|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

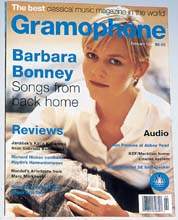

Nobody's DivaOpera is fun, says Barbara Bonney '78, '00H. It's golf that's hard.

By Jane Harrigan

Becoming one of the world's leading sopranos is really quite simple, Barbara Bonney '78, '00H is explaining. First you leave UNH to spend your junior year in Salzburg, Austria, mostly because you love "The Sound of Music." You're a cellist, but you don't bring your cello because you can't afford to pay the freight.

by Johannes Ifkovits |

Without the cello, you have more time for singing. A teacher in Salzburg sets up an audition at an opera company in Germany, so you try out. The job offer is a compliment, and you need the money, so you take it. Poof. You're an opera singer. You sing 40 roles in Darmstadt in four years, learning as you go, and then other offers start coming in. Next thing you know, it's 1984 and you're 28 years old. You're onstage at Covent Garden in London for the first time, awaiting your cue in a Strauss opera. Nervously, your eyes focus past the audience on one particular green Exit sign, and you think, "How did this happen?"

Barbara Bonney inhabits a world of gilded concert halls and international acclaim. Yet in her mind she's still a kid from Maine with a lobster license, a teenager putting herself through UNH by waitressing and teaching calligraphy. Onstage at Theatre Musical de Paris Chatelet, her perfectly styled hair gleams blond, her black gown glimmers with silver beads. Hands clasped before her as if ready to receive communion, she delivers Scandinavian art songs in a lyric soprano so pure that the audience barely dares breathe. Bonney looks so much at home among the cultural elite that J.R.*, a friend from UNH days, can't help feeling a little awestruck.

Yet Bonney is also so down-to-earth as to be, in J.R.'s words, "downright earthy." She speaks of the most rarefied topics in the most matter-of-fact way. Though she loves and champions early music performed on authentic instruments, she jokingly calls it "vegetarian music." When she proudly proclaims that she's acted in 65 operas without ever taking an acting lesson, she hoots: "They teach you how to sit in a chair and sing at the same time! Good God!" The earthy laugh is one reason that, on the rare occasions when they get together, J.R. still recognizes the girl she saw one '70s morning on the Bonney family farm in Maine. That Barbara Bonney was standing in the snow feeding the ducks—dressed not in beads but in Bean boots and a red union suit.

|

The route from the farm to the world's great stages was nowhere near mapped out when Bonney attended UNH, but her journey makes perfect sense to people who knew her then. "She wasn't somebody you had to do much to teach," says retired music professor Keith Polk, who directed Collegium Musicum and Canzona, two UNH groups in which Bonney sang. "Basically you'd just stand back and let it happen." Bonney never mentions that she has perfect pitch—the first thing other musicians remark upon when they talk about her. Neither does she dwell on the lean years in Europe. Friends, however, remember tales Bonney used to send in thin blue aerograms—stories of living in attic flats with no bathrooms, scrounging for food, singing every night with no time off and working odd day jobs to survive. Those years taught Bonney not just discipline but the artist's biggest secret: the effort it takes to look effortless.

Page: 1 2 3 Next >

Easy to print version