|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Paulo Mongkuier, center, and his wife, Victoria Yak, shown here with their young daughter Arob, fled civil war in Sudan. Paulo's nephew, Agwik, lives with them.

Paulo Mongkuier, center, and his wife, Victoria Yak, shown here with their young daughter Arob, fled civil war in Sudan. Paulo's nephew, Agwik, lives with them.

|

Page 2 of 3

To learn the details of Nhat's life, Guldbrandsen has spent hours talking with him, asking questions and carefully listening. He has studied photo albums. He has been invited to family dinners and celebrations. "Lots of times what we do doesn't look much like research," admits Guldbrandsen, who carries a tiny pad in his back pocket on which he occasionally jots notes. For the most part, though, he observes and tries to be as unobtrusive as possible. When he gets back in his car to drive home, he turns on a digital recorder and recounts the details of his recent visit.

Just "being there," notes Guldbrandsen, is a big part of the research process, which is necessarily slow and circuitous. While participants are aware of the project and have given their consent, people don't just automatically share their life story. It takes patience, trust and time. This approach to research, known as "participatory observation," can have a profound impact on one's personal life. Glick Schiller, for example, has countless friends who began as research subjects, people she got to know because she found ways to participate in their lives--taking them grocery shopping, dropping in to chat so they could practice their English with someone they trusted. "She's always going off to events--parties, baptisms, funerals," says Guldbrandsen.

For Guldbrandsen, the personal enrichment has extended even to his 4-year-old son, who sometimes accompanies him on visits. "Zander has a rich collection of friends from different cultures,” says Guldbrandsen. “Along with being rewarding professionally, this project has been wonderful for my family.”

The researchers, who find their subjects primarily through word of mouth and introductions, have intentionally included many different countries of origin in their study: Sudan, Vietnam, the Congo, Bosnia, Russia, India. By not limiting their focus, the UNH team is able to show that the experience of transnationalism cuts across cultures.

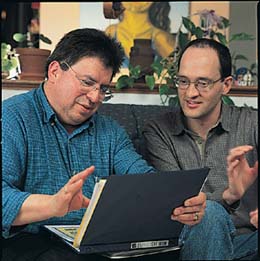

An architect by training in Columbia, Alejandro Coconubo, left, now works as a nurse in Manchester, N.H. He and Peter Buchanan '02, former UNH immigration research project coordinator, look over a sketchbook.

An architect by training in Columbia, Alejandro Coconubo, left, now works as a nurse in Manchester, N.H. He and Peter Buchanan '02, former UNH immigration research project coordinator, look over a sketchbook.

|

The current study, which provides a comparative look at two smaller cities (Manchester, N.H., and Halle, Germany), is part of a much longer-term vision, according to Glick Schiller. “I think we’re starting early enough in the process that we can establish a baseline and watch the cities and the immigrant populations grow into each other and change over time. Thad and I probably won’t be the ones working on this 30 years from now, but we can say we were there when it first started.”

As a city built on the labor of immigrants who found work in the textile mills during the 19th century, Manchester is an ideal site for the UNH study. Today the city is home to about 8,000 immigrants (about four per cent of the metropolitan area’s population), who are once again a source of economic growth as they labor in low-tech, low-wage jobs from meat-packing to axle making.

Along with a generally enthusiastic reception, Manchester provides immigrants with a critical advantage not often found in larger cities: accessibility. “We know immigrants who know the mayor and the past mayor,” says Glick Schiller. “You have easier access to many different levels of officials.” Something else happens in a smaller city. “We’ve seen it a lot, both here and in Halle,” says Glick Schiller. “Some local person: a neighbor, a worker, an elderly person, makes friends with the new immigrants, adopts them and helps them out. When you come into a whole new world, this is something you desperately need.”

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 Next >

Easy to print version