|

|

| current issue |  | past issues |  | send a letter/news |  | address update |  | advertise |  | about us |  | alumni home |

Features

Be Still My HeartPage: < Prev 1 2 3 4 Next >

|

McAllister, who dreamt up the trip, was an accomplished technical rock and ice climber and a phenomenal kayaker who could do Eskimo rolls without a paddle. He worked summers as a ridge runner, educating hikers and maintaining trails in the White Mountain National Forest. He and another Outing Club member were among the first to make a winter ascent up Cannon Mountain's famed rock face.

Back at UNH, McAllister, Levesque, Jones and a group of club members worked in the basement of then-college president John McConnell, designing and building whitewater kayaks. The Outing Club was ahead of its time, says Jack Pare '75. Though most New England colleges were involved in down-river racing, the focus at UNH had turned to expeditionary adventures.

In early April, the group took a weeklong shakedown trip on the Saco River to test their gear and practice loading their newly fabricated 13-foot boats. The kayaks, which Pare and McAllister adapted from their down-river designs, were huskier on the bottom in order to survive bracing rock collisions and had a better defined keel for tracking across large windblown lakes.

The boats' design was advanced, but they possessed none of the safety equipment that is common today: they traveled without any communication devices or life jackets, and their boats lacked flotation. Their Department of Mines and Technical Surveys maps were based on surveys and aerial photographs conducted between 1948 and 1961. "Paddling like we did is unthinkable today," concedes Jones. Yet at the time, theirs was considered a high-tech approach—with lightweight camping gear and alpine-style techniques the original voyageurs couldn't have dreamed of.

THEY LEFT LEVESQUE'S HOUSE in Nashua, N.H., on June 7, 1968, traveling by van to Montreal, then by train to northern Alberta, jumping off at the end of the Northern Alberta Railroad four days later at the settlement of Waterways. After picking up supplies, including a .22 rifle, and shuttling to Fort McMurray, they launched on the afternoon of June 11. Jones wrote that their boats, each laden with almost 140 pounds of equipment and food, "felt like...submarines about to go down."

UNDERWAY: From left, Gardner "Chummy" Chamberlain '70, Dennis McAllister '68, Glen Levesque '70 and Geoff Jones '70. |

The team paddled 70 miles up the Clearwater River over the next eight days, struggling against a stiff current and swarms of insects. After a week, they seemed to hit their stride. McAllister had luck reeling in a record eight-pound fish, and Jones recalls the team efficiently walking their boats through towering limestone gorges and portaging around the Class IV rapids near the Alberta-Saskatchewan border.

On their first big challenge of the trip, the arduous portage out of the Clearwater valley to the headwaters of the Churchill, Jones and McAllister led the overland charge, hauling their boats and belongings 800 feet up the sheer ridge. The march ended more than 12 exhausting miles later at Lac La Loche. In a letter home to his parents, Jones recounted an ordeal that lasted three days before all their gear was shuttled to the other side of the divide. "We got so we were tripping over just about every branch, twig, stick, stone and pebble in our path," wrote Jones.

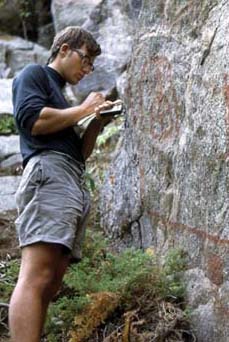

NOTED: Glen Levesque '70 documents pictographs. |

Next was a series of sprawling, gale-whipped lakes, where they encountered 4- to 5-foot swells with whitecaps and winds of 40 to 45 mph. A few days later, as they paddled north on the long, narrow Ile-a-la Crosse Lake, Levesque was separated from the others in the fog. An hour later they found each other, but in the storm-tossed waters they could've just as easily not. "As a result of this experience," wrote Jones, "we tightened up our ranks."

When they arrived at the Indian village of Patuanak, they had amassed some 300 miles. There'd been minor difficulties with the hectic pace and with intermittent sickness from untreated water and a nutrient-poor rice-and-fruit diet. Still, they'd been able to resupply at Hudson Bay posts, which kept their boats lighter and the expedition gently tethered to civilization. The next stretch would be pivotal: a 250-mile leg without any opportunity to provision.

Over the course of the next three weeks, the three enjoyed some of their finest days. They ran rapids almost daily while marveling at the wildlife—birds, including eagles, with deer, moose and a bear along the shore. They photographed stunning thunderbird petroglyphs. At a Chippewa reservation, Levesque conversed with a local chief, who told them about simmering tribal tensions and the price of furs ($35 for beaver). Although a geology major, Levesque found himself drawn to more than just rocks.

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 4 Next >Easy to print version