|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Bill Saturno and the Temple of (not quite) DoomPage 2 of 3

Saturno went in and shined his flashlight up at the walls. There he saw a remarkably well preserved Mayan mural, partially uncovered by the looters. "I just laughed," Saturno says. "My first thought was, 'Oh my god, this is an amazing discovery!' And my second thought was, 'And I'm going to die right here. I'm going to be the skeleton that Indiana Jones finds later in the movie.'" Saturno knew immediately that the mural had to be close to 2,000 years old. The artistic style closely resembles that of the Tikal paintings, which were also found in Guatemala and have been dated to A.D. 100. But unlike the Tikal paintings, which are weather-beaten fragments, Saturno's mural is intact, and it appears to wrap around the entire room, which would make it nearly 60 feet long.

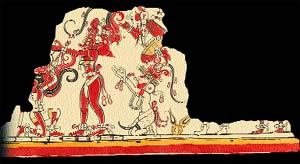

Aritst's rendering of an exposed panel of the oldest known intact

Maya mural, discovered by William Saturno in northern Guatemala. The

discovery is reported in the April 2002 issue of National Geographic

magazine. Mural reconstruction by H. Hurst

Aritst's rendering of an exposed panel of the oldest known intact

Maya mural, discovered by William Saturno in northern Guatemala. The

discovery is reported in the April 2002 issue of National Geographic

magazine. Mural reconstruction by H. Hurst

|

"It was probably a frustrating dig for them," he says, "because they wouldn't have found the polychrome pottery they were undoubtedly looking for. That kind of pottery wasn't made until A.D. 400, and there is strong evidence that San Bartolo was abandoned by that time."

Saturno attributes the mural's excellent condition to the care the Mayans had taken in sealing up the room so many centuries ago. Mayans built their pyramids onion-style; when they decided they needed a bigger pyramid, they built on top of the existing one. Saturno says that the San Bartolo pyramid appears to have six layers of construction. Before the mural room was buried under a new pyramid, Mayan workmen ceremonially killed it by filling it with rubble. But before they did that, they smeared the mural with mud to protect it. Presumably, the room remained sealed off from light and the elements for almost 2,000 years, until the looters punched through the wall.

Experts who have seen the uncovered part of the mural or pictures of it think that it depicts part of the myth of the Mayan maize god, in which he travels to the underworld and is eventually resurrected. It is clear that the mural is an important discovery. "There appear to be many more scenes and figures behind the dirt and fill of the chamber," says Stephen Houston, a professor at Brigham Young University and an expert on Mayan archaeology and writing. "The discovery is rather like finding a new Maya book, and all of us are drooling to see what's to come.

Archaelogists William Saturno [right], David Stuart, and Hector Escobedo

inspect the walls of an 80-foot-high pyramid exposed by looters at a

Maya ceremonial site in Guatemala. Saturno discovered the oldest known wall

painting of Maya mythology inside the pyramid when he wandered into a crude

looters' trench in search of shade. Photo by Kenneth Garrett © National Geographic Society

Archaelogists William Saturno [right], David Stuart, and Hector Escobedo

inspect the walls of an 80-foot-high pyramid exposed by looters at a

Maya ceremonial site in Guatemala. Saturno discovered the oldest known wall

painting of Maya mythology inside the pyramid when he wandered into a crude

looters' trench in search of shade. Photo by Kenneth Garrett © National Geographic Society

|

"The Preclassic period presents a frustrating paradox, because it had immense cities and monumental architecture, yet little is known of its society or system of rulership," Houston says. "The mural may resolve this paradox with a considerable body of well-preserved images and, we fervently hope, new hieroglyphic texts. From this we may learn more about how the Preclassic Maya linked religious belief to the organization of society."

While his guides were still off looking for water, Saturno photographed the mural and left the tunnel, saying nothing of his discovery when they returned. "You have to be very careful," he explains. "I didn't know anything about these guides. One of them actually went into the tunnel and found the mural, and I was very nonchalant about it-'Oh, yeah, we archaeologists find stuff like this all the time.'"

Saturno and his guides did eventually get out of the jungle safely. It took them a full day to get back to their Land Rovers, and Saturno didn't think about the mural at all. All he could think about was getting back alive to his wife, Jaime, and his children, Cenzo, 4, and David, 2. "On the day that we hiked out, the guides started to worry, and that's when I knew we were really in trouble. We hadn't found any water, and I started passing out from dehydration. And then we found pinuela, 'little pineapple' or poison fruit. They're about three inches long, but only the middle inch of the fruit is edible. The sections at either end are poisonous. And you're only supposed to eat one, because if you eat more than one, your tongue will start to burn."

A burning tongue seemed relatively comfortable at this point in the trip. Saturno ate several pinuela, walked 50 feet, had to rest, ate several more, walked 50 feet, rested, and so on, until he finally made it out. As he was driving his Land Rover back to civilization, his hands cracked from dehydration and started to bleed. And to add insult to injury, he got a flat tire. He was ill for several days after the trip ended and had to leave Guatemala ahead of schedule so he could recover at home in Boston.

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 Next >Easy to print version