|

|

| current issue |  | past issues |  | send a letter/news |  | address update |  | advertise |  | about us |  | alumni home |

Features

Riot ActPage: < Prev 1 2 3 4 Next >

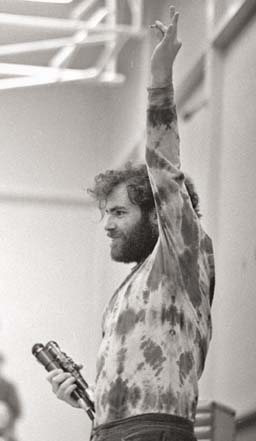

JUST DO IT: Jerry Rubin salutes the crowd with a joint. |

The onslaught of news stories and editorials only helped activate the campus. "If Loeb don't like it, do it!" was printed on a red blanket and hung for weeks outside an upper-story Stoke Hall window. (Jerry Rubin had just published Do It! Scenarios of the Revolution.) What students didn't know was that John Scagliotti '70, feigning outrage, had tipped off the Union Leader to the planned event. He was part of a small "kitchen cabinet" of friends who supported Wefers and helped plan the visit.

While most critics, including a majority of university trustees and administrators, stopped short of saying the Chicago Three had no right to speak at UNH, they generally agreed that student fees should not be used to pay the speakers. Originally, Wefers believed the funding would come from excess advertising revenue from The New Hampshire and the Granite, plus other money from MUSO and student government. Citing student organization regulations, the university administration blocked the first two sources. The UNH chapter of the conservative student group Young Americans for Freedom blocked the third revenue source in court with the help of Chuck Douglas '65, a young Manchester lawyer and future U.S. representative and state Supreme Court justice.

"The bone we were picking was balance in speakers," recalls Lon H. Siel '72, one of the YAF students who filed the suit. "If they had also been booking William F. Buckley Jr., we would not have had a problem." Ironically, Wefers had actually attempted to engage the high-brow conservative icon—the very antithesis of Abbie Hoffman—earlier in the semester, but Buckley commanded a $10,000 fee and was booked years in advance.

Funding issues became moot, however, when the Chicago Three promised to speak whether or not they were paid, and the controversy shifted to concerns that they might incite a riot.

Pretty soon everybody wanted in on the act. The mayor of Manchester condemned the event, and the state House of Representatives passed a resolution calling for the university to deny the Chicago Three use of any campus facilities. Loeb editorialized that the most appropriate venue would be "the nearest open sewer."

TRADING PAPERS: U.S. Marshall Victor Cardosi, in hat, serves Mark Wefers '73, seated in the center, a subpoena to appear in court; Wefers hands him a petition signed by more than 2,000 students who asked to be named co-defendants. Students standing in the rear include Dana Gordon '72, second from left. Richard Lewis '70 is seated at right. |

Realizing the whole thing was not going to go away, UNH President John McConnell asked the University Senate's student welfare committee to determine if a university policy banning speakers who "advocate the violent overthrow of the government" would be violated. The committee concluded, with legal advice, that even if that were the case, the policy was not consistent with the First Amendment.

The fairly new, and unusual, University Senate—its ranks including students and members of the faculty and administration—received the committee report and voted to support the Chicago Three appearance. President McConnell also contacted 36 colleges where Hoffman, Rubin and Dellinger had spoken in recent months to see if they had "incited riot." He found they had not.

McConnell had a strong background in labor arbitration, and according to Brockelman, was an enlightened leader who "would never freeze, panic, or get all emotional or ideological." He had stated that he would make the final decision on the visit of the Chicago Three, but he wanted the buy-in of all the trustees. He prepared an eight-page report and presented it at a marathon trustees' meeting that began on Friday, May 1.

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 4 Next >Easy to print version