|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Naked AmbitionIt's not just the 21st century that has Olympic fever -- the ancient world was sports-crazed, too.

by Suki Casanave '86G

Photo by Myron/Corbis

Photo by Myron/Corbis

On a raw October day, mud is flying on a fallow field in southern Spain. Four teams of horses gallop around a crude track, hooves digging into the rain-soaked earth, desperate for traction. Behind each pair, a driver strains to maintain control in a tiny, open two-wheeled chariot. Legs braced, reins in hand, the charioteers lean into each turn and hunch forward on the straight-a-way. Crowds cheer. Spectators jump to their feet. No one leaps onto the race track, though. No one casts himself, in a fit of passion, directly into the path of the speeding chariots.

This is, after all, a documentary, not the sports-crazed world of ancient Greece and Rome where such displays of zealous enthusiasm were almost common. Staged by the BBC, this 2002 re-creation of a once-popular spectator sport is accurate in every detail, right down to the wooden spokes of the chariot wheels, with one exception: the modern-day spectators opt only for cheering, leaving the track to the charioteers.

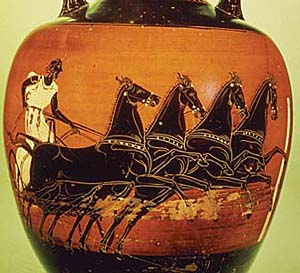

Competitor in chariot rase, Greek vase, 5th century B.C. Courtesy Bridgeman Art Library |

"The producers were historically minded enough to get the details right," says Stephen Brunet, a UNH assistant professor of classics who has consulted on a number of films, including this one. A leading expert on ancient sports, Brunet is currently assisting with the production on a Canadian film scheduled to be released later this year in conjunction with the upcoming Olympic games. He has even taken a turn in front of the camera in a Learning Channel version of the BBC documentary, shot mainly at the California Speedway in Los Angeles.

"We Americans, and the Romans, are the only ones in history who have devoted so much time, effort and money to racing around an oval race track again and again," says Brunet, shouting to be heard on camera above the revving engines behind him. He is right down in the pits, next to the cars, comparing the Circus Maximus racetrack of ancient times with the speedway of today.

Brunet knows an awful lot about sports for a guy who, well, hates sports. To be accurate, what he dislikes is watching modern sports; what he loves is studying ancient ones--and trying to figure out what the Greek and Roman passion for sports can teach us about another place and time. "I'm looking for clues," he says, "that suggest the values and the attitudes of a society."

Ancient chariot races, for example, celebrated speed and danger. They were punctuated with spectacular crashes; always lurking was the possibility of death. Competitors were revered for their skill and courage--all for the sake of winning a race. "The ancient Greeks had no notion of just playing for the sake of competing," Brunet says. "There was no second or third place. Winning for them was everything."

Hero Worship

Milo of Kroton is a guy who could give even the best modern Olympic athlete an inferiority complex. The six-time Olympic wrestler competed--and won--for a quarter century, a record of longevity unheard of today. His feats of strength became the stuff of legend. One account tells of how he liked to impress admirers by tying a cord around his forehead and then, holding his breath, straining until he broke the cord with his bulging forehead veins. In another display of superhero talents, Milo gallantly saved a throng of people by supporting the central pillar of a collapsing building until everyone had fled to safety.

Stephen Brunet, UNH assistant professor of classics, carries a torch

for ancient sports.

Photo by Perry Smith

Stephen Brunet, UNH assistant professor of classics, carries a torch

for ancient sports.

Photo by Perry Smith

|

Olympic victors like Milo, who went on to achieve hero status, typically got their start in one of the thousands of regional athletic competitions that were held throughout the Greek world and, later, the Roman Empire. Athletes who achieved local success went on to participate in the most famous of ancient games, the Olympics, which had an incredible 11-century run until they were abolished by Byzantine Emperor Theodosius I in about A.D. 393. The modern Olympics, modeled after these early games, began in 1896 and will celebrate its 100th anniversary this year. (The games were canceled during the world wars.)

In the ancient world, rewards for winning an Olympic first place were relatively simple, involving fame, rather than fortune. The Greeks honored victors like Milo with an olive wreath--and long-lived celebrity. Memorial statues included descriptions of an athlete's accomplishments, a sort of resume in stone. "The Greeks were nuts about writing on stone," says Brunet, who has studied hundreds of inscriptions from tombstones. "These accounts were very complete, including wins and later career moves." Athletic prowess was also immortalized in verse by poets, the journalists of the day. These poems were often committed to memory, recited, and passed down through generations, keeping alive the memory of a particular victory long after the athlete himself was gone.

One Olympic hero, Theagenes of Thasos, is best remembered for a feat he accomplished after death. Memorialized with a bronze statue, the boxer remained a source of aggravation for at least one of his rivals, who came nightly to rant at the feet of his former nemesis. One night, in a plot twist worthy of a good classical myth, the statue toppled onto the opponent and killed him. His sons, understandably outraged, filed charges against the statue for murder. (Prosecuting inanimate objects was standard practice in Greek society.) The killer statue was duly punished with drowning in the ocean. Still, Theagenes would not be defeated. Years later, during a time of severe famine, the statue was hauled out of the ocean and repositioned as a god of sacrifice to help end the famine. Here, finally, the story ends. Theagenes rules.

Some athletes chose another road to immortality--they cheated. Those who were caught were heavily fined, and the money was used to build statues of Zeus on the road to the Olympic stadium. Inscriptions on each statue detailed, for posterity, the specifics of the cheating. Eupolus of Thessaly, the earliest recorded cheater, is remembered for bribing boxers in the 98th Olympiad. Others were noted for buying off competitors or fixing the outcome of matches. "We can't tell how rampant cheating was," says Brunet, "just as we can't determine this issue precisely today, but the most spectacular cases are immortalized, and 2,000 years later, we still know about them."

Page: 1 2 Next >Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus