|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Beyond the Next HorizonThe most ambitious fund-raising campaign ever undertaken by UNH is changing the university in ways large and small

by Anne Downey '95G

On the last day of June 2002, The UNH Foundation closed the books on The Next Horizon: the campaign for the Univeristy of New Hampshire. By all measures, the fund-raising campaign was an astounding success, surpassing its $100 million goal two years ahead of schedule.

It doesn't happen like this," says Young Dawkins, president of the foundation. "I have never seen a campaign work so accurately, so quickly--almost nothing went wrong." Dawkins, who came to UNH in September 1997 from Oberlin College, where he was vice president for development, alumni affairs and communications, has spent 25 years raising money for institutions of higher learning.

"The success of this campaign says an awful lot about the generous spirit and depth of commitment that everyone involved with this university has," Dawkins notes. "And it says a lot about our potential. It has positioned us for the future. When we do it again--and we will do it again--we'll reach an even larger target."

Dawkins cites four key factors in the campaign's success. "First, (former) President Joan Leitzel's leadership was crucial. Second, there was an incredible amount of coordination and effective dialogue between the academic community and the fund-raising community, at a level that I think is new to the university. We forged a partnership that was extraordinarily effective."

The third factor was the connection that was made between the many people who care about the university and the place itself. "There were thousands of heroes," Dawkins says, "and I think people feel a sense of pride and participation that they might not have felt before. The campaign provided the opportunity and the access."

Finally, Dawkins says, the foundation's board of directors provided phenomenal support, both emotional and financial. "Current and past board members contributed more than $44 million to this effort," Dawkins says. "That is leadership."

The Next Horizon's four goals were clearly stated from the start: to enhance support for faculty; to provide additional support for specific academic programs that have already achieved national recognition for excellence; to fund new "tools for learning," such as technology, equipment and library acquisitions; and to improve opportunities for students through additional scholarships and graduate fellowships, increased funding for the honors programs and more student-research opportunities.

The stories told here illustrate how the university has been strengthened in each of the areas targeted by the campaign.

Support for Students: The World is their Classroom

Rebecca Griffin '02 knows something about new horizons, having spent much of last year researching slavery in Sudan and most of this past summer studying Gypsies in Italy.

Griffin, who compiled a 3.9 grade-point average, has uncommonly broad academic interests. She graduated with a double major in Italian and music and minors in political science and in race, culture and power. Such a varied mind thrives on independent study and research, and Griffin has seized every opportunity that has been offered to her. Happily, there have been a lot of opportunities.

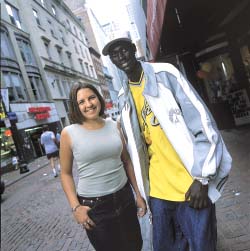

Campaign gifts enabled Rebecca Griffin '02 to conduct undergraduate research, studying modern-day slavery. She is pictured with former Sudanese slave Francis Bok. Photo by Perry Smith / UNH Photographic Services |

As a junior, Griffin's interest in human rights law led her to the Boston-based American Anti-Slavery Group, which is trying to abolish chattel slavery in Sudan. She spent a summer as an intern with the group and became so immersed in the work that she chose to write her senior honors thesis on the subject. A grant from the Rogers Family Undergraduate Research Fund, which was established through the campaign, allowed her to continue her research into the fall.

But Griffin didn't stop there. Back on campus, she started an organization called UNH Students Against Slavery in order to share what she had learned. She arranged for Francis Bok, a former Sudanese slave, to come to campus. "I realized that I could talk about modern-day slavery all day, and I wouldn't make anywhere near the impact he made in half an hour," she says.

After graduating in May, Griffin traveled to Ascoli Piceno, Italy, with the help of a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship to study the problem of discrimination against Gypsies. "It is a huge human rights issue," she says, "and there is virtually no legislation that protects them."

Griffin is one of hundreds of UNH students who have benefited from the campaign. It raised almost $28 million for the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP), scholarships, study-abroad opportunities and graduate fellowships. Griffin's UROP grant was one of 43 made possible by gifts to the campaign.

Support for Academic Programs: Leading the Way in Genomic Research

Kelley Thomas came to UNH on a cloudy day in January 2002, but his vision for the Hubbard Center for Genome Studies couldn't have been clearer. "Our mission is to focus on environmental genomics, or understanding the interactions of organisms and their environments on a molecular level," he says.

Thomas is co-director of the new center, which was created last year as a result of gifts from the Hubbard family of Walpole, N.H. It is an excellent example of the power of private support to leverage public funding. In its first year of operation, it has received $3 million in grants from the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health.

Genomics, a relatively new area of biology, involves the study of complete genomes. In other words, researchers look at the whole package of genes that make up a particular organism. "In environmental genomics, we look at the protein expression patterns of genes and how they change when a condition in the environment changes," Thomas says.

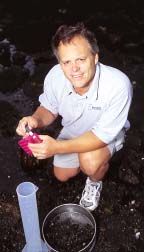

Kelley Thomas collects nematodes in a Rye, N.H., tidal pool. Thomas is the co-director of the Hubbard Center for Genome Studies. The center demonstrates the power of private gifts to leverage public support. In its first year, the center attracted $3 million in government funding. Photo by George Barker |

Little is known about the natural behavior of most organisms whose genomes have been mapped, Thomas notes. He and the Hubbard Center's other co-director, Thomas Kocher, a professor of zoology and genetics, received a grant of $500,000 this summer to assist with a project that will map the genome of several organisms whose behavior has been widely studied. "We want to understand how these organisms are interacting with their environments at the molecular and cellular levels," Thomas says. The center's role will be to develop a Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) library that will provide researchers with the genetic material they need for their studies.

Thomas's own research focuses on nematodes, or roundworms. They are the most abundant and genetically diverse multicellular animals on the planet, thriving in environments ranging from the deep ocean to arid deserts. Thomas has received $2.47 million from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to expand his research. He will lead a team of more than 40 scientists from around the world in an effort to develop a database of genetic and other biological information and to investigate molecular and cellular changes in nematodes in response to changes in the environment.

Thomas believes that the next major project in the science community will be a taxonomic survey, on a very large scale, of biological diversity--basically mapping everything that's out there. "This is a project on the scale of mapping the human genome," he says. "The Hubbard Center makes it possible for UNH to play an important role in one of the great scientific projects of the century." The Hubbard Center is one of four new interdisciplinary centers of academic excellence at UNH. The others are the Carsey Center for Effective Families and Communities, the Hamel Center for the Management of Technology and Innovation, and the Joan and James Leitzel Center for Mathematics, Science and Engineering Education. The Next Horizon campaign raised $29 million to provide a permanent source of funding for these and other key academic programs where faculty members were already collaborating across disciplines.

Support for Faculty: The Economics of Health Care

One of the first things Bob Woodward did when he arrived on campus in the fall of 2001 was to start a Health Economics Research Club. He sent an e-mail note to sophomores who had demonstrated an interest in health management, inviting them to a meeting. "I told them I'd provide the pizza and explained that I'd be giving them challenging problems to solve," Woodward remembers. "I said that I'd split $200 among the people who successfully solved the problems." Two of the students who participated in the club served as Woodward's research assistants this past summer, collecting and crunching data on the cost of hyperlipidemia, or high cholesterol, in patients who have had a kidney transplant. It was an invaluable experience for them, he says. "Any student who can take a data set, do analyses and then write up the results is pretty much guaranteed a job."

Woodward holds the Forrest D. McKerley Chair in Health Economics, one of four new distinguished chairs created at UNH during the campaign (the others are chairs in space science, developmental psychology and genomics). Gifts also created professorships in four different areas and provided funds for visiting professors, distinguished lecturers and the Teaching Excellence Program, which helps faculty members to develop courses and improve teaching methods.

Bob Woodward holds the Forrest McKerley Chair in Health Economics, one of four distinguised chairs created during the campaign. The others are in space science, developmental psychology and genomics. Photo by Doug Prince / UNH Photographic Services |

Woodward thinks of himself as a bridge between the Whittemore School of Business and Economics and the School of Health and Human Services. Each year he teaches an undergraduate course that is offered by both schools and a graduate class in each. His research also bridges the fields of economics and health care. He's currently studying the socio-economic determinants of kidney-graft survival, supported by a $411,632 grant from the National Institutes of Health.

"In the early 1980s, Congress voted to pay for a kidney transplant for anyone whose kidneys failed," Woodward explains. "It was the first step toward national health-care insurance. But there was a technical problem: they only paid for immuno-suppression medications for a year after the surgery. Kidney-transplant patients need to be on that medication for the rest of their lives, and it costs between $10,000 and $12,000 per year."

In 1993 Woodward's analyses of kidney-graft recipients proved that the survival rate of rich and poor patients was the same for a year after the operation. But in subsequent years, the graft-failure rate was 50 percent more for poor people. As a result, Congress voted to cover patients for three years after the operation, four years if the patient is over 65. Woodward is currently analyzing the data on kidney grafts and race.

"When you have an endowed chair to fill, you look for someone who is active in major, nationally funded research projects, who has a national reputation," says Jim McCarthy, dean of the School of Health and Human Services. For Bob to win a very competitive, multi-year NIH grant in his first year at UNH speaks to the excellence of his work and the excellence of our choice."

Learning Tools: The Heart of an Urban Campus

You can't help but think about what was going on here 100 years ago," says Cindy Tremblay '91, an associate in the newly renovated UNH Manchester library. Standing in what was once a factory building in Manchester's historic mill yard, she points out the high brick walls, the wooden beams, the granite coal chute and an enlarged sepia photograph of men working on a fire engine.

At the turn of the last century, this was the boiler room for the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company's machine shop, where workers made textile- and shoe-making machines, sewing machines, steam locomotives, fire engines and Civil War muskets. These days, the old boiler room is filled with stacks of books, computers that are fully compatible with Dimond Library's databases and online catalogue, and seating for more than 100 people.

The campaign raised $3.3 million for "tools of learning," including library resources for the campuses in Durham and Manchester. The photo above was taken in UNH-Manchester's new state-of-the-art library in a renovated mill building. Photo by Gary Samson |

The boiler room is just part of the new library, which at 9,300 square feet is three times the size of the former UNH-Manchester library in French Hall, seven miles from downtown Manchester. In 1999, the University sold French Hall and 860 acres of land to the City of Manchester and bought the mill building, consolidating its Manchester campus downtown at the mill yard. The library renovation was supported by the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Next Horizon Campaign, and the work was completed in the fall of 2000.

The campaign raised $3.3 million for the Manchester library, Dimond Library and other "tools for learning." The goal was to make sure that students and faculty members have the printed and digital materials they need to get the most complete and up-to-date information in their fields and to add to that information through their own research.

The new library in the mill yard houses 120,000 volumes, six times the number in the old library. It has become a repository for special collections emphasizing local and regional history and a location for displays relating to the history of the mill yard and events of interest in the city. A community resource room has made it possible to host book-discussion groups that are open to the public and to offer sessions on local history for students in grades K-12 and their teachers.

"The renovation has pumped new life into this community," says Ginger Lever, director of college relations and enrollment management at UNH-Manchester. Cindy Tremblay agrees. "In the old library, we never saw half the student population. In our first year here, our foot traffic increased over 200 per cent. Now we really feel like we're getting to know the students."~

Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus