|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Previews

|

Easy to print version |

Last Night in Twisted River, John Irving '65

The Hanging of Thomas Jeremiah: A Free Black Man's Encounter with Liberty, By J. William Harris

Overviews: Chris Forhan '87G, Paul J. Nahin (UNH professor emeritus of electrical engineering), Tom Osenton '76 (UNH adjunct professor of marketing), John E. Carroll (UNH professor of environmental conservation), Alice B. Fogel '85G and Lindsey Carmichael '07G

In Their Own Words: Jan Campbell '86 and Sherrie Flick '89

Also of Note: Jennifer Militello '93, Thomas Newkirk (professor of English) and Lisa C. Miller (associate professor of english), Jackie MacMullan '82, Tom Chase '62 and Sarah Stizlein (assistant professor of education)

News from Theatre and Dance alumni: Aaron Sharff '07, Kirk Pynchon '92, Steve Freitas '07, Megan Godin '08 and Bunty Shakur '05

Big Heart

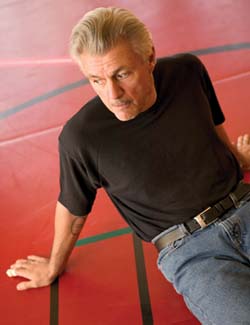

A new novel by John Irving '65 is a tale of loss, humor and hope

See at amazon.com

2004 Jane Sobel Klonsky |

"He felt that the great adventure of his life was just beginning—as his father must have felt, in the throes and dire circumstances of his last night in Twisted River." That's the last sentence of the 12th novel by John Irving '65, the sentence he gave to writer Jane Harrigan in 2005 but wouldn't allow her to print.

In the interview, which appeared in the Fall 2005 issue of this magazine, Irving talked about his writing process—how he always begins a novel with its last sentence, plotting it all out in his head, and writing backward. In his new book, Last Night in Twisted River (Random House, 2009), Irving writes about Danny Baciagalupo, a main character who is a novelist: "By the time Danny got to the first sentence—meaning to that actual moment when he wrote the first sentence down, often a couple of years or more had passed, but by then he knew the whole story. From that first sentence, the book flowed forward—or, in Danny's case, back to where he'd begun."

Irving's sprawling, big-hearted novel is about writing—and about logging, food, restaurants, Italian Americans, large women, fathers and sons. It has all the plot elements that characterize Irving's work and that his fans anticipate: disturbing relationships, freakish accidents and maimed hands, twists that cause a larger-than-life hero and a cast of richly imagined supporting characters to behave badly and sometimes redeem themselves. There is loss, humor, and, finally, hope.

The novel begins in Twisted River, a logging settlement in Coos County, N.H., in 1954. A young Canadian logger drowns, and his death brings out the half-buried memory of Dominic Baciagalupo's wife's death. Neither Baciagalupo, the logging camp's cook, nor his friend, a tough but tender-hearted logger named Ketchum, has resolved his grief. The cook's 12-year-old son, Danny, a keenly observant boy, is caught up in both men's attempts to escape their memories. And then, because of a bizarre accident, Danny must learn to cope with a memory of his own, and he and his father are forced to go on the run. The novel takes place over the course of 50 years and across northern New England and Canada as the two attempt to forge new identities and relationships.

It's been more than 30 years since The World According to Garp changed the landscape of American fiction and made Irving famous. His new novel shows that Irving's gifts—his vibrant imagination, his profound compassion, his superb craftsmanship—have only deepened over the years.

Judicial Murder

A free black man's death illuminates U.S. racial history

See at amazon.com

Perry Smith |

J. William "Bill" Harris, UNH professor of history, was researching another book when he came across the story of Thomas Jeremiah. "My first reaction was, 'Wow, someone should write an opera about this,'" he recalls. Instead, Harris wrote a book, The Hanging of Thomas Jeremiah: A Free Black Man's Encounter with Liberty (Yale University Press, 2009).

Jeremiah was a harbor pilot, one of the wealthiest free black men in British North America, and a slave owner. On the cusp of America's founding, at a moment of intense political and economic turmoil, he was falsely accused of inciting insurrection among slaves and was hanged, his body burned and buried in an unmarked grave. Harris writes that his trial and execution in 1775 in Charleston, S.C., raised questions about "what it meant to be a Briton and...an American; about who could be a Briton or an American; about what freedom itself meant."

Harris specializes in the history of the American South—his 2002 book, Deep Souths: Delta, Piedmont and Sea Island Society in the Age of Segregation, was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Writing about Jeremiah required Harris to become a colonial historian. "Jeremiah's story is known to South Carolina historians, but it isn't widely known, and I wanted to put it on the map," he says.

Harris builds his book on the intersection of the lives of three men: Jeremiah, merchant Henry Laurens, who believed that Jeremiah's death was necessary and just, and the royal governor, Lord William Campbell, who called it "a judicial murder." Harris brilliantly captures the three months leading up to Jeremiah's execution and makes the relatively small tragedy relevant to the history of the nation. Library Journal named it one of the best books of 2009.

Not much is known about Jeremiah's life—he left no letters or diaries, and there is no record of his having a family. Conversely, Laurens' letters fill 16 volumes. He built his fortune as a slave trader and wholesale merchant, was active in Charleston politics and replaced John Hancock in 1777 as president of the Continental Congress. Although less well-known than other founding fathers, he led as honorable a public life as Thomas Jefferson and was unable, like Jefferson, to denounce slavery. "He could never admit," Harris writes, "that the world of liberty and justice for men like himself, a world for which he was prepared to sacrifice all, was founded on the denial of liberty and justice to others."

Campbell, who was governor for barely two months when the trial began, tried desperately to save Jeremiah. But rumors that the British government was instigating slave insurrections to divert and weaken Americans prevented him from exerting any authority or control in the matter. A month after Jeremiah's execution, he was forced to flee the city.

"I think of Thomas Jeremiah's story as an American story, not a Southern story," says Harris. "The juxtaposition of Americans refusing to be enslaved by the British while simultaneously enslaving Africans shows how complex and elusive the meaning of 'liberty' is in our history." ~

| Overviews: |

|

|

Black Leapt In

by Chris Forhan '87G Forhan conjures up a boyhood in his evocative third poetry collection, a rich collage of images, textures, religion and loss. |

|

|

Mrs. Perkins's Electric Quilt: And Other Intriguing Stories of Mathematical Physics

by Paul J. Nahin, UNH professor emeritus of electrical engineering Nahin is a funny and charming narrator as he explores the relationship between mathematics and physics in this collection of puzzles based on topics such as Newtonian gravity, air drag, electric circuit theory and Monte Carlo probability. |

|

|

Boomer Destiny: Leading the U.S. through the Worst Crisis Since the Great Depression

by Tom Osenton '76, UNH adjunct professor of marketing The parallels between America in 1929 and today are striking, and in his third book, Osenton suggests solutions to our economic and social crises based on a new New Deal: the mobilization of Baby Boomers into an NGO to fund critical programs for Americans.

|

|

|

Pastures of Plenty: the Future of Food, Agriculture and Environmental Conservation in New England

by John E. Carroll, UNH professor of environmental conservation A companion volume to the author's 2005 book, The Wisdom of Small Farms and Local Food, this beautifully-designed edition provides ideas and sources for sustainable agriculture, food security and a new era of farm prosperity in New England.

|

|

|

Strange Terrain: A Poetry Handbook for the Reluctant Reader

by Alice B. Fogel '85G To remedy "Poem Traumatic Stress Disorder," poet and teacher Fogel offers this lovely guide, which discusses shape, word choice, sound, image, emotion and ideas in poetry, explaining in detail "why poetry can't be entirely explained."

|

|

|

Greening Your Family: A Reference Guide to Safe Food, Personal Care & Cleaning Products

by Lindsey Carmichael '07G This user-friendly guide is designed to help consumers make safe and environmentally responsible buying choices.

|

|

In Their Own Words: Descriptions of new and recent written work by the authors themselves

See at authorjancampbell.com

The Witch Who Loved Small Children |

|

|

Sherrie Flick '89

See at amazon.com

|

|

|

Also of Note... Flinch of Song: Poems by Jennifer Militello '93, Winner of the Tupelo Press/Crazyhorse First Book Prize, Militello's collection is composed of strikingly original images, which engage all the reader's senses, as in "The Museum of Being Born": "Time grew bilingual. Roads so far along/the edge they were liquids still condensing./The fog was graphite. The night B flat." |

|

|

The Essential Don Murray: Lessons from America's Greatest Writing Teacher

edited by Thomas Newkirk (professor of english) and Lisa C. Miller (associate professor of English) Don Murray's vision was to demystify writing by revealing as much as possible about the habits, processes, and practices of writers. This book carries on his work and shows the evolution of his thinking by collecting his most influential pieces as well as unpublished essays, entries from his daybook, drawings, and numerous examples of his famous handouts. |

|

|

When the Game Was Ours

by Larry Bird, Earvin Johnson, Jr. and Jackie MacMullan '82 "We were like Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali," Magic Johnson says about himself and Larry Bird. "Nobody talked about one of us without mentioning the other." In this beautifully constructed history, MacMullan draws on interviews with both men, as well as dozens of others, to illuminate their fierce rivalry, and long friendship. |

|

|

Ashen Skies of Vietnam: A Novel

by Tom Chase '62 Chase flew 467 combat support missions in the Lockheed C-130B Hercules from 1964-66, the early years of the Vietnam War. His second novel, which is loosely based on his experiences, showcases his gift for dialogue, and has an exciting plot and interesting characters. |

|

|

Breaking Bad Habits of Race and Gender: Transforming Identity in Schools

by Sarah Stizlein, assistant professor of education This book, which was awarded the 2009 American Educational Studies Association Critic's Choice Award, examines the role of racism and sexism in elementary classrooms, and offers both theoretical and practical suggestions for dealing with classroom oppression based on race and gender. |

|

News from alumni of the Department of Theatre and Dance:

|

|

Anne Downey '95G, a freelance writer who lives in Eliot, Maine, received her Ph.D. in English from UNH.