|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Campus Currents

Lucky LeavesBy Suki Casanave '86G

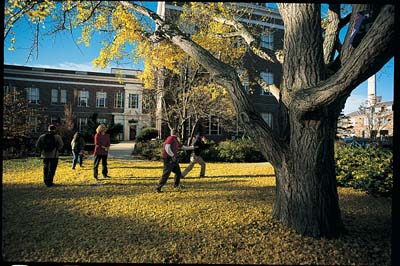

Harder than you think: Students try to catch a leaf from the James Hall gingko on Nov. 4.

Harder than you think: Students try to catch a leaf from the James Hall gingko on Nov. 4.

|

The first ginkgo tree Mary Dellenbaugh ever encountered was growing outside her elementary school in Morristown, N.J. "It smelled so bad," she remembers, "that we had to shut all the windows. It really reeked."

Today, the junior forest science major spends much of her time in James Hall, right next door to another ginkgo tree. Mercifully, this tree is male; only the females, it turns out, emit the memorable odor. And Dellenbaugh has gained a new appreciation for this ancient species, whose ancestors provided shade for the dinosaurs.

Long prized in the East for its medicinal properties, the ginkgo is especially remarkable because it's monotypic: there is only one species of ginkgo in the world, Ginkgo biloba. Bob Eckert, professor of natural resources and environmental conservation, makes a comparison to the maple tree. "Worldwide, there are more than 100 species of maple," he says. "Imagine if the only maple in the world were a red maple."

The survival of the ginkgo is all the more remarkable because it nearly became extinct, disappearing from the fossil record in both Europe and North America. Preserved by Buddhist monks in their gardens in northern China, the tree was rediscovered by western scientists in the 19th century, and now the "living fossil" is planted all over the world. Valued for its graceful form and unusual, fan-shaped leaves, the ginkgo is also disease- and pollution-resistant, making it an excellent tree for urban environments. Plus, it has amazing longevity—ginkgoes can live to be more than 1,000 years old.

At UNH, where there are about a dozen ginkgoes planted around campus, the tree is probably best known for its curious habit of dropping its leaves all at once, in a flurry of golden yellow. As president of the UNH chapter of the National Forestry Honor Society, Dellenbaugh is in charge of the annual ginkgo tree raffle. For more than 40 years, students have placed their bets, guessing when the leaves on the specimen outside James Hall will let loose. The winner receives a free pizza.

When the leaves finally do fall, the tree always attracts an audience. "Tradition has it that if you catch a ginkgo leaf as it floats to earth, you'll have good luck," says Dellenbaugh, who managed to snag one last year. "But they're actually quite difficult to catch," she reports. "Because the leaves are fan shaped, their falling pattern is very erratic. As soon as you think you have it in your hand, it darts out of reach."

This year, 70 people—students, as well as faculty and staff members—participated in the raffle. Small slips of paper filled the cardboard box in the James Hall lobby throughout October, and then into early November as the leaves held on. At 7 a.m. on Nov. 4, the leaves finally fell. The tree was bare within a few hours. Senior Matt Spinner, who came closest with his Nov. 5 prediction, won the traditional pizza, supplied by the honor society. Perhaps he ate it with friends, sitting beneath the ginkgo tree.

|

Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus