|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Web Extras

That Sweet Championship SeasonPage: < Prev 1 2 3 4 Next >

Cross-country courses were not standardized. The one at UNH was about four and half miles (the longest track run was two miles). Segments of the course had different surfaces and topography and were know as "loops": the board track loop, the lumber yard loop, the campus loop and field house loop all of differing lengths. The "board track loop" was so named because it circled a 147-yard outdoor banked wooden track. There was no indoor track at UNH back then. In winter, the track men had to shovel snow and chip ice from the board track before running on it in freezing weather in the dark—and no scholarship!

In 1924, the cross-country team shoveled snow from the track in April. |

|

It is probably just coincidence that a footrace of about four and half miles roughly equates to the dolichos, the third event added to the ancient Olympic Games. Cross country runners wearing just shirt, shorts and shoes with no special gear and few rules governing their event may come closer to the original idea of athletic competition then participants in many other sports. Perhaps like those ancient Greeks runners are seeking arete. Then again maybe they just like outdoor activity and the freedom of running.

This was the era of the Vietnam war. This was the '60s—well, sort of. New Hampshire and UNH of that era were not exactly Haight-Ashbury. Most of the members of the cross country team were in ROTC. As a land-grant college, UNH required two years of mandatory ROTC was required for male students up to this time. However, the two seniors had continued into senior ROTC and were commissioned after graduation. In the first year when ROTC was made optional one-fourth of UNH male students signed up. Yes, there were anti-war protesters on campus that year but there were more anti/anti-war protesters and "Stay in Vietnam" banners than on the other side.

Paul Sweet's team was not bothered by campus unrest. The question was whether the team was talented, trained, fit and healthy enough to be competitive in its meets. Cross country runners arrived on campus several days before the general student body. Training began and even included two-a-day work outs. Compared to what has been learned about training methods since then, and even the most advanced knowledge of that era, it was pretty basic. Most of the guys had done some running during the summer. The longest regular run was the Madbury loop of about seven miles. Runners today would consider this much too short to count as a "long run" in preparation for a 4-plus mile cross country race. Still, the team worked hard and seemed to gel competitively but also having a sense of camaraderie. George Estabrook was the captain in more than name only.

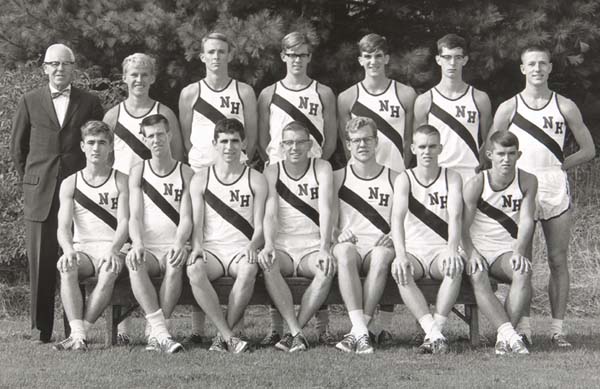

The 1965 varsity cross country team poses with Coach Sweet. Back row, from left: Coach Sweet, Wes Mattern, Charlie Morrill, Duke Wear, Rick Bell, Bob Teschek and Bob Estabrook; Front row, from left: Steve Young, Ray O'Brien, Don Wellman, George Estabrook, Rick Dunn, Pete Challoner and Steve Dudley. |

Another thing that is hard for some to contemplate today when running (jogging) is so popular and so much is known about it is that it was not always so. Kenny Moore, in his excellent book Bowerman and the Men of Oregon (Rodale, 2006), says "runners in those days were regarded as eccentric at best..." In the '50s and early '60s, it was not uncommon to wear a white T-shirt and white shorts when running ("Mama, look at the man in his underwear"). This was not recreational jogging but competitive, performance running. You had to run near your limit and being on the edge was excruciating but more in a psychological than physical sense. Runners knew nothing of cellular metabolism nor had they heard of fast twitch and slow twitch muscles. Most cross country runners knew, however, that if you ran too fast early in a race you would pay later in pain and a poor performance. A few knew this had to do with the word "anaerobic" and the phrases "lactic acid build-up" and "oxygen debt." Even in a well-paced race a runner could encounter frustration when he willed himself to run faster and his body just would not respond. Another kind of frustration was to finish and realize you had something left. You had not given your all! This sort of running could, however, also bring a joyful sense of body and mind melded in common and satisfying purpose.

So there was Paul Sweet nearing the end of his coaching career with a cross country team filled with sophomores. Of course he couldn't know there was a freshman on campus on a basketball scholarship (not Carlton Fisk '69, whose second sport was baseball) that would become arguably his greatest trackman. Jeff Bannister '80 would win the U.S. Olympic trials and make it to the Olympic finals in the premier event—the decathlon. Jeff fell in the high hurdles in that tragic 1972 Olympics. Those were the Olympics where Israeli athletes were massacred and which gave rise to the popular motion pictures Prefontaine and Without Limits. For Paul Sweet, his chances of ever winning a Yankee Conference championship were coming down to just a few seasons. The cross country meet against St. Anselm's should be a walk over but how his team would fare against other competition could not be predicted in advance.

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 4 Next >Easy to print version