|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Only in New HampshirePage 2 of 3

First Fever

Sen. Joe Lieberman responds to a question from a student at an Every Child Matters forum in Huddleston Hall.

Sen. Joe Lieberman responds to a question from a student at an Every Child Matters forum in Huddleston Hall.

|

A self-described "incorrigible political junk-ie," assistant professor of political science J. Mark Wrighton is unabashed in his enthusiasm for the theater of the New Hampshire primary. When he co-taught the course on the primary, he peppered the 86 students in the class with dozens of e-mails, liberally strewn with exclamation marks, about opportunities to meet candidates, participate in nationally televised campaign forums and become volunteers or interns. He also kept them abreast of the online voting in the Mrs. Kucinich Contest. ("YOUR vote could make the difference in THIS election!!!")

Originally from Louisiana--his license plate reads KJNMAN, for Cajun Man--Wrighton came to UNH three years ago by way of Texas and Iowa, where he received his doctorate. So he speaks with some authority when he says the class "just wouldn't work anywhere else--not even Iowa."

That's because New Hampshire is a small state, he says, and the people "who are doing this kind of work in the real world" are willing to give their time to interact with students. When Anna Barbara "Bobbie" Hantz '77, former executive director of the state Republican committee, spoke to the class about fund raising, Smith and Schroeder spent nearly an hour talking with her after class and continued a dialogue with her by e-mail.

As a scholar, Wrighton studies--and loves--some of the most unlovable parts of politics, like special interest groups ("It's redundant. All interests are special!"), negative ads (he prefers the term "comparative ads") and the "soft money" used to pay for them. Officially registered undeclared like nearly 40 percent of the state's voters, Wrighton has decidedly Republican tendencies. In that regard, he is unusual in an academic field where nationally an estimated 90 to 95 percent of professors are liberal Democrats.

As columnist David Brooks recently pointed out in the New York Times, conservative applicants to graduate school in political science are sometimes urged to stay "in the closet,"or, as one Harvard professor quipped, just "go to Washington and run the country instead." But Wrighton fits comfortably into the UNH political science department, which has a healthy diversity of political viewpoints.

The other half of the duo teaching the primary course was the mild and fact-filled Andrew Smith, director of the UNH Survey Center. In part because the survey center has had the best record of predicting the outcome of the primary over the years, Smith is in demand for political commentary, spending three to five hours a day on the phone with reporters, media clients and campaign staffers during election season.

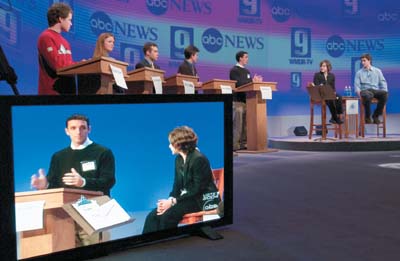

Junior Jamieson Scott (on monitor in foreground) stands in for Sen. Joe Lieberman during a sound check for the nationally televised Democratic presidential debate held at UNH in December. Scott was one of more than 50 UNH students who helped out, building wood podiums, acting as "interns for a day" with ABC News and C-Span or assisting in the candidates' "rapid response" rooms.

Junior Jamieson Scott (on monitor in foreground) stands in for Sen. Joe Lieberman during a sound check for the nationally televised Democratic presidential debate held at UNH in December. Scott was one of more than 50 UNH students who helped out, building wood podiums, acting as "interns for a day" with ABC News and C-Span or assisting in the candidates' "rapid response" rooms.

|

Smith, who resembles a tweedy Peter Jennings, hopes students who took the primary class or got involved in a primary campaign have learned "how important the political process is, how important the New Hampshire primary is in the selection of the president--and how different New Hampshire is from the rest of the country in how it goes about voting."

The first invited speakers in the weekly three-hour class were former Republican Gov. Hugh Gregg (who died several weeks later) and longtime Democratic Secretary of State Bill Gardner, co-authors of the 2003 book Why New Hampshire? Contrary to popular belief, New Hampshire's primary has been first almost since the beginning of presidential primaries in the United States. It was originally scheduled to coincide with the traditional town meeting in March, thus in true Yankee fashion "saving money by not heating the town hall twice," according to Gregg and Gardner.

Although it's been first since 1920, New Hampshire's primary didn't draw national attention until 1952, when the state tried to raise voter turnout by adding a nonbinding "beauty contest" in which voters could vote directly for candidates. Suddenly the primary performed the function of an early poll, indicating which way the political winds were blowing.

Over time, New Hampshire citizens became not only extremely likely to vote but also extremely savvy voters. In their book, Gregg and Gardner argue that the state now deserves to be first, and offer many examples of experts who agree with them, such as Harvard's Thomas Patterson. "The turnout rate in New Hampshire is nearly twice as high as in any other state and its residents take their role seriously in other ways," Patterson has written. "One study found they were 100 percent more likely to have particular knowledge of primary election candidates and issues than other Americans."

Primary Central

On Dec. 9, in preparation for the evening's nationally televised Democratic presidential debate, ABC News held a rehearsal and sound check at Johnson Theatre. A question on his domestic-policy platform was lobbed in the direction of the podium marked "Wesley Clark."

"I have no idea what my domestic policy is," replied the candidate. "I probably should, as president. I do want to make sure every student gets to go to college at little expense--in fact, it should be entirely paid for by the taxpayer!"

The "candidate" was Elliot Schultz '05, one of nine UNH students who stood in for the real contenders. "Interns for a day" for ABC and C-Span, the students worked behind the scenes, watched the debate from much-coveted theater seats and then rubbernecked in the "spin room," where the candidates held forth, surrounded by mini-mobs of reporters and cameramen.

Watching the debate live, Wrighton caught things the TV cameras missed--like a moment when Sen. John Kerry glanced at his watch. Wrighton was reminded of the time when George H.W. Bush looked at his watch during his 1992 debate with Bill Clinton, a gesture widely construed as lack of engagement and evidence that Bush had lost the debate. A few moments later, however, Howard Dean confessed that he had looked at his watch and noticed, with only 12 minutes remaining, that little had been discussed other than Iraq. His comment immediately prompted a shift to domestic issues. "They both did it, but Dean was able to make something of it," noted Wrighton.

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 Next >Easy to print version