|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

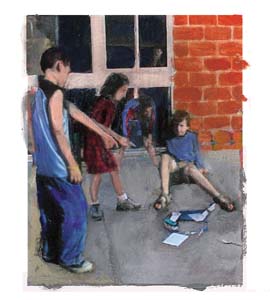

Pushing BackPage 2 of 4

Another challenge in understanding bullying and how to prevent it is that cause and effect tend to run in a muddled but vicious circle. "Depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem are common in bullied children," says Finkelhor. Most people tend to assume that these characteristics are the result of bullying, but he notes these conditions may predate the bullying and may make a child more likely to be victimized. Although not an excuse for picking on vulnerable children, this paradox can produce a cycle that is hard to break—and its effects can be lasting. A well-regarded 1995 study indicated that by age 23, chronically victimized individuals often had lower self-esteem and were more depressed than others their age.

Rich Huss '76 was one of the plump kids in junior high school. Other students were always teasing him, trying to goad him into fighting. "It was very unpleasant," he remembers. "I wasn't very self-confident and I was always outnumbered. "It wasn't until Huss reached high school and matured into a football and track standout that the taunting ended. Huss's story reflects the research. Finkelhor says that bullying tends to start in elementary school and peak during the middle school years. In some cases, like Huss's, there's a happy ending to the story: the child matures and finds his footing, the bullies grow up or go away, and time brings with it a natural healing process.

|

Students at Westford Academy, a public school in Westford, Mass., have a different experience than Caron or Huss did, according to Betsy Murphy '89, a guidance counselor at the school. Westford's zero-tolerance policy on bullying is strictly enforced, she says. When an incident does occur, "we put a stop to it," she adds, whether it takes place in a classroom or on an online social networking site like Facebook or MySpace. And everyone at Westford—teachers, coaches, lunch ladies, and custodians—understands the school's policy and works together to stop bullying so that it never escalates to fistfight. Children who enter Westford Academy after years of being bullied in elementary and middle school find an alternative education program available to support their recovery. "We offer a social and academic replacement environment for the ostracized," says Murphy's colleague, Frank Grace, who teaches in the program.

This is precisely the approach educators need to take, says Finkelhor, to help stop the tricky cycle of intimidation. Establishing a school safety plan ensures that students know where to turn if bullying threatens to escalate beyond their control. And educators should check in with children on a regular basis to see if there are problems that need attention.

Today, more attention is being paid to preventing bullying, Finkelhor says, and changing attitudes are helping to fuel progress in tackling the issue. Fewer parents, for example, see bullying as a rite of passage—something they went through and now their children must, too. "In many families, the psychological well-being of the children has become more important," he says.

The problem of sibling bullying is also attracting attention. "Danielle" (name has been changed), who graduated in 1976, knows only too well the painful results of long-term sibling bullying. Her older brothers tormented her for years. Their tactics included relentless name-calling and commentary on her "ugliness and stupidity." Recovering from the bullying, which eventually included threats of physical violence, took years of therapy for which she was further ridiculed. "It was just more proof of my stupidity, weakness, and my inability to understand that everything that happened was just 'a joke,'" she says. Only recently was Danielle able to discuss her siblings' behavior with her parents, who indicated that in retrospect, they wished they had been more aware of what was happening and had intervened.

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 4 Next >Easy to print version