|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

High-Altitdue RescuePage 3 of 4

The "dungeon" underneath the Lakes of the Clouds Hut is not for those with weak stomachs. It literally serves as a giant outhouse from Columbus Day to Memorial Day. The hut is boarded up tight, but the dungeon is left wide open to suffer the indignities of passing hikers. Most slights come in the form of human waste. For two days and two nights, this rank, dirty room served as a life-saving shelter for Timothy Speicher.

|

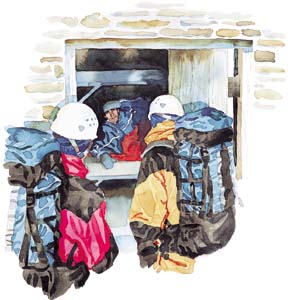

"It was a really fun hike; foggy, but not so bad that we couldn't see the cairns, about six degrees with 30 mph winds," says Chase. "We headed down to the hut, and when we got there, lo and behold, there he was."

Speicher was dehydrated and malnourished, but fairly coherent when Chase and Chesson found him. He had lost his lighter, which prevented him from melting snow to drink. "He just said, 'Good to see you guys,'" Chase recalls. "On the first night, he had actually dug a snow shelter for protection. But during the night the snow shelter collapsed, and he had to dig himself out. He somehow found his way to the hut and spent the rest of the night there. He spent the whole day and next night there, too."

Chesson says he felt a sense of relief that Speicher was now accounted for, and no one else would be put at risk looking for him. At the same time, "I'm thinking, 'What are we going to do now?' It's just starting to get windier, the temperatures are dropping, visibility is dropping—everything is screaming 'Get off the mountain,'" he says.

The first option for the rescuers, they say, was to bring Speicher back to the observatory, a hike that typically takes between 45 minutes and an hour. But Speicher was inflexible—he wasn't going back above treeline. After discussions with Fish and Game and observatory officials, a second option was agreed on—the three would descend along the Ammonoosuc Ravine Trail, the "path of least resistance," says Chase. The three-mile trail is the most direct route to the Base Road. It is usually the preferred route in bad weather, since it is protected by tree cover, though the trail also features steep, rocky sections that can exhaust the fittest hiker. But with evergreen branches buckling under the weight of fresh snow, the trail appeared more a mirage than an exit.

"We decided to follow the river, because there were no trees," says Chesson. "Here we were, going over frozen waterfalls. It was just beautiful out. If it wasn't so dangerous, we would have been having a blast."

Progress was slow. No one had snowshoes. Speicher's initial exuberance started to fade. Chase and Chesson began to worry about the alarming frequency with which the trail eluded them. Shortly after one sharp drop, Chase and Chesson punched through thin ice. In addition to fighting exhaustion and the elements, they were now wet. The cold attacked the damp clothes and boots with a shivering intensity. Chase and Speicher brooked the subject of preparing to bunk down for the night in a snow cave. Chesson wouldn't even entertain the thought.

"I said, 'No way, no way am I going to spend the night. We have to get warm and dry as soon as possible,'" he recalls.

So he and Chase plotted what they thought was the most direct route back to the trail—a 45-degree slope littered with scrub spruce—and the three began the arduous task of clawing their way up the incline. "It felt like hours," says Chesson. "What kept me going? Not wanting to be on the death list. I said, 'I'm not going to be Number 125.'"

Roughly an hour later, under clearing skies, the group burst out onto the trail above Gem Pool. "It was amazing, like a super highway—wide, open, no trees," says Chesson. Chase says he could see the lights of Bretton Woods ski area.

"Finding the trail was very uplifting," says Chase. "I'll never forget the feeling of relief, knowing this wouldn't be a disaster, we're going to get this guy out. Tim's energy level tripled, quadrupled. He was really psyched."

Chesson, however, had given his best effort to find the trail, and was starting to show signs of hypothermia. "That was worrisome, but we kept him moving," says Chase. "We radioed the summit—in the ravine we had been out of radio contact because of the topography—and Jack Halpin, who had been glued to the radio this whole time, waiting for us to call, said he was glad to hear from us. Jack told us to expect to see Fish and Game personnel soon, and that was a relief. We saw them after another mile and a half. One guy, waiting, with supplies. We were completed zonked. Dan was not even running on fumes. My feet were completely numb, like they were asleep. We were just exhausted.

"At this point, it was midnight. It was New Year's, and we could care less."

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 4 Next >Easy to print version