|

|

| current issue |  | past issues |  | send a letter/news |  | address update |  | advertise |  | about us |  | alumni home |

| Spring 2009 |

|

| Departments |

|

| Alumni News |

| Alumni Profiles |

| Book Reviews |

| Campus Currents |

| Class Notes |

| Features |

| History Page |

| Letters to the Editor |

| Obituaries |

| President's Column |

| Question/Answer |

| University Research |

|

| Department Archives |

| Table of Contents |

|

Search UNH Magazine: |

Features

The Future of FishingPage 4 of 5

"Modern fishing gear is really just a modification of the kind of gear that was designed and developed hundreds of years ago," observes Chris Glass, consortium director and UNH research professor of zoology. "We use stronger materials, faster vessels and better electronics, but the way we catch fish is unchanged. What would we design if we started from scratch?"

The consortium, a UNH-based group of Gulf of Maine research institutions, brings scientists like He together with fishermen to try to answer that question. The consortium has funded more than 200 collaborative projects, including one where He worked with local fisherman Vincent Balzano to develop a modified plastic sorting grid that lets small shrimp escape. When combined with an open-top net, it also allows closely regulated ground fish like young cod and haddock to swim away.

"Gear modifications that allow fishermen to be more selective like this are good for everyone," says He.

On a spring day, about six miles off the coast of New Hampshire, UNH researchers aboard the UNH R/V Meriel B are tackling the problem of overfishing from a different angle. They watch as a knuckle-boom crane stretches over the gray-green ocean like a robotic T. rex crouched over its prey. As the crane rears up, a long tubular net, jerking with the movements of several dozen lively Atlantic cod, emerges from the water. The researchers guide the net into a blue plastic tub filled with seawater.

BABY TALK: Scientist Elizabeth Fairchild '91, '98G, '02G listens for the electronic chirps of tiny transmitters attached to winter flounder raised at UNH.

BABY TALK: Scientist Elizabeth Fairchild '91, '98G, '02G listens for the electronic chirps of tiny transmitters attached to winter flounder raised at UNH.

|

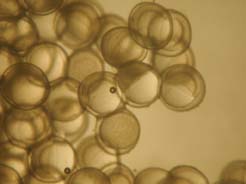

It's harvest day for UNH's Atlantic Marine Aquaculture Center, one of many such days that will deliver their crop of Atlantic cod to markets in Boston and New York. Though these fish are the offspring of wild Gulf of Maine stock, the path from hatch to harvest has been far from typical. They are among the first to be raised in the extreme conditions of the open ocean.

"The question is not whether aquaculture should be a part of how we feed ourselves, but how we can do it safely and sustainably," says director Richard Langan '80G, '92G, who has just returned to his office after an afternoon at sea. He's sunburned, happy and lugging a cooler filled with what he believes could be a small part of a solution to a looming seafood shortage. "Global demand for seafood outstripped the capacity of wild fisheries at least 30 years ago," he says. "Aquaculture, mostly in other countries, has been filling the gap ever since."

Since 1998, the center's interdisciplinary team of scientists has raised crops of Atlantic cod, halibut, haddock, flounder and blue mussels at their demonstration site off the New Hampshire coast. In the cooler are mussels, raised by a local fisherman who, with UNH's assistance, is operating the first commercial offshore, submerged mussel farm in the United States.

"Our research tells us that many species could be candidates for offshore, submerged farming," says Langan, "but given the regulatory climate and the lack of adequate funding to keep the R&D moving forward, the immediate opportunities are in shellfish like the mussels."

If there is a touch of resignation in Langan's voice, it's understandable. He has spent the past five years in the crossfire of a heated, national debate over whether aquaculture should be allowed in the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone, a 200-mile-wide band of ocean that begins three miles from the shoreline. Hamstrung by a coalition of fishermen and environmental activists, draft legislation to allow the practice has languished in Congress since 2005.

Langan understands the pro- and anti-aquaculture perspectives. In a previous life, he was a commercial fisherman, and today he directs another UNH institute that looks for solutions to coastal environmental problems.

"Back in the early '80s, I worked on a dragger, trawling for groundfish," he recalls. "I was at the wheel one night, and I counted what must have 50 other boats, each one fishing for the same thing. It was a life-changing moment. It was clear that New England's commercial fisheries could not sustain that level of exploitation."

The challenges of open-ocean aquaculture have inspired the center's scientists to come up with innovative solutions, such as a 20-ton fish feeder that can survive a Nor'easter. The issue of feed—for critics, catching smaller fish to manufacture feed for bigger fish is not a sustainable model—has been studied by UNH professor of biology David Berlinsky '81G, who has found that farmed cod thrive on feed that is part soybeans and seaweed.

"There are no isolated challenges at the offshore site," says Langan as he divides the fresh mussels for a lucky group of UNH staff working in offices nearby. "Problems drive solutions that end up being opportunities. I would like to see aquaculture integrated with other ocean activities. Could fish waste become a resource for growing marine plants that can then be fed to fish? Could the whole operation be powered by an adjacent wind farm? That's the kind of thinking we need."

Easy to print version