-'90s, grew up on a New Hampshire farm long before the words "organic" and "sustainable" were in vogue. But that's what those early farms were all about.

"We didn't call it that," says Charles Schwab, a UNH professor of animal and nutritional sciences who was also raised on a farm. "But that's what it was. It was about taking care of the soil to produce good feed to take care of the animals—who then took care of you. You learned to work the entire system without a lot of supplements and chemicals... Sustainability is a matter of common sense."

It also is a matter of defining what really sustains human civilization and understanding the interdependence of systems—not just on a single farm, but globally. Not to mention good business practices and wise use of resources.

"Hubbard understood that a university is all about intellectual, critical learning and pushing the edges of how the world works," says Peter Lamb '76, a University System of New Hampshire trustee who helped secure the sustainability endowment. "He recognized sustainability as a concept that could change the entire university long term." And he understood the role universities play in changing the world.

For more information, see www.sustainableunh.unh.edu. Check the site often because the list of projects is growing. Also see an online map of sustainability at www.unh.edu/map/sustainabilitymap.html. |

Because of the Hubbard endowment, sustainability initiatives have been reaching most parts of campus for more than a decade, bringing people together across disciplines, departments and colleges, and setting UNH on the path to being recognized as a sustainable learning community in the same way that it's known as a land-, sea- and space-grant institution.

AT UNH, sustainability initiatives cut across what Tom Kelly, UNH's chief sustainability officer, has coined the CORE—curriculum, operations, research and engagement with the state and region.

"Greening—the old environmental notion of being more efficient and getting rid of chemical pollution—covers only the 'O' of CORE," says Kelly. "It's important, but we could make a campus 'green' and never think about what and how we're teaching and researching and whether or not it's responsive to the challenges of sustainability."

According to Kelly, that challenge involves maintaining the integrity of four broad, interlocked systems: biodiversity, climate, food and culture. At UNH, the scope of those four systems takes in just about everything—whether it's public art or a pipeline that will soon deliver methane to UNH from a Rochester landfill. In fact, there's a list of 32 sustainability initiatives on the University Office of Sustainability's extensive web site, and many link to a network of related projects.

"If you look around, the whole university is organized around sustainability, and it's not the cheap, 'Hey, recycle your cans and everything will be fine' kind," says Stephen Trzaskoma, associate professor of classics. At Kelly's suggestion, the classics department helped create an interdisciplinary, interactive exhibit in the MUB, connected to photovoltaic panels on the roof, which explored the science of the sun and its central role in the Earth's existence, art, culture and mythology.

Page: 1 2 Next >Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus