|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Becoming John IrvingPage 4 of 4

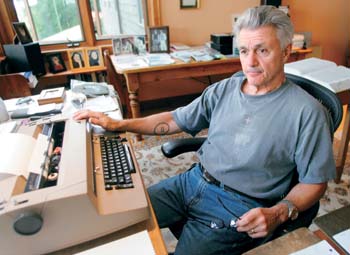

Irving writes longhand on notepads or types on an IBM Selectric: no word processing, e-mail or Internet.

Irving writes longhand on notepads or types on an IBM Selectric: no word processing, e-mail or Internet.

|

It gets weirder. Irving had already written scenes for the book in which the lost father winds up in a mental institution. Then he learned from his half-brother that in fact his biological father had spent time in a psychiatric hospital. John Wallace Blunt died in 1996; Irving never met him.

When Irving started work on Until I Find You, critic Mel Gussow of The New York Times tried to warn him: If you publish this book, you'll have to dance with your demons. He meant not just the lost father but the sexual abuse that Jack Burns suffers as a boy. Irving believed he had made peace with his own abuse—"I was 11 when a very nice woman in her 20s had sex with me," he says calmly. But writing the book revived long-buried pain. This June, Gussow's prediction came true. The first interviewers who read the galleys of Until I Find You didn't want to talk about Jack Burns' sexual abuse or his missing father. They wanted to talk about Irving's. And so, for much of 2005, the man who wrote a novel about the unreliability of memory has undertaken a book tour in which he has endlessly recounted his own worst memories for public consumption.

Ever the tough guy, Irving maintains that talking about being sexually abused caused him far less agony than writing the scenes in which Jack Burns meets the same fate. "It's the detail that gets you" is his concise explanation. He's fine answering questions about his past, Irving insists—which is lucky because he'll spend much of next year talking about it again, when the book is released in various languages around Europe. His novels, which often are set partly overseas, sell better in Europe than in the United States. Irving chooses his foreign publishers carefully and likes to be there when the books launch. He's scheduled four trips to Europe next year, and this time he'll be ready for the questions.

|

|

|

He knows he can handle them because, finally, he has moved on. Each obsession in his life, he's found, dominates only until the next one comes along to push it out. For instance, he says that his attraction to older women, the result of his childhood sexual abuse, vanished when his first son was born. Similarly, each of his books has sunk its claws into him and hung on, to be shaken off only when he begins work on the next one. The long periods he spent not writing this year—screenplays are writing, but he doesn't count them as progress along his main life path—were starting to make him nervous. So he was equal parts inspired and relieved one morning in January when, as he waited in a doctor's examining room in Rutland, Vt., he tore a page off her prescription pad and wrote the last sentence of his next book.

The story, some of which takes place in a Vermont logging camp, has been unfolding in his mind ever since. In August, flying home with Everett from Amsterdam (a place that has no trees, and somehow the absence of trees got him thinking about them), he pulled out a notebook and wrote the first chapter of the new book so fast that he worried he'd run out of paper. Now, following his usual pattern, he'll spend years getting from there to the preordained last sentence, rewriting and re-rewriting all the way. With any luck, it will be an easier slog than Until I Find You. After he'd sent that supposedly finished book to Random House, he pulled it back and rewrote all 819 pages, changing the narration from first person to third.

Knowing how his next story will end has freed him to explore how it starts. And how will it end? a visitor wants to know. He could recite the final sentence of the just-begun book from memory, but he chooses to type it. The old-fashioned novelist clearly relishes the old-fashioned sound of typewriter keys striking paper. Then the ZIP as the page is pulled out, and he hands it over: the last sentence of his next book. The sentence is, of course, a little long and convoluted, with a strange near-repetition in the middle and the twin rewards of rhythmic language and hope for our hero at the end. The sentence contains, of course, a father. And here is what he says as the paper leaves his hands: "There you go. But don't print it." ~

Jane Harrigan directs the journalism program at UNH.

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 4Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus