|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

On Ben's Farm

No Gift Outrightby Mylinda Woodward '97

The young boys playing near the train depot kept a watchful eye on the tall old man waiting on the station platform. He was no stranger to them-everyone in Durham knew Benjamin Thompson, the wealthiest man in town. He lived on the corner of Main Street and Madbury Road, right across from the village school, and the boys knew that if their boisterous play should provoke him, he would shake his fist and threaten to march them straight over to the Dover jail.

Benjamin Thompson was renowned for his quick temper, but as the Rev. S. H. Barnum remarked at Thompson's funeral, "beneath his peculiarities there was a kind heart and a desire to be good." That was another reason the boys kept an eye on him. If Mr. Thompson was in a congenial mood, they might be a few pennies richer before the train pulled in. He wouldn't just give them money-that was not his way-but he might take a few pennies from his pocket and throw them into the dusty road, scraping dirt over them with his foot. He'd then invite the boys to find them if they could. Benjamin Thompson worked hard for his money, and he believed others should too.

When someone in town was in need, Thompson would be among the first to offer assistance-provided that others would add to his gift. Once a family lost its home in a fire, and Thompson donated lumber for rebuilding, but insisted that neighbors help with construction. And when a man was killed at his job on the railroad, Thompson offered his entire apple crop to the family, if the railroad would transport the apples to Boston free of charge. For years he donated his hay crop to the Durham Social Library, but required that its members cut the hay and bale it. When Thompson was 22 years old, his father deeded to him the house in Durham and several farms. For Thompson, farming was strictly a business enterprise. He neither exhibited his livestock at local fairs nor wrote papers for the agricultural society. But he did take an interest in research and methods of improving agriculture.

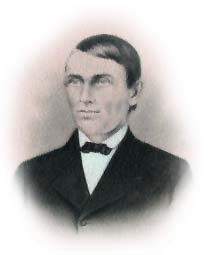

Ben Thompson was known for his temper, his wealth, and his generosity -

with string attached. Photo courtesy of UNH Museum

Ben Thompson was known for his temper, his wealth, and his generosity -

with string attached. Photo courtesy of UNH Museum

|

He had a falling out with his family when his mother died, leaving a large estate to be divided among six heirs, some of whom thought Thompson claimed more than his share. Heated words were exchanged, and Thompson made it clear to his family that they never would receive a cent from his estate.

Another fit of temper ended his relationship with the only woman he ever loved. He first proposed to her when he was 20, but she was already engaged to another man. Twenty-four years later, she was left a widow; he proposed again and she accepted. He gave her $1,000 to buy furniture for their house, but when he saw the chairs she had bought, he put them in the barn. She called off the engagement.

As he grew older, Thompson cut back on his farming enterprises but continued to increase his fortune through investments. He kept abreast of the latest developments through newspapers and correspondence with his cousin, James Joy, who had amassed a fortune in railroads. When Thompson's will was read, it turned out that the bulk of his wealth was not in the farmland that he owned in Durham, but in railroad stock.

After his death in 1890 at the age of 83, Thompson's will revealed that he had left almost his entire fortune to the State of New Hampshire to establish an agricultural school. His estate included his farm and assets totaling more than $400,000. Of course, there were strings to the gift. His will stipulated that the college was to be located on his farm in Durham. The state was required to hold his estate for 20 years and guarantee a compound interest of 4 percent on its appraised value. The will also required the state to appropriate $3,000 for the school each year for 20 years. If the state did not agree to those terms in two years, the same offer would be extended to Massachusetts instead, and then to Michigan.

James Joy was Thompson's executor, and it fell to him to defend the will against Thompson's relatives, who tried to contest it (as Ben had predicted they would). The Concord Monitor of February 11, 1891, quoted Joy as saying: "[Benjamin Thompson] felt that this state needed a good agricultural college. ... It was suggested to him that the money might do good in some other way, but his reply would be that there was no purpose for which Thompson could devote his money, which was earned by hard work, so well as this." ~

Mylinda Woodward '97 is the assistant university archivist.

blog comments powered by Disqus