|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

GiftedWho would give away their most precious piece of art?

By Suki Casanave '86G

Photography by Lisa Nugent

THE ART ENTHUSIASTS on these pages have discovered a secret: that the greatest satisfaction lies not in how much you can accumulate, but in what you can give away. "Collecting," says Cecil Schneer, retired professor of geology, "can be a self-defeating undertaking. You become interested simply in possession and lose sight of the usefulness of the thing itself." The donors here, whose gifts of art have enriched the UNH Art Gallery, have different backgrounds and tastes, but they share a passion for "the thing itself." They share a commitment to art that is used, art that is seen and appreciated, art whose purpose lives on. "I think you can come out a lot happier if you donate your work of art instead of selling it," says Schneer. Beyond a generosity of spirit, becoming a donor requires a certain inner fortitude, a willingness to say good-bye to treasures that have been lived with and cherished for many years. "Donors must be able to face the fact that they are releasing something of great value to them," says Vicki Wright, director of the gallery. The university's collection has grown through the years thanks to those whose portraits grace these pages, and others like them—lovers of art who have learned to let go, who have discovered the art of giving. (Visit the UNH Art Gallery website to learn more about UNH's collection and the donors who have made it possible.)

|

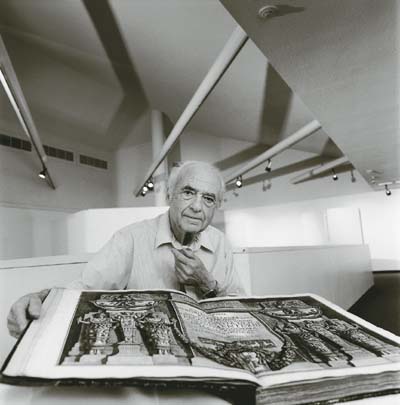

"Open this book, which is several hundred years old, and you're almost afraid to touch it for fear the ink is still wet," says Cecil Schneer. "The lines are so crisp, it looks like it was made yesterday." A retired professor of geology, Schneer also has a passion for art, which he shared with his late wife, Mary Barsam Schneer '61, a devoted Art Gallery docent. They found this rare bound volume by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, one of the premier printmakers of the 18th century, during one of their sojourns in Europe, and Cecil gave it to UNH in memory of Mary. "We were not collectors," says Schneer. "We just accumulated a few things that had meaning to us."

-Maryanna Hatch |

For nearly four decades, John Hatch encouraged generations of UNH art students to develop their talents. The walls of his home were filled with the works of students, many of whom became artists themselves. After his death, his wife Maryanna (holding "Perch" by Gerald "Jerry" MacMichael '65) took the paintings and prints off the walls and donated many of them to the university, a gesture designed to continue her husband's legacy. Gallery director Vicki Wright regularly brings works of art, including those of Hatch and his students, into classrooms for up-close study and appreciation. "We are a teaching museum," she says. "Art as a tool for learning is a vital part of our mission." John Hatch would be pleased.

-Sigmund Abeles |

Sigmund Abeles was in his New York City apartment on Sept. 11, 2001, when the planes hit the twin towers of the World Trade Center. The chaos that ensued was eerily familiar, reminiscent of a time during the Vietnam War nearly four decades earlier which the artist had depicted in a print. "The atmosphere in that print is very similar to the atmosphere in the city that day," says Abeles, who taught art at UNH for nearly two decades. Created from news photographs, "Gift of America" portrays the delivery of the deadly "gift" of napalm. One of these limited-edition prints resides in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. Another belongs to the UNH Art Gallery. "The gallery is such a wonderful resource," says Abeles. "It's a place where students can see the texture of the paper, the quality of the mark." And it's a place where they can see how another artist, in another time, used his art to respond, to make a statement about world events.

Page: 1 2 Next >Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus