|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

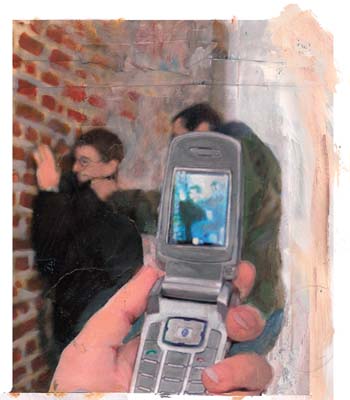

Pushing BackResearch helps parents and educators break the cycle of bullying

by Karen Tongue Hammond '64

Illustrations by Katelan Foisy

Also read Mugged by Megabytes

Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold never quite fit in. At Columbine High School in Littleton, Colo., where athletes were worshipped and just about everyone played a sport, the two preferred violent computer games and firearms. On April 20, 1999, Harris and Klebold went on a rampage, killing 13, including themselves, and shocking the nation and the world. Afterward, when investigators reported that cliques and harassment were rampant at Columbine, the media jumped on the idea that bullying played a major role in the tragedy.

Nine years later, with more perspective, many experts have concluded that bullying was only one of many explosive factors contributing to the Columbine tragedy and other high-profile school shootings that followed. But tragedies like this one have brought bullying into the mainstream of public thought as an issue worthy of study and attention. Instead of a rite of passage, or something many children endure as a normal part of childhood, bullying is beginning to be recognized by parents and school officials as a serious problem with long-term effects.

UNH's nationally recognized Crimes Against Children Research Center has been studying bullying for 15 years, and researchers there think the public attention is overdue.

|

"The way we minimize the hitting and taunting of children is unfortunate," says sociology professor David Finkelhor '78G, CCRC director. "People dismiss their suffering in a way that we would never do with adults, thinking somehow that kids are more resilient, that the experience is educational or character building, or that it's a 'fight,' not an assault."

Victimized kids find nothing positive in the experience. Schoolwork tends to suffer and relationships with peers can be permanently damaged. And studies show that although many bullies are equal-opportunity victimizers, others have a knack for zeroing in on younger children or those already dealing with challenges such as anxiety or learning disabilities.

Part of the challenge in effectively addressing bullying is recognizing the difference between youthful high spirits and damaging aggression. "Children often push, shove, bump, tease, and otherwise aggravate each other," writes Todd DeMitchell, a UNH professor of education, in his 2006 book, Negligence: What Principals Need to Know about Avoiding Liability. But students who are just testing their boundaries stop when asked to and often apologize spontaneously for inadvertently hurting someone. Bullies, on the other hand, don't act in jest. They tend to plan their taunts, teasing or physical abuse and repeat their tactics over and over, deliberately trying to harm their victim.

Edward Caron '06 was bullied by the same group of boys from second grade through sophomore year in high school--simply because he looked younger than his peers. Eventually he had the courage to let the resident bullies know he found some of their antics obnoxious--especially the "Your mom..." jokes that were the rage at the time. But the verbal taunting escalated to beatings. "It pushed me to a breaking point," says Caron, "and one day I got into my first fight."

Page: 1 2 3 4 Next >Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus