|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Animal MagnetismPage 4 of 4

Perry Smith/UNH Photographic Services

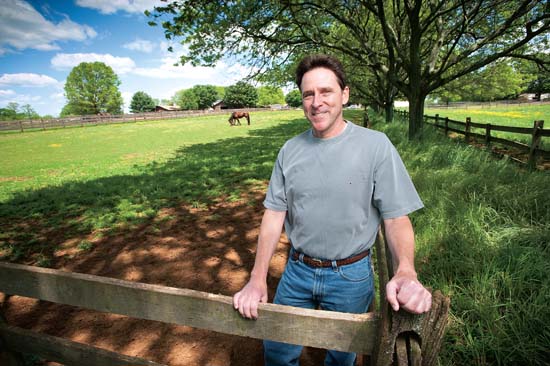

Perry Smith/UNH Photographic ServicesHORSE SENSE: Mark Mullen '79 raises standardbred horses at Fair Winds Farm in Cream Ridge, N.J. |

One of Mullen's greatest pleasures is just being on the farm with the horses in an idyllic setting during carefree periods of their lives. Mares and foals frolic in the fields until weaning time in November, and then the foals are "basically out in the paddocks living the life of Riley," he says, until it's time to prepare them for the yearling auction a year later.

The welfare of racehorses has become a hot topic in recent years as racetrack injuries and catastrophic "breakdowns"—when a horse dies or is euthanized on the track—have increased. Both economics and drug use are contributing factors. As gambling dollars have migrated from racetracks to casinos, some states have allowed racetracks to add slot machines. Profits from these "racinos" have dramatically increased the purses offered on lower-level races, encouraging owners to enter unsound horses and resulting in a rise in breakdowns. And performance-enhancing drugs are as seductive to trainers of equine athletes as they are to humans. Horses with previous injuries obscured by painkillers are the most prone to injury on the track. Racing in Europe and Canada, where drug use is tightly controlled, is much safer for horses and jockeys alike than it is in the United States.

"I do think there needs to be an international protocol with independent labs doing testing," says Meirs, who treats thoroughbreds as well as the sturdier, less injury-prone standardbreds. "But I'm not so certain how long the industry will be able to survive the public scrutiny from animal rightists and journalists—in addition to all the financial difficulty."

Perry Smith/UNH Photographic Services

Perry Smith/UNH Photographic ServicesHORSE OF A DIFFERENT COLOR: A white colt was born this spring to a standardbred mare boarding at the New Jersey farm owned by Mark Mullen '79. The foal made headlines because virtually all standardbreds are bay or brown; the last white one was born in 1998, about 200,000 births ago. In a naming contest, Blank Canvas, Mickey Blue Eyes and White Knight are leading. |

One question that frequently comes up is whether or not racehorses are, in effect, willing participants. Horses generally are born to run, says Sarah Hamilton '98, director of UNH's equine program: "When you're a hamburger on legs to a predator, you want to be ahead of everybody else in the pack."

Still, some thoroughbreds, notes Strainer, have as little interest in racing as she has in running a marathon—and these are not worth training. Others, like Zenyatta, who in 2009 became the first female to win the Breeders' Cup, clearly have the will to win. "No matter what her jockey did," says Strainer, "she would see that homestretch and swing to the outside with her ears back in a really menacing way, just galloping up the ground, and then if you watch her replays, the second that she passed that last horse, her ears would prick up like she knew—and she loved it."

Meirs worries that the public may not be able to see the devotion of owners, like some in his practice who work two or three jobs in tough economic times to be able feed their children's horses. Or the dedication of trainers like his friend K&G trainer Kelly Breen. "You will not find an animal on earth who receives better care than Ruler on Ice," Meirs says.

At Denali Stud, a horse named Serena's Song, who made more than $3 million on the track, recently was in the news when she turned 20. "People will call up," says Strainer, "and say, 'I don't agree with racing, but this horse's story touched my heart. She must be broken down now.'" Strainer is only too happy to invite the caller to come and see the beautifully cared-for mare and her newest foal. Then she waits for the words she knows will be coming: "It isn't anything like I thought! This has really opened my eyes." ~

Page: 1 2 3 4

Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus