|

|

| current issue |  | past issues |  | send a letter/news |  | address update |  | advertise |  | about us |  | alumni home |

Features

|

Real New Hampshire

Champion of farmers, Steve Taylor '62 is known for his wit, his list and his common sense. |

Easy to print version |

Perry Smith/UNH Photographic Services |

Paul Franklin was just 23 when he was elected to the Plainfield board of selectmen, and within four days he found himself standing before a crowd in the school gym, expected to speak intelligently about a warrant article. More than 30 years later, Franklin, an apple grower, still recalls his anxiety. "Was I nervous? Twenty-three years old in front of all the people I grew up with and my parents? You betcha," he says.

Fortunately, he was sitting next to a more-seasoned selectman, Steve Taylor '62. Just as Franklin was about to rise from his chair to speak, Taylor leaned over to offer some last-minute advice.

"Talk loud, boy," Taylor said. "They'll think you know what you're talking about."

Anyone lucky enough to get a seat next to Steve Taylor is bound to come away with something, be it a little rural wisdom disguised as a wry joke, a revealed connection between past and present or a lesson in how to run a meeting. In his 25 years as the state's commissioner of agriculture, Taylor earned a lasting reputation as the rarest of leaders, a canny Yankee farmer able to move effortlessly between barn and boardroom, sometimes without even changing out of his work boots. His affable personality, common-sense approach and folksy style elevated him to the level of a treasured New Hampshire institution.

Taylor just finished a record-setting tenure as an ex officio member of the University System Board of Trustees. Politically skilled without being political, Taylor weathered six changes of administration—from Hugh Gallen to Jeanne Shaheen—by first earning the steadfast respect of farmers, then gradually winning over the rest of the state.

"His breadth of knowledge cuts across geography, society, business, all interests," says Betty Hoadley '57, '72G, a retired teacher and former state representative who joined the board in 2006. During a Thompson School graduation, Hoadley happened to look down the row of fellow trustees, all in their sober black robes. There sat Taylor, his legs crossed just enough to reveal a pair of high-top work boots sticking out from under his robe.

Perry Smith/UNH Photographic Services |

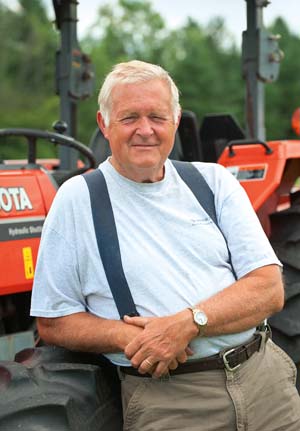

Though he retired as commissioner in 2007 (a loss the Concord Monitor equated to "watching a shopping mall go up where the woods you played in as a kid once stood"), Taylor, 71, remains as active as ever. True, he's winding up 31 years as Plainfield town moderator, passing the role to Paul Franklin, now a practiced public speaker. But drop by the Taylor Brothers Sugarhouse and Creamery in the Meriden village of Plainfield, and you're more than likely to see a tall, white-haired guy, suspenders stretched over his T-shirt, out spreading manure, fixing a tire, or, if it's a Sunday or Monday, milking the cows. The Taylors have 60 head of Holstein milking cows and an equal number of heifers, which he calls "ladies in waiting."

The 166-acre farm includes cow barns, a creamery and a bright red sugarhouse and store. Taylor and his wife, Gretchen Schnare Taylor '62, live in the farmhouse, where they share an office and watch the Red Sox side by side in matching armchairs. Their friendly schnauzers, Katie and Theo (after Red Sox general manager Theo Epstein), have the sofa to themselves.

"People say, 'You could make a lot more money doing other things than farming,'" Taylor says as he drives a visitor past nearby fields and meadows in his red pickup. "And I say, 'yeah, but I couldn't do this,'" he continues, waving one sturdy arm as if to capture the pastoral landscape rolling by. "There is nothing greater than to be on a tractor and mowing around and around. You can daydream and just think about all kinds of stuff. I just love it."

Perry Smith/UNH Photographic Services GOT COWS: The Taylor farm has 60 milking cows and 60 heifers, which Steve Taylor '62 calls "ladies in waiting." |

Taylor started out as a reporter, and given his ear for storytelling and seemingly photographic memory, he might have easily risen through the ranks to a plum job with a major metropolitan daily. A political science major at UNH, he edited The New Hampshire in his senior year, then after graduation quickly moved from cub reporter at the Portsmouth Herald to managing editor of the Valley News. After seven years, he went freelance and roamed the state for the now-defunct New Hampshire Times, turning in pieces about fading local dialects and the origins of the working man's beer joint. At one point in his career, the Boston Globe came calling, but Taylor decided he didn't want to spend all his time chasing stories, especially if the chase took him out of the countryside. "I had a bunch of other interests, things I wanted to do," he says. "I'm still that way."

Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus