|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Naked AmbitionPage 2 of 2

The pursuit of excellence

Infamous exceptions aside, Greek civilization is credited with giving the world the ideal of excellence, or arete. Greek men were expected to demonstrate excellence in a number of venues: on the battlefield, in politics and in sports. "Your position in Greek society was determined by what other people thought of you," says Brunet. "It was a very, very competitive world."

The Olympic games were an opportunity to demonstrate excellence in public, not only for personal glory, but to please the gods--in this case, Zeus. As part of a major religious celebration, the games took place in the Altis, the sacred grove of Zeus, and featured the sacrifice of 100 oxen on the middle day of the festival.

Along with endless religious ceremonies, the Olympic games included a host of side shows: speeches by philosophers, poetry recitals, parades, banquets and craftsmen selling their wares. The event was also an ideal venue in which to show off. The wealthy attempted to outdo one another with lavish displays: decorated tents, expensive chariot teams, feasts and more. "It was a chance," notes Brunet, "to see and be seen."

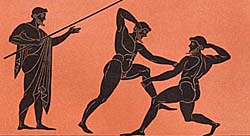

One look at an ancient vase or two confirms that the Greeks took this concept of being "seen" to its logical extreme, competing completely in the nude. There were exceptions, of course. Charioteers were fully garbed. The hoplitodromos featured competitors running at full speed clad in armor. But javelin and discus throwers, wrestlers and boxers were naked. Jumpers are depicted in mid-air, arms outstretched, sans clothing. They are, however, gripping halteres, or stone weights, in each hand to increase the length of the jump.

Even the ancient Greeks themselves couldn't explain exactly how the tradition of competing in the nude originated, though they had stories about it--including one about an athlete who lost his pants mid-race and discovered he ran faster. "More important than the question of why this practice developed," says Brunet, "is what it says about being Greek." In contrast to barbarians (literally "those who do not speak Greek"), who wore clothes and did not participate in sports, Greeks practiced athletics and were proud of their bodies. "Being nude became representative of being Greek," says Brunet. "And the Greek concept of beauty is based on what they saw in the gymnasium."

| " Pnme One look at an ancient vase confirms that the Greeks took this concept of being 'seen' to its logical extreme " |

Along with this admiration for beauty, spectators in ancient times exhibited a fascination with danger and drama--thus, the popularity of the high-speed chariot races. There was also the pankration, an event the poet Xenophanes describes as "that new and terrible contest." This grueling combination of boxing and wrestling dished up plenty of violent moments. Rules forbade biting or gouging of the eyes. But punches, kicks in the belly and broken fingers were perfectly acceptable.

Boxing lessons

It was a Roman coin in a New York museum that first caught Brunet's eye--and helped define his scholarly career. The coin bore an image of a boxer wearing gloves. "This was something I'd never seen, never read about," says Brunet, who knew he was in uncharted academic territory. "I wanted to see what could be learned from these boxing gloves."

To find answers, Brunet conducts meticulous detective work. He studies vases, sculptures and mosaics, scrutinizing each figure portrayed for any sign of boxing gloves. He also pores over written texts for chance references to gloves. Gradually, Brunet has compiled details of the boxing story, and he is considered the leading expert on a particular category of the sport--boxing dwarfs, a phenomenon that developed during the Roman Empire. These boxers were skilled athletes and took their sport seriously, says Brunet, despite the fact that the Romans hired them to entertain at dinner parties.

Wrestling match with an arbiter by Roulez, after a Greek vase painting. (C) Corbis |

Brunet recently published a scholarly article on dwarf boxing. Another paper--all 20,000 words of it--will be out shortly, based on that original Roman coin, an accomplishment that represents more than a decade of work.

"You pull all this evidence together," says Brunet, "and you attempt to make a judgment about what's true about these gloves and then, what does it represent about the Greeks? What does it say about the Romans, who were even greater fans of boxing? Were they interested in it only for the bloodshed? More likely, it was because it was fast and competitive and required stamina and willpower to withstand pain--qualities both the Greeks and Romans valued highly."

So can we blame it on the Greeks--our own sports-crazed culture, where toughing it out remains a virtue, and violence is tolerated in the name of competition? Where excellence and beauty are ultimate goals? Where victors are worshipped--and often paid--like heroes?

"Sports got overblown in the Greek world, and I think they're overplayed in our society, too," says Brunet. "While we may be reluctant today to go as far as the Greeks and say that winning is everything, the importance of winning remains paramount. And the study of ancient sports highlights that it's been an issue for a long, long time."

Still, every four years a torch is lit, athletes gather, and fans around the globe celebrate, as they did in civilizations past, incredible displays of athletic skill and grace. On this there is no debate. "Let the games begin!" ~

Page: < Prev 1 2Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus