|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Alumni Profiles

Where Conductors Can Let Their Hair Downby Erika Mantz

|

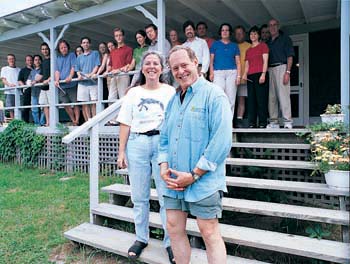

| The tuxedos are left at home: Ken Kiesler '75, right, runs a summer retreat for conductors at Maine's Medomak Camp. Owner Holly Gudelsky Stone '77 is at left. |

If your idea of a symphony conductor is a tyrant in a tuxedo waving a thin wand in front of a group of musicians, you're not alone. And you're also not 100 percent right.

Oh sure, many of those things are true--formal dress is the norm, the baton is a constant and conducting is primarily a male-dominated field--but "conductor" is no longer synonymous with "tyrant." It's a kinder, more gentle profession.

"Our philosophy today is that everyone in the orchestra is a colleague," says Ken Kiesler '75, music director of the New Hampshire Symphony Orchestra. "A conductor is a leader among peers, and has to be a good person as well as a good musician. The people in your orchestra are not workers, they're artists, and every member has to feel valued."

But ultimately, the conductor is still in charge, and still the one responsible for providing a quality musical experience for the audience. The bottom line is that any mistakes are attributed to the conductor, and the podium out in front of the orchestra can be a lonely place when things go awry.

So when Kiesler, who is an internationally known conductor and head of the country's number one graduate conducting program at the University of Michigan, wanted to provide an opportunity for conductors to let down their guard a bit, shake off the leadership mantle and try new things in a safe environment, he remembered Medomak Camp in the small Maine town of Washington where he spent summers as a boy.

"We could hold the retreat at a university or conference center, but it wouldn't be the same," Kiesler says. Instead, he turned to the summer camp he credits with molding his principles and values as a man, which include both an emphasis on personal achievement and consideration for others. The retreat is more than a place for conductors to hone their skills, it's a place for rejuvenation and renewal.

"We wanted a place for people to feel safe," he says. "Conductors are always the leader, but at camp they don't stand out; they can be part of a group and learn from each other. An instrumentalist can stay behind the doors of a practice room until a piece is perfect, but if a conductor is going to make a mistake, it will be in front of hundreds of people."

So what do conductors do at camp? They shed the tuxedos, for one. Dress is casual and there are activities from early morning until the last embers of the campfire die out. There's also 17 days of spartan cabins, family-style meals and searching the night sky for constellations.

But conductors' camp is not a vacation, Kiesler stresses: "Here they pretty much practice and study 24 hours a day." That includes score reading, which is developing a sense of what the piece should sound like; aural skills, which is training the ear to hear harmony, melody and the emotional content of a note; and body movement. "Good conductors spend 90 percent of their time studying and thinking," Kiesler says. Every 10 minutes, all day long, someone takes over the baton and practices conducting.

Camp is not all work, however. Kiesler, who is a trained Maine Guide himself, makes sure everyone has several hours a day of individual time to walk in the woods, kayak on the lake or just meditate.

"I believe the Medomak philosophy can benefit the world of music in general and conductors in particular," he says. "We're dealing with the whole person, a certain way of being for a conductor, not just how to do it."

Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus