|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

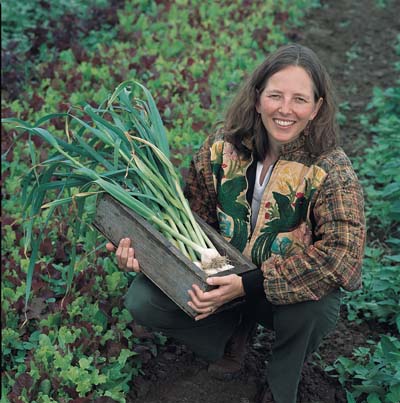

Planting HopePage 2 of 3

|

Reed launched Sustainable Harvest International in 1997 out of a bedroom office in her parents' New Hampshire home. It is, as far as she knows, the only organization in the world providing long-term technical assistance to rural families in the tropics, offering them alternatives to slash-and-burn agriculture.

The early days were not easy. Reed did everything from fund raising to filing. "I didn't really have a personal life," she says. "It was pretty much sleep, SHI, sleep, SHI." Reed was driven by a constant sense of urgency: according to some estimates, another acre of rainforest is destroyed every second. Saving the rainforest, she knew, would mean changing minds. The people living in the shadow of these forests, cutting its trees, scraping a living from its depleted soil, needed new ways to think, new ideas to try. But they had no access to information. "They don't watch TV," Reed says. "They don't read magazines or newspapers. Most have, perhaps, a third-grade education." And so Reed went to talk to them herself.

|

"In the beginning, we couldn't even afford a motorcycle," she recalls. "So we went on foot, by bike, by horse—anything we could find." Accompanied by Yovany Munguia, the first Sustainable Harvest extension agent, Reed made her way into villages often days away from the nearest city. Sometimes, during the rainy season, she battled knee-deep mud to reach her destination. "This is when it dawned on me what it means to be the director of an international nonprofit," she says, laughing. Meeting in schools, churches or community buildings, Reed spoke in Spanish to small groups of interested farmers. Her pitch was low-tech—no splashy computer presentations or photo displays. She had only her own experience with farmers in Panama to draw on. But she also had Munguia at her side—and the promise of regular return visits over the next few years to help farmers establish the new techniques.

In the farming community of Oro, Honduras, for example, Reed worked with Ramon Salguero, who used to harvest only 4,000 pounds of corn per acre from his land despite using hefty amounts of chemical fertilizers. Using sustainable methods and organic fertilizer, Salguero harvested about 10,000 pounds per acre. Don Cheyo, who also lives in Oro, once grew only beans and coffee. Five years ago, when the local Sustainable Harvest extension agent convinced Cheyo to try Tabasco peppers (as well as passion fruit and cassava) along with his traditional crops, his annual income jumped from $900 to nearly $4,000.

|

Farmers working with Sustainable Harvest learn a number of sustainable techniques—including -crop rotation, erosion control and pest management—that help them farm the same land year after year without depleting the soil. They also learn to plant agro-forestry plots, fields that mimic a natural forest with an overstory of hardwood trees high above plants like bananas, coffee and ginger, all of which thrive in the shade. This method brings with it an economic benefit, too: If the market value of one crop drops, as has been the case with coffee in recent years, other crops can help make up for the lost income.

Reed's approach took time and patience. "At first, people are scared to try something new," she says, "especially if the survival of their family may depend on it." It's not that slashing and burning an acre of rainforest is easier than farming it in a sustainable way. The traditional method is grueling and slow. But it's familiar. Reed could see, though, that her method was working. "At first, out of, say, 23 families in a village, maybe only six or seven would be interested in working with us," Reed says. "Eventually, once they saw the results, we'd have 21 or 22 of them on board." ��

|

Over the years, Sustainable Harvest International has grown along with the success of its farmers. Eventually, Reed was able to hire a part-time project manager named Bruce Maanum, an anthropology researcher she met in Belize. Today, Maanum supports Reed's work in his new role—as her husband. And the organization now has a full-time program director, as well as a development director and an outreach coordinator. Aside from these four "gringos," who manage the organization, all the other employees are local extension agents who work in Central America, returning again and again to the fields, answering questions and working with farmers—just as Reed first envisioned.

In eight years, SHI has helped more than 746 families in 76 communities convert more than 3,000 acres to sustainable agriculture. And since every acre farmed sustainably saves roughly five acres of rainforest, Reed calculates that about 15,000 acres of tropical forest have been saved. "It's still coming down faster than we can get it back up," she says. "But what we've saved is significant, and to the farmers and their families, we're making all the difference in the world," she says. One young farmer felt so moved by his transformed life that he asked Reed to be the maid of honor at his marriage.

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 Next >Easy to print version