|

|

| current issue |  | past issues |  | send a letter/news |  | address update |  | advertise |  | about us |  | alumni home |

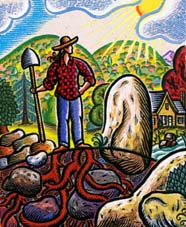

West-Running Brook

|

Rocks Rising

By Rebecca Rule '76, '79G |

|

|

I speak with a New Hampshire accent. Some think Maine--but it's not. Strange thing, most of the kids I grew up with on Corn Hill Road talk like television personalities, with inflections that evoke no place in particular. Which seems too bad, as though something has been lost of forgotten or pushed away.

My relatives talk like me, whether they're from Boscawen, Danbury, Wilmot, or East Andover--stretching a's, dropping r's and g's, making substitutions, too. Our hometowns, written as we say them, would be Boscoin, Dambry, Wilmit and East Andova. The question, "Have you seen the fox?" sends us scuttling to the silverware drawer.

In 1972 when I went off to school at UNH, folks were concerned. My first time home, their concerns seemed justified. I was talking funny, different. What was I, putting on airs?

To this day, with family or when reading New Hampshire stories to audiences, my accent thickens. When I'm teaching, it thins. I don't mind being different--writers are--but sometimes I don't want to be too different. Wouldn't want Uncle Junior to think I'm putting on airs. Don't want my students distracted.

"He's different," my Yankee grandmother would say about a boyfriend some cousin imported to try out on the family. "It's different," an aunt might say about the new purple-rose paint on the walls. Neither praise nor condemnation, "different" left room for developments. Same with "well enough."

"Do you like him?"

"I like him well enough."

"Is there too much celery salt in the potato salad?"

"I like it well enough."

Yankees may seem reserved, even cool--but the tolerance in them, in us runs deep and allows for all kinds of contraries and differences. Companion to this tolerance is an ingrained patience, one that not only accepts the stones that make the soil hard to work, but welcomes them.

I learned young to respect New Hampshire's rocky landscape. The house I grew up with was wedged between a side hill and Corn Hill Road. To add on, we had to dig. I say "we," but it was mostly my dad.

The hill was miserable digging, hard pan, until he struck a boulder, then it got worse. Progress halted. This was not unexpected. Our family credo, applied not just to digging but most things: "It'll go along like this for awhile, then it'll get worse."

Dad used a hammer and wedges to find the fault that split the stone. Rocks don't want to split. They don't want to move or be moved. Like natives, they want to stay put.

He said since you couldn't out wait a rock, you had to finesse it. That was one of his favorite sayings. Also "life's too short." Which I think is pretty much the same thing.

I grew up to be a writer of stories that stick close to what might every well be. They include rock-like obstacles I've stumbled over, herniated myself trying to persuade, been caught between, been nearly crushed by, climbed over, and--occasionally--fallen from and landed on my head. Rocks substantial enough to make a difference--roundish ones for walls; flattish ones for footpaths--but not so heavy I can't move them on my own: these are my favorites.

Here's a family story: Near the Barker homestead--a one-room cottage (two if you count the attached outhouse)--sits a boulder 20 feet high and 40 feet through if it's an inch. Years ago, when a visitor wondered how such a rock came to be in this place, my Irish grandmother pleased ignorance. "I don't know," she brogued, "t'was here when I arrived."

In my stories, I try to record the truth, near as I can figure, about people as stubbornly committed to this place as the tree sprouted from the fissure in my Irish grandmother's mysterious boulder. These stories, too, were here when I arrived. Like rocks rising in the garden, it seems a shame to let them lay.

Rebecca Barker Rule, who earned a master's degree in UNH's fiction writing program, has published two collections of short stories,Wood Heat and The Best Revenge. Rule and Susan Wheeler, a UNH English instrcutor, have jointly published Creating the Story: Guides for Writers.

blog comments powered by Disqus