|

|

| current issue |  | past issues |  | send a letter/news |  | address update |  | advertise |  | about us |  | alumni home |

Features

|

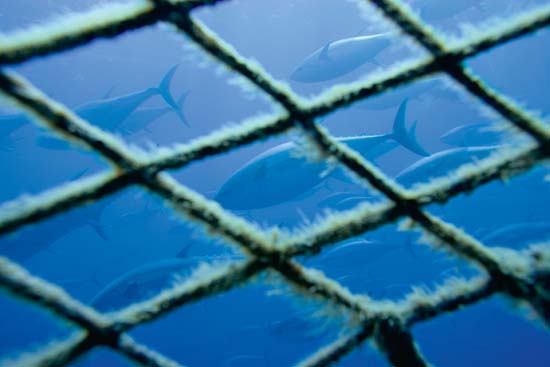

The Future of Fishing

UNH researchers work on the complicated, contentious and global problem of how to keep fish from disappearing from our oceans By Dolores Jalbert Leonard |

Easy to print version Make a comment |

|

The Pura Vida is riding the swells off Prince Edward Island on a rare clear August afternoon. An excited crew of fishermen and UNH scientists cluster to watch first mate Paul Murray struggle to rein in a giant bluefin tuna. Caught by rod and reel, this 1,000-pound fish has been hauling at the other end of a taut line of monofilament for the better part of an hour. That was the easy part. Now it's Murray's job to encourage this massive, agitated fish to settle down.

While Murray is trying to bring the fish close enough to slip a harness over its head, the giant tuna is pulling back with a force that many anglers have likened to a moving car. From the wheelhouse, Captain Ewen Clark and fisherman Cookie Murray are calling out directions, coordinating the motion of the boat to match the first mate's and giving him some leverage in this deep-sea tug-of-war.

Suddenly, the struggle is over, and the bluefin is securely lashed to the starboard side of the vessel, swimming easily along. This is the moment Molly Lutcavage has been ready for all day. She reaches over the side wielding a T-shaped tagging stick, its tip loaded with a black nylon dart, and calmly waits for a clear shot to push the dart into the base of the tuna's second dorsal fin. When the fish is released, this combination data logger and satellite transmitter will track the tuna's journey over the coming year, recording depth, temperature and location as the fish swims in a range that extends south to Brazil and east to the Mediterranean Sea.

The leviathan stares at Lutcavage as she leans over the side. It's an experience that the director of UNH's Center for Large Pelagics Research has become familiar with over the years, but one she will never get used to—looking into the immense dark eyes of a creature of the abyss. A 20-year-old giant that has crossed the Atlantic many times and has seen things she can only imagine. A fish so iridescently beautiful that when it breaks the surface on a sunny day like this she thinks of the aurora borealis. A fish so delicious that it is likely to become commercially extinct—a destiny Lutcavage hopes her research can help it evade.

|

| HOLD STILL: Walt Golet '09G prepares to tag a giant bluefin tuna, right, with an archival pop-up satellite tag that will track the fish's movements in the months to come. This fish is one of hundreds tagged by UNH researchers as part of a program to save a highly valuable and rapidly disappearing giant of the deep. |

On a campus set 12 miles from the ocean in a state that by the most generous reckoning claims 18 miles of coastline, one might think that an internationally acknowledged fisheries science expert is an anomaly. In fact, Lutcavage is part of a large community of UNH researchers, professors and students who are working to address the incredibly complicated, often contentious and thoroughly global problem of how to reverse the decline of the fisheries.

The Atlantic bluefin is only the latest installment in an old fish story, one that's been told many times over: consumers demand more fish, fishermen catch too much fish, fish run out. As this story unfolds, it almost always includes fierce arguments in which fishermen and governments clash. Fingers get pointed, not only between these groups, but to other possible causes for the fishery's collapse, like pollution or climate change. When the fish finally disappear, they take with them jobs, industries, food security—sometimes even the health of ocean ecosystems, in which the disappearance of one species can upset an intricately balanced food web.

In this breach are UNH scientists like Lutcavage, who believe that if we are not to be the last generation to enjoy the sight or taste of fish like bluefin, cod or flounder, we need to make science-based decisions that balance the fisheries' health with our need to feed a hungry planet. Their work spans a diversity of fields and tries to overcome challenges like reliably measuring an underwater population with a many-thousand-mile range and sustainably developing ways to farm fish in the ocean.

And while overfishing is often singled out as the primary driver in pushing a third of the world's fisheries into collapse, UNH scientists like Lutcavage don't see fishermen as the enemy. Instead, they view them as colleagues with the knowledge and skill that's needed to solve problems. They may come to their work on the water for different reasons, but the New England fishermen and UNH scientists who work together have the same goal in mind: healthy fisheries, capable of feeding generations to come.

"I have to say it was watching 'Sea Hunt.'" Molly Lutcavage acknowledges the source of her inspiration to become a marine biologist with a sheepish laugh. But if Lloyd Bridges' ocean adventures tempted Lutcavage to consider a life aquatic back in the '60s, it was creatures like the bluefin tuna that hooked her in graduate school.

Easy to print version

Return to Sticker Shock feature story blog comments powered by Disqus