|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Becoming John IrvingPage 3 of 4

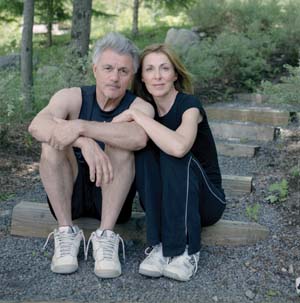

Irving at top with wife and agent Janet Turnbull.

Irving at top with wife and agent Janet Turnbull.

|

His wife, Janet Turnbull, was once his Canadian publisher and is now his agent. In the rooms and hallways of their Vermont home, photographs mark a trail through time. (Anyone who has read A Widow for One Year or seen The Door in the Floor, the movie made from the book's first section, would recognize the rows of black and white framed photos of significant family moments.) His home gym, where he spends hours working out each day, documents in photos the athletic careers of his two older sons as each achieved what had eluded their father—a New England wrestling title. Behind the desk in his office, 4-foot-tall blowups of New York Times best-seller lists show Irving on top: in 1985 for The Cider House Rules, 1998 for A Widow for One Year, and 2001 for The Fourth Hand. His Academy Award (best adapted screenplay, 1999, for The Cider House Rules) stands amid other mementoes on an office shelf; photos of the Oscar ceremony dominate a small bathroom nearby.

At a long table looking out over the mountains, Irving crafts and recrafts his central theme, which he describes as "a deeply dysfunctional, even perversely disturbing story with an improbably happy, even joyous ending." The stories wind through time, bounce past minor characters, risk losing their place, then end up right where they're meant to, much as his spoken sentences do. Here's a sample, from a conversation about Until I Find You:

"If you're going to put somebody through this kind of travail, if you're going to torture somebody over this period of time, if you're going to take a boy who is beguiling and innocent as a child and abuse him repeatedly until as an adult he almost disappears, until as an adult he's more comfortable being anybody else, including women, than he is being Jack Burns, there's no way to redeem that except to, at the end of the story, give him a sister and the possibility that he might have the first normal relationship with a woman he's ever had, and give him a father, someone who needs him to be what he is, a good son, instead of all the people he's played."

Irving in 1999 after accepting an Academy Award for the screenplay of The Cider House Rules, which took 13 years to write.

Irving in 1999 after accepting an Academy Award for the screenplay of The Cider House Rules, which took 13 years to write.

|

The good son Jack Burns, or some version of him, lived in Irving's mind for years. All writers repeat themselves, he says, and he knew that someday he'd write a book in which one of his constant themes, the absent father, took center stage. But he kept putting it off. Then in his 50s, he realized that soon he might be too old to handle the personal toll he knew this book would take. So he wrote the last sentence of Until I Find You and set about figuring out how to reach it. The process took seven years, during which things happened to Irving that would be unbelievable if they weren't true. ("People who complain that my books are bizarre," he's fond of saying, "haven't been paying attention to real life.")

First, the matter of the missing father. Irving was born John Wallace Blunt Jr., then adopted and renamed after his mother remarried when John was 6. He loved Colin Irving as his father and had no interest in hunting for another—not even when, in 1981, his mother gave him a packet of old letters that showed him, for the first time, that his biological father had wanted to keep in touch. Then, as he toiled away on Until I Find You—with many detours for screenwriting and even another novel—his past tapped him on the shoulder. A man named Chris Blunt contacted him and said, "I think you're my brother." Suddenly Irving had four new siblings (from John Blunt Sr.'s three subsequent marriages) and a revisionist autobiography.

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 4 Next >Easy to print version