|

|

| current issue |  | past issues |  | send a letter/news |  | address update |  | advertise |  | about us |  | alumni home |

On Ben's Farm

|

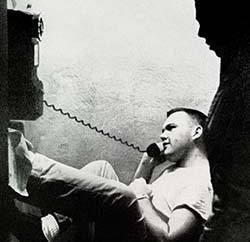

It's For You

Shared hall phones in dorms raised the question: Who will answer the phone? By Mylinda Woodward '97 |

Easy to print version |

University Archives |

You probably have the distinction of making the greatest single contribution to the jangling distraction of this noisiest of worlds," a tongue-in-cheek President Ted Lewis told Thomas A. Watson at Commencement in 1930. About to receive an honorary doctorate for his role in the invention of the telephone, Watson was best known for being on the other end of the line when Alexander Graham Bell spoke the famous words, "Mr. Watson, come here! I want to see you!"

The "jangling distraction" Lewis was referring to was the Morse-code-like series of long and short rings that UNH switchboard operators used to put calls through to buildings and dorms. When the phone rang—or, rather, when all the phones rang at the same time—everyone had to listen carefully. (Woe to all if no one answered!) Of course, anyone who picked up could listen in on the conversation. Eavesdropping opportunities abounded.

Twenty-six years later, the university installed its own phone network, with dial phones in each office and a switchboard in Thompson Hall. The party line was now a thing of the past, but in the dorms, a common phone in the hallway raised a new issue—who was going to answer the phone?

University Archives |

The women had an answer: underclassmen. (What system the men devised is unknown.) In the 1950s and '60s, phone duty in women's dorms was one of the downsides of being a freshman or sophomore. It was a serious job. While on duty, students were required to wear skirts, and smoking and male visitors were forbidden. The actual task, as described in the 1965 Freshman Handbook, was "answering the phone, taking down messages, and helping male callers buzz their dates."

The switchboard in T-Hall provided a job opportunity for students, especially on nights and weekends. The deadline for calls in the dorms was midnight on Fridays and Saturdays, and naturally there was always a flurry of calls just before the witching hour. Bill Pearce '67, who worked as a night operator, noted at the time, "Some people will do anything to get a call through ...The girls' excuse is 'I've just got to talk to him' and she spends three hours telling me why she has to talk to him. Boys pretend to be parents."

Lottie Davis, a UNH telephone operator from 1978-95, accumulated a large collection of stories over the years. One of her favorites was the call from an outside operator who had a caller on the line asking for the "Love Nest." Davis knew UNH well, but this one had her stumped. She asked the operator to repeat herself, at which point the caller, waiting to be connected, broke in and said, "No, I said I was trying to reach the 'Alumnus,'" the name of the alumni magazine at that time.

University Archives |

The number of phones on campus steadily increased. In 1961, UNH had 319 phones; by 1967, there were 1,048, which amounted to one phone for every 50 students, plus 84 pay phones. New dorms—including Devine, Hubbard and Babcock—were wired so students could plug in dial phones brought from home.

In 2010, students in a marketing research class conducted a survey and estimated that 99 percent of students at UNH owned a cell phone. While the "jangling distraction" is still with us—as classroom admonitions to "Please silence your phone" attest—the university that made Mr. Watson an honorary alumnus in 1930 decided to retire landlines in dorm rooms 81 years later. ~

blog comments powered by Disqus