|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

The Species RaceThe world is losing plants faster than scientists can find them

By Virginia Stuart '75, '80G

Photography by Lisa Nugent

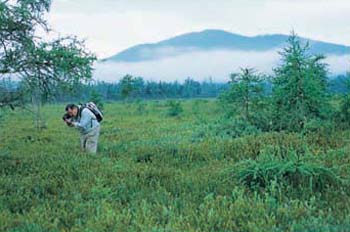

Garrett Crow, the chair of the plant biology department, is a botanist-of-the-world in the mold of the great taxonomists of the past. He has "botanized" in places like Tierra Del Fuego, Bolivia, Siberia, Labrador and the Amazon. He has waded waist-deep into tropical waters, studying giant water lilies with leaves the size of small trampolines, climbed to alpine meadows in the Crimea where the wild cousins of tulips and peonies grow and marveled at carnivorous bladderworts growing in the trees of the Costa Rican cloud forest. He dismisses as mere annoyances the mythic-sounding trials he has endured, from blood-sucking leeches to the scrutiny of the KGB. Wherever he goes, he gathers plant specimens in a temporary field press of newspaper and cardboard, and like Darwin and so many other naturalists before him, he describes the plants and habitats in his journal.

Garrett Crow adds to his collection of nearly 40,000 slides.

Garrett Crow adds to his collection of nearly 40,000 slides.

|

An internationally known expert on aquatic plants, Crow is co-author (with C. Barre Hellquist '65, '66G) of the definitive book on aquatic plants in northeastern North America and author of a similar book on aquatic plants in Costa Rica. In 1993, he published an article on a surprising discovery he made when comparing aquatic environments in Costa Rica and New England. He found that, contrary to the pattern among terrestrial plants, New England's aquatic environments are as diverse as those in tropical Costa Rica--or more so. Subsequent work with then-doctoral student Nur Ritter '92, '00G in Bolivia and a recent trip to the Amazon revealed a similar pattern. A solid, patient man who takes the long view, Crow suspects the retreat of glaciers from northeastern North America more than 13,000 years ago contributed to our diversity in aquatic plants by leaving behind so many different types of aquatic environments.

Crow believes his discovery emphasizes the need to "preserve what we have." He and his students have advised consultants on ways to enhance diversity of created wetlands and avoid the introduction of non-native species.

Preserved plant specimens, and the standardized Latin names used to identify them, allow botanists like Crow to make comparisons across geographic borders--or across time periods. Art Mathieson has, in effect, collaborated with a Victorian botanist named Frank Collins, who died in 1920.

A self-taught but scholarly amateur from Massachusetts, Collins made an extensive seaweed collection that has enabled Mathieson to compare the flora in Maine harbors then and now. The 77,000 specimens Mathieson has collected over 30 years at 1,000 sites in New England will, in turn, present an important historical record for future ecologists. Since today's botanists have analyzed the DNA from fragments of specimens collected 200 years ago, Mathieson knows his collection could be used in ways he can't even imagine today. Even a simple list of the plants growing in an area in the past can make all the difference in efforts to restore the habitat for an endangered species--like the masked bobwhite quail successfully reintroduced in Arizona.

In this corner--the botanists

Writing in the journal Science in 1997, James Blackburn, head of the United Kingdom Society of Systematists, estimated that there were only 7,000 biological taxonomists in the world, a number he termed "clearly inadequate." The National Science Foundation, also recognizing the loss of taxonomists at a time when they are most needed, has established a program to encourage the training of new taxonomists.

The number of taxonomists has been dwindling for several reasons. Many, like Art Mathieson and Garrett Crow, are nearing retirement age, and few young faculty members are coming into the field. Crow explains why taxonomists are underappreciated: "We're detail people, we make collections and we make students memorize." Take Janet Sullivan, for example. An adjunct professor of botany and editor of the journal Rhodora, she teaches the UNH course in plant systematics: taxonomy with an emphasis on evolutionary relationships. She estimates that students in her course must memorize 350 terms used in plant identification plus the Latin names of about 150 plant families and genera, as well as some terms from related fields like molecular biology.

Bog plants of interest include the pitcher plant, Sarracenia purpurea, which devours insects and even the occasional frog; an orchid, rose pogonia, Pogonia ophioglossoides, center, and a blue flag iris, Iris versicolor, right.

Bog plants of interest include the pitcher plant, Sarracenia purpurea, which devours insects and even the occasional frog; an orchid, rose pogonia, Pogonia ophioglossoides, center, and a blue flag iris, Iris versicolor, right.

|

Easy to print version

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 4 Next >