|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Taking Life to the Mat

UNH wrestlers find success far from the limelight.

By Jim Collins

Photographs by Doug Mindell

This is, ostensibly, a sports story. It's about the sudden, quiet, anonymous success of UNH's wrestling program, a program that is quiet and anonymous because, at this NCAA Division I university, wrestling lurks in the off-campus, off-schedule, out-of-the-spotlight netherworld of club sports. (It's hard to be high-profile when you practice at 6:30 a.m. on borrowed mats in a tiny, aging gym attached to the local Catholic church.) More importantly, this is a story about men and women and opportunity, about different forms of dedication and about the role sports can play at any university, varsity or not.

On a cold morning in March, though, less than two weeks before the club-level national championships in Lafayette, Pa., it's hard to see the center of the story. Just five wrestlers have dragged themselves out into the gray dawn for today's practice, a distressingly low turnout. David Butler, the club's volunteer coach, turns down the rap music pulsing from a boombox and asks his wrestlers to sit together on the mat. They make a motley group around him: pasty skin, close-cropped hair, sinewy bodies, intense eyes, wild eyes, the look of hungry soldiers. Buzzing fluorescent lights cast a sour orange glow over the low-ceilinged gym. Basketballs lie strewn around piles of street clothes along one end of the room. There's no sense that this club, in just its second season of real competition, has qualified four wrestlers and three alternates for the most competitive club tournament in the nation.

Sophomore Chris Chartier had dominated the 125-lb. class at the regional championships, earning first place and a top-ranked seed at the upcoming national tournament. But his attempt to thank and inspire his teammates through an e-mail two nights ago had, instead, rankled them. He said he couldn't have done what he did without them, that when he held the trophy, he held it for all of them. They saw grandstanding in it, as if Chartier thought he was bigger than the team. Angry responses flew; riftcut through the team. The carefully fostered sense of unity and mutual support-crucial in a sport that demands self-discipline and motivation, where there is little or no external reward-was disintegrating at just the point when the wrestlers' training should be fine-tuned, just when the final push was needed.

Theirs is a punishing sport. Chartier and the other standout wrestlers typically wrestled and ran and lifted weights three or four hours a day, six days a week. Chartier, in particular, was an animal. Some days he trained alone at the ice arena, sprinting up the steps, then sprinting a lap around the oval at the top of the seats, then repeating the process until 40 or 45 minutes later he'd done each set of steps in the arena and finished what he called his "Super Bowl." The men's hockey players loved seeing his dedication. Once in a while they'd look up from their practice on the ice and yell, "Go for it, Rocky!"

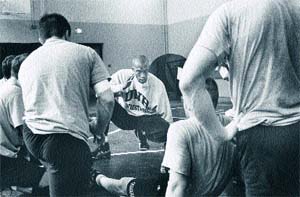

Above, coach David Butler emphasizes the importance of pre-competition

preparation.

Above, coach David Butler emphasizes the importance of pre-competition

preparation.

|

Even a small break in the wrestlers' training could cause them to lose an edge, and there's not much margin in a sport decided on points and the tiniest of mistakes. Other coaches might have ignored the incident, asked their kids to suck it up and focus on the championships. But Butler stood above his troops with his arms folded and spoke softly. "Chris isn't here this morning," he told them. "That gives us a chance to talk about what we want to do with this as a team."

David Butler, a tall, erect, muscular 47-year-old, has an aura of command about him, in the way that a U.S. senator or military general might. He joined the UNH human resources office three years ago, becoming the university's first black administrator at the vice-president level. He had taught judo and wrestling at Team Sacramento, a California-based program dedicated to training amateur athletes. He had also, along the way, worked with disadvantaged youths from the inner city, and come to believe that genuine interest and involvement can change a kid's life. He'd become a devout Christian. He'd become an expert in organizational dynamics and behavior. He knew how to walk with people of all kinds. When he casually attended a meeting for a prospective UNH wrestling club in 1999, many of those in attendance thought he was a grad student, interested only in wrestling, himself.

Page: 1 2 3 Next >Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus