|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Becoming John IrvingPage 2 of 4

|

Tom Williams died in 1990, but his widow, Liz, remembers Irving—like her husband, a motorcycle rider—visiting their cabin on Cardigan Mountain. "Eventually I'd go to bed," she says, "but I remember the two of them sitting on the couch, arguing about literature, on into the night." For his part, Yount tells stories of deer hunting with Irving, bonding as their feet froze. When the Younts' younger daughter was born and his mother-in-law came to help, his then-wife filled her in: "You have to understand there are two men in the house. The other one's John Irving.

Yount doesn't remember the first John Irving story he read, but he remembers what he did with it: He took it to Williams' house and said, "This kid who drives in from Exeter is better than anyone in Iowa." That's the Iowa Writers' Workshop, from which Yount had just received a master's degree. What jumped off the page in Irving's writing, Yount says, "was a kind of humanity that shone through his stories, and also an elegance of prose." Like Irving, Yount doesn't dwell on the how-to. "Other than maybe how to use a semicolon, I never taught him anything of value," he says. "Nor has he to this day ever taken any advice from me, which is probably why he's famous." As for Williams, Irving still thinks of him as his sternest, most loyal critic. In his memoir The Imaginary Girlfriend, Irving recalls Williams' frequent note in the margins of his stories: "Who are you imitating now?"

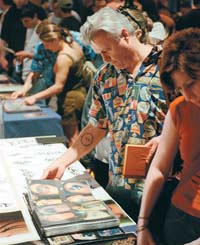

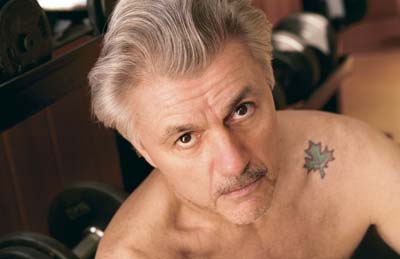

Irving had two tattoos done: a maple leaf on his shoulder, right, in honor of his Canadian wife, and the starting circle on a college wrestling mat on his right forearm.

Irving had two tattoos done: a maple leaf on his shoulder, right, in honor of his Canadian wife, and the starting circle on a college wrestling mat on his right forearm.

|

Irving looked to the two professors for direction in all things. When Yount told him that a writer should experience being an outsider, Irving set off for junior year in Vienna. He loved the independence and wrote pages by the pile, but he missed his girlfriend. When he said he wanted to come home, Yount responded in two sentences that Irving recites from memory nearly 40 years later: "Melancholy is good for the soul. Stay in Europe." Irving did stay, and his girlfriend came over. By the time he returned to Durham, Irving had a wife, Shyla, and she was pregnant.

The birth of his son, Colin, in 1965, two months before graduation, gave Irving both a lifetime focus on family and a lifetime writing theme. "From the moment I became a father at too young an age, the world became a terrifying place," he says. "The principal drive behind my novels is that something awful is going to happen. I was scared to death to be responsible for this kid." After Colin's birth, Irving parked his motorcycle and never rode it again. Fathers didn't ride motorcycles. They did, however, get draft deferments. So again, Irving became an outsider. He faced responsibilities his classmates didn't share, yet he was spared the defining decision of his generation: whether to go to Vietnam.

Instead, Irving went to Iowa. Yount and Williams had been telling him about the writers' workshop for years, and "the concept that you could get a graduate degree by 'just' writing—it was almost sinful, it was so thrilling." Williams' agent had taken Irving as a client and had just sold his first story, to Redbook magazine. So as he headed for grad school, Irving already knew he was a writer. He just needed his next "grown-up" guide, and he found him in novelist Kurt Vonnegut.

|

|

|

Once again, having a wife and child set Irving apart from his classmates. But once again, he was lucky. As long as Vonnegut could see the pages piling up, he believed Irving was better off playing with his son than sitting in class. A story Irving tells about Iowa—another student asked why Irving wasn't in class, and Vonnegut responded dryly, "If I had to guess, he's home writing"—resembles a story Tom Williams used to tell about UNH. As Liz Williams recounts it, one day in the middle of Tom's class, Irving got up and walked out. He'd had an inspiration, he explained. Tom, says Liz, thought that was great.

While in Iowa, Irving wrote his first novel, Setting Free the Bears, which was published in 1968 and sold modestly. The next year found the young family installed in a rented castle in Austria as Irving and a director tried to adapt the book into a screenplay. The birth of his and Shyla's second son, Brendan, went more easily than the writing; the movie has never been made. Irving's novels tend to cover huge spans of time, making a literal translation to the screen nearly impossible. Over the years, writers have tried to cope by using a technique called the flashforward—not, like a fast-forward, giving every event a quick moment, but rather defining certain moments as keys to a character's future.

A flashforward from Irving the once-published novelist in the castle at age 27, to Irving the publishing superstar on his Vermont mountainside at age 63, would compress a long process: Slowly, painfully, earning the luxury of writing as a full-time job. (That took 11 years, until The World According to Garp won a National Book award and sold 4 million copies in English and as many in other languages.) Venturing, over and over, down the torturous trail from book to film. (That's still going on, with many piles of wreckage along the path and three screenplays in progress.) Wrestling, always wrestling. (He competed until age 34 and coached until 47.) Divorce, followed by bad times, followed by remarriage and, at age 50, a third son, Everett.

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 4 Next >Easy to print version