|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Turning the TidePage 2 of 2

"I'm sorry you have to live this way," I told him. "My father has six daughters. I can't imagine him knowing that he couldn't keep me and my sisters safe."

The embassy driver slowed as the SUV bounced along the narrow cobblestone streets of Olinda (Portuguese for "Oh Beautiful!"). Founded in 1535, the colonial city rests on a hill, offering panoramic views of historic churches, orange-tiled rooftops and the blue waters of the Atlantic. In one of the city's hotels, I met with 60 journalists from TV Globo, one of Brazil's largest television stations. An interpreter translated as I talked about stories I had written, stories that had changed laws and lives.

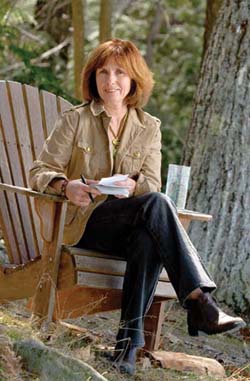

ACCORDING TO AN OFFICIAL at the U.S. Consulate in Recife, a major Brazilian newspaper changed the way it reports crime and violence after a visit by Barbara Walsh '81. |

One of the biggest learning experiences of my career, I told them, was the Willie Horton story. Horton had been sentenced to life in prison for stabbing to death a 17-year-old boy during a gas station robbery. In 1987, the newspaper I worked for, the Lawrence (Mass.) Eagle-Tribune, discovered that Horton had escaped while on an unsupervised weekend pass. He fled to Maryland, where he held a young couple hostage, raping the woman twice and repeatedly stabbing her fiancé.

Prison officials, I explained to Brazilian journalists, weren't eager to give me information about their furlough program or why a killer like Horton was let loose for the weekend. Massachusetts authorities insisted that their program was similar to other states. I did my own survey, calling prison officials in the other 49 states.

"Other reporters in my newsroom thought I was nuts for wasting so much time on one story," I said. "But I learned Massachusetts' furlough program was one of the most liberal in the country. My story outraged people in the state, who eventually made sure the furlough program was changed."

I knew that Brazilian journalists had laws that worked against them, laws that kept many records secret; American reporters, I explained, faced similar challenges. "You can't give up or go away because the government won't give you answers," I said. "You have to find another way to get the information."

The reporters wanted to know how I would cover murder in their country. How would I write about 54 murders in a weekend or the 1,095 murders that occurred in Recife in one year?

I told them I would do it one story at a time.

A few days before I arrived in Brazil, a man had been killed by a "lost" bullet as he pumped gas. The bullet had been fired blocks away by drug dealers engaged in a turf battle. The reporters explained that a lot of innocent Brazilians lose their lives to these lost bullets.

"Who was this man who died at the gas station?" I asked them. "Was he a father? What were the last 24 hours of his life like? Did he hug his children goodbye that morning? You've got to get the details to make his story unforgettable. Your politicians need to be reminded, pressured about these kinds of murders, and this is the type of story that can do that."

I met many courageous and passionate journalists while visiting Brazil. One of them was Maria Luiza Borges, editor of Jornal do Commercio. The day I spoke to her staff, Borges' newspaper had begun publishing a series on Recife's crack cocaine trade. Unhappy with the stories, drug dealers had threatened to kill the small boys who hawked the newspaper in the streets. The reporter and photographer who worked on the series had gone into hiding for their safety. "We are very afraid," the editor told me.

Editors like Borges have good reason to fear drug traffickers. In 2002, they tortured and killed a TV journalist who was investigating the drug and underage sex trade in a Rio de Janeiro favela.

Brazilian drug dealers are often better armed than the police, and like most Brazilian criminals, they are rarely convicted. Though I had written many stories about criminals, killers and drug dealers in the United States, I had never been threatened; I didn't know what it was like to risk your life for a story.

During my five days in Brazil, I traveled to the north, central and southern part of the country and spoke to more than 400 newspaper, TV and radio journalists. Many of them believed that they could make their communities safer and less violent through their reporting. Still, they were daunted and sometimes overwhelmed by the task.

As I waited in the São Paulo airport to fly home, I thought about the father, Alfredo, and the millions of other Brazilians like him who have to barricade themselves in their homes or armored cars to feel safe. I felt guilty about returning to my home state of Maine, which averages about 25 murders a year-the number of homicides that occurred in Recife during a single day.

Now, seven months after my trip to Brazil, I still keep in touch with journalists there. Their e-mails speak of hope and perseverance. Editor Borges recently updated me about her paper's coverage on Recife's drug trade. After the paper's series drew threats from drug dealers, police offered Borges' staff protection for a month, patrolling the building and its parking lot. The newspaper also wrote more stories, reporting that nothing much had changed in "Crackland," where drugs were sold openly in daylight.

"The authorities haven't done much to solve the problem," Borges wrote. "But I am an optimist. I have faith that someday things are going to be better. Hopefully, I will live to see that." ~

Barbara Walsh '81 is a journalist in Maine whose articles on the Willie Horton Jr. case prompted a change in laws governing the Massachusetts furlough system and won a Pulitzer Prize in 1988. In 2007, she received the Yankee Quill Award.

Page: < Prev 1 2Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus