|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Alumni Profiles

An Eye for a Good VoiceBy Suki Casanave '86G

"My name is Dovey Coe, and I reckon it don't matter if you like me or not. I'm here to lay the record straight, to let you know them folks saying I done a terrible thing are liars. I aim to prove it, too. I hated Parnell Caraway as much as the next person, but I didn't kill him."

|

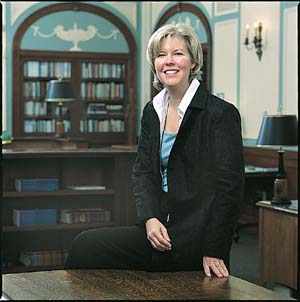

Caitlyn Dlouhy '84 knows a good voice when she hears one. And Dovey Coe is good—authentic and quirky. "I fell in love with this character from the beginning," says the children's book editor, who acquired the young adult novel Dovey Coe by Frances O'Roark Dowell for publisher Simon & Schuster. "The voice—the tomboy, feisty girl aspect—just pulled me in immediately."

Dlouhy first read those opening words as she was working her way through stacks of unread manuscripts on her notoriously messy desk. "When I believe in a book, I fight for it," says Dlouhy, who has developed her editorial ear over 15 years in the business, first with HarperCollins, now with Simon & Schuster. She works with an author through draft after draft for as long as it takes. Along the way, she goes through lots of green pens. "I never use red," says Dlouhy. It's too reminiscent, she thinks, of academia and those dreaded red margin comments.

Dlouhy (pronounced Da-lou-ee) labors over her exchanges with writers, striving to justify every suggestion, lacing her comments with encouragement even as she maintains a ruthless honesty. "My editorial letters can take days to write," she says. It was Tom Williams, the late UNH professor of English, who helped her understand the importance of a good critique. "He was honest," Dlouhy says of the fiction-writing class she took with Williams. Dlouhy pursued her dream of being a writer by enrolling as a graduate student at the University of Pittsburgh. "We spent 90 percent of our time critiquing each others' work," she says. "And finally the light bulb went off. I realized I liked editing."

Today, Dlouhy talks about the books she's edited, the ones she has nurtured from early drafts through to publication, like a proud mother describing her children's accomplishments. She loves Postcards to Father Abraham for its dense, poetic language. "If you took out one line the whole thing would fall apart," she says. Boy with a Lampshade on his Head is what she calls "a 12-Kleenex novel," managing to be funny and heartbreaking at the same time. And Newbery Medal-winner Kira-Kira, another young adult novel, leaves her astonished every time she revisits it.

Family and friends often ask Dlouhy when she's going to be promoted to editing adult books. She laughs at the question even though she once envisioned herself editing the next great American novel. But when she interviewed for her first job at HarperCollins, she wound up meeting and ultimately being hired by renowned children's book editor Laura Geringer. "I was talking about children's books with the secretary while I waited for my interview with another editor. The woman insisted I meet Laura. Told me I'd love her. Well, she was right." Dlouhy quickly learned that producing children's books—good ones—is much harder than people assume. "Everyone thinks they can write one," she says, "but finding the right voice—that's not condescending—and telling a story in a short amount of space is actually very difficult."

These days, Dlouhy can test her latest book selections on her in-house critic, daughter Grace, who at 3 is starting to offer plenty of commentary. Juggling motherhood and work is a continual challenge, Dlouhy admits, but one she's happy to take on. Nearly every day, she says, she thinks about how lucky she is to have a job she loves so much. Then she grabs a green pen and gets to work.

Easy to print versionblog comments powered by Disqus