|

|

| current issue |  | past issues |  | send a letter/news |  | address update |  | advertise |  | about us |  | alumni home |

Colloquium

|

Turning Point

Alumni Historians Reveal New Hampshire Link to Gettysburg Battle By Kimberly Swick Slover |

Easy to print version |

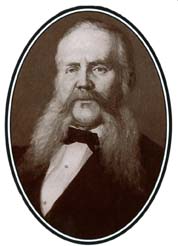

The Battle of Gettysburg, a painting completed in 1870 by George Walker, was designed by John Bachelder, who insisted on accurate depictions of the events and people. The battle claimed over 50,000 casualties, including 102 men from the 2nd, 5th and 12th regiments from New Hampshire. Below is Bachelder, the New Hampshire native who also led the effort to create the memorial at the Gettysburg, Penn., battlefield.

The Battle of Gettysburg, a painting completed in 1870 by George Walker, was designed by John Bachelder, who insisted on accurate depictions of the events and people. The battle claimed over 50,000 casualties, including 102 men from the 2nd, 5th and 12th regiments from New Hampshire. Below is Bachelder, the New Hampshire native who also led the effort to create the memorial at the Gettysburg, Penn., battlefield.

|

In war there is often a turning point, an event or moment in history that propels one side toward victory. In July of 1863--as reports of an imminent clash in Pennsylvania of the Union's Army of the Potomac and the Confederate's Army of Northern Virginia reached the North--one native of New Hampshire suspected the time had come for the decisive battle of the Civil War.

John Badger Bachelder, a lithographer and writer with an entrepreneurial spirit, rushed to Gettysburg, arriving just three days after the battle's end. There he came upon a horrifying scene: thousands of freshly dug graves and the bodies of dead and wounded soldiers in blue and grey uniforms strewn across five miles of fields. That day Bachelder launched into what would become a lifelong obsession with chronicling one of the great battles of human history.

A stickler for accuracy, Bachelder talked to Union and Confederate soldiers of every rank on the battlefield, in hospitals, at their headquarters. He crisscrossed the battlegrounds, recording the location and actions of every regiment and sketching detailed maps of the scene. And Congress eventually named him the government historian of the Battle of Gettysburg, awarding him $50,000 to write its official history. Yet most of Bachelder's voluminous body of work would never be published in his lifetime.

Historian Edward Coddington snatched Bachelder from obscurity when he stumbled on the long-forgotten papers in a corner of the New Hampshire Historical Society and published some of the eye-witness accounts in his 1968 magnum opus, The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command. But Bachelder's major contributions--his collection of letters and history of the battle--would first be published more than 100 years after his death through the diligent efforts of historians David Ladd '53 and Audrey MacDougall Ladd '54.

|

In 1990, led by Coddington's work to the historical society, the couple was shocked to see Bachelder's brittle, fading papers. They spent the next five years transcribing the letters, a job by turns tedious and exhilarating. "We nearly ruined our eyesight," admits Audrey Ladd. "But we did it for two reasons: to preserve these original sources, and to create primary sources for Civil War researchers." In 1995, The Bachelder Papers: Gettysburg In Their Own Words, a three-volume set edited by Audrey and David Ladd, was published. The Ladds then whittled 2550 pages down to 850, publishing John Bachelder's History of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1997. The two works, which have garnered high praise from critics and historians and spawned a large number of new works on the battle, are now required reading for guides at the historic Gettysburg battlefields.

The letters give voice to the survivors of a brutal battle: they tell of fellow soldiers cut down, they boast of acts of bravery and cunning, they revile those who would distort the events they had seen with their own eyes. The history, on the other hand, offers a formalized view of the battle, skillfully weaving reports of combatants from North and South into a cohesive timeline. In bringing the documents to light, the Ladds have crafted their own theory as to why Bachelder's work lay dormant for so long.

"We think that because complete accuracy was so important to him, he began to feel the letters were too unreliable, too romantic and nostalgic, and so he didn't dare to use them in the official history," David Ladd explains. "He based the history on the official reports, and Congress never published it probably because they thought it lacked originality."

|

The Bachelder works have emerged amid an explosion of interest in the Civil War in the '90s, just as thousands of other books, films, and reenactment groups are seeking to revive the dramatic events of more than a century ago. The Civil War has inspired more publications than all other aspects of American history combined, according to history department chair Bill Harris, who says its central issues still play out in American society.

"The issues of race and equality, of local versus central power, are some of the biggest issues in our history and still reverberate. And the Civil War combines all the elements--the drama, the comedy, the tragedy--of great literature," Harris points out.

Americans are still intrigued by the idea that their ancestors--people with a shared history, common heroes and a love for the goals of the American Revolution--would take up arms against each other. "There were literally cases of brother against brother, and that adds a degree of conflicting emotions. It's not as easy to pick out the good from the bad guys," Harris adds.

For the Ladds, whose ancestors were among New England's first settlers, knowing the Civil War is, for Americans, akin to knowing ourselves. "The American Civil War made our country what it is today--it's affected our politics, our language, our culture, " says David Ladd. "It's a war that is close enough to be personal since some of our great-grandparents were involved, yet far enough away that we have a sense of romance about it."

blog comments powered by Disqus