|

|

| current issue |  | past issues |  | send a letter/news |  | address update |  | advertise |  | about us |  | alumni home |

Features

|

Like a Hurricane

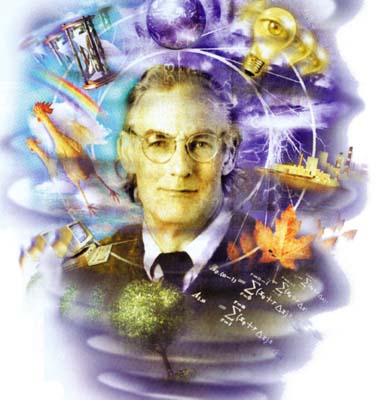

Get caught in the whirlwind of mental energy that is Dennis Meadows and you'll go places you never dreamed of. By Kimberly Swick Slover |

Easy to print version Make a comment |

Dennis Meadows stands in a circle of educators, most of whom he's never met before, digging through a canvas bag full of toys. He pulls out a few fluffy yellow balls and quietly explains the rules of the game: he will throw the balls to one person, they throw it to someone else, who passes it on to another, always in the same order. Sounds simple.

|

He throws the first ball out slowly, then another and another. No problem. He then picks up the pace of his tosses. As the balls fly around the circle, he grabs a few more toys, larger and smaller balls of varying textures, which he flings out with ever increasing speed. Balls bounce off bodies and drop to the floor, with people lunging in and out of the circle after them, when out fly--at breakneck speed--a couple rubber chickens. The circle quickly collapses into chaos.

Before the group grasps the deeper meaning of this exercise, Meadows instructs everyone in the room to find a thumb-wrestling partner. The object of this game is to achieve the highest possible number of pins. Faces contort into grimaces and grunts rise up around the room as these refined, well-educated people struggle to overpower their colleagues with their thumbs. It's a strange and amusing spectacle.

When the staff of the Concord Consortium, an educational research and development group based in Concord, Mass., invited Meadows down from the University of New Hampshire to speak to them, they probably expected a straightforward lecture on sustainable development. The group is in the first phase of a five-year project, funded by the U.S. Department of Education, to create a curriculum which teaches public-school children about the concepts of sustainability--the need to live within the earth's limits. But Meadows, co-author of two of the best known books on the subject and a international leader in the field of sustainable education, played games instead.

With the circle game, he showed the behavior of a group, or system, that has exceeded its limits. In the game, the limit is the group's ability to catch fast-flying objects; in the real world, the limit is dwindling natural resources. Thumb wrestling, on the other hand, reveals the competitive and sometimes embarrassingly irrational nature of human behavior. Teams in which members cooperated, taking turns to allow each other to score points, would have emerged as winning teams rather than as individual losers.

On his home turf, Meadows's formal title is director of UNH's Institute for Policy and Social Science Research. After a few calls around campus, I find out that unofficially, he is a free-ranging sage, a problem solver, a mentor, a strategic thinker, and a visionary. He inspires awe, he raises hackles, he overpowers with intellect and seems to magically transform ideas into productive organizations. Over the course of ten years, he has created a diverse institute that, for example, teaches corporations to work as teams, enlightens state policymakers, and helps children publish their own books. Though he has no formal teaching or research responsibilities, he does both passionately--on campus and around the world--days, nights and weekends. The age-old question arises: who is this guy?

I have a chance to find out when Meadows invites me to tag along as he gives Elizabeth McLane Bradley, a former University trustee from Hanover whom Meadows has known since his Dartmouth days in the 1970-'80s, a grand tour of his growing institute. We stop in at the Huddleston Hall offices of New Futures, the latest addition to the institute, where Meadows, an oddly practical visionary, tells us the venture will tackle the state's enormous substance abuse problem, and in the same breath, boasts that he picked up the furniture at bargain-basement prices from a going-out-of-business sale.

|

Then we're off to Thompson Hall, where Meadows has taken over the entire basement, a space once plagued by poisonous air which several other campus groups have long since abandoned. He helped to procure funding to transform the place into a safe and hospitable place, which this fall will become the new home of the institute and one of its many divisions, the UNH Survey Center.

Next we hop into Meadows's Volvo station wagon for a white-knuckle drive out to the Browne Center for Experiential Learning, located on 100 acres on Durham Point. Meadows is so deep into describing the innovative work of the center that he fails to notice he has pulled out in front of a car on Main Street, causing the driver to swerve into the other lane and lay furiously on his horn. But no matter. Ms. MacLane Bradley, a dignified and gracious visitor, is engrossed in the conversation, while I, in the back seat, wonder about the truth of Volvo's advertising claims.

We arrive safely at the Browne Center, which Meadows describes as a "good example of the way (he) works." Before Meadows's involvement, the center was but one lone building in the woods dedicated to outdoor education, without its own operating budget or staff. Intrigued by its potential as a center for experiential learning, Meadows mustered the resources to hire a director and staff, procure more land, expand the programs and add new buildings. In a few years he, along with kinesiology professor Mike Gass and Pam McPhee, director of the Browne Center, to realize the vision of former UNH physical education professor Evelyn Browne, who once lived on this land and donated it the University. Today the center is fully self-sustaining and teaches some 8,000 people a year, from corporate groups to schoolteachers and the UNH community, how to build productive teams.

Shouts and laughter in the distance draw our attention to a large wall of wood, where a small group, some at the bottom and some at the top of the wall, arms outstretched, is energetically hoisting a rather large man up and over. Meadows tells us that experiences such as these can create lasting bonds between people. "No one can do it alone; they have to access their collective knowledge. The emphasis is not on one person being a Tarzan, but in coming up with strategies that enable to whole group to succeed."

blog comments powered by Disqus