|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Farming's New LandscapeNew Hampshire farmers make their way by combining innovation with tradition.

by Elibet Moore Chase '81

|

University Cooperative Extension specialist Otho Wells stands in a colorful red and green tomato field belonging to New Hampshire farmer Matt LeClair '90 and his family. Foliage from the tomato plants provides the green, but the red is not tomatoes but a plastic mulch which runs the length of the raised-bed rows. The new red mulch, Wells explains to the throng of 150 farmers gathered on this sun-streaked June evening, combined with well-aerated soil and trickle irrigation creates "a nice, cozy environment" for tomato plants to grow. Researchers at the University's Experiment Station have found that the red mulch has certain properties which enhance photosynthesis: for LeClair, this means a 5 to10 percent increase in his yield of tomatoes—a big boost for a young, struggling farmer.

The farmers who stand in the fading light of this stone-walled field have come from all parts of the state and beyond to attend a Twilight Meeting, an educational forum offered by UNH Cooperative Extension. There is a lot of handshaking and backslapping as the group gathers. Most of them already know one another—they have met at local agricultural events and some of them went to UNH together. There is a sense of camaraderie in their shared struggle to live off the land they love, relying on the whims of consumers and a sometimes fickle Mother Nature.

Tonight they will learn about the remarkable red mulch, see a demonstration of a special soil fumigation machine, get tips on weed and disease control, learn how to extend the growing season of tomatoes using high tunnels, hear strategies on more effective crop rotation for strawberries and earn credits for state certification on pesticide use. But they also will celebrate their industry and recharge their collective batteries before returning to the challenges of the small-scale family farming which typifies New England. "Farming's not for everyone," says Steve Taylor '62, the state's agriculture commissioner. "It takes a certain combination of talents and will power to make a family farm function."

Farming in New Hampshire is an ever-changing and broadly defined industry. The New Hampshire Census of Agriculture specifies that a farm is any agricultural endeavor that produces and sells more than $1,000 worth of its products—anything from lumber to honey. While there are still many large-scale dairy and apple farms, the state is seeing a new trend toward "niche" agriculture that relies on a close relationship between the producer and local consumers. More farms are run by women than ever before—16 percent—and the idea of "community supported agriculture" is being introduced, where the financial burden and risks, as well as the yield, are shared by both producers and users.

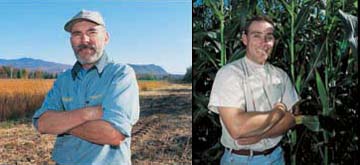

New Hampshire farmers Gordon Gray '74, left, and Matt LeClair '90 run two of the state's 2,937 farms. The number of farms has remained constant for the last 30 years, but the average acreage has decreased by 33 percent.

New Hampshire farmers Gordon Gray '74, left, and Matt LeClair '90 run two of the state's 2,937 farms. The number of farms has remained constant for the last 30 years, but the average acreage has decreased by 33 percent.

|

While the last 50 years have seen a dramatic reduction in the number of farms in New Hampshire due to economic pressures and development, since 1969 the number has remained about the same despite the fact that farm acreage has declined by 33 percent. Today there are just over 2,930 farms in the state: 30 years ago there were 2,902. "The perception is that agriculture is dying. It isn't—it's just changing and growing. It's very vibrant," says Paul Fisher, assistant professor of plant biology at UNH.

The last half century has seen unprecedented technological innovations in plant and animal genetics, plastics technology and computerization—and the University's agricultural programs, experimental work and outreach have been an integral part of this growth. Today, fruit and vegetable producers take advantage of technology which extends the season and provides insect- and pesticide-resistant cultivars; apple growers are exploring integrated pest management, stronger dwarf stock trees, and more marketable varieties; and large-scale greenhouses are using European mass production technology and innovative marketing ideas.

In the dairy industry, cows are producing more milk than ever and living longer. When mating cattle, farmers used to look for "a big tall cow and a big tall bull," says Taylor. "Now a consultant walks through the herd with a hand-held computer." By combining the computer's stored genetic information on the bulls and cows with physical characteristics observed in person, the consultant can select the attributes that will produce a better calf.

|

When Durham farmer Benjamin Thompson willed his farm to the state in 1856 to "promote the cause of agriculture," he couldn't begin to imagine the extent of his legacy at the turn of the second millennium. Many of today's New Hampshire farmers, like their parents and grandparents, came off the family farm and traveled to Durham to study on Thompson's farm—called the University of New Hampshire since 1923—in programs offered by the College of Life Sciences and Agriculture and the Thompson School of Applied Science. Even Commissioner Taylor, the state's most public farmer, is a product of Thompson's farm.

The federal government's 1862 Morrill Act provided support for land grant institutions, and the New Hampshire state legislature was quick to take action, incorporating the New Hampshire College of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts four years later as part of Dartmouth College. Thompson's historic bequest allowed the college to move 31 years later to the Warner Farm in Durham.

Agricultural research got its start in the state around the same time. Beginning in 1887, results of the Experiment Station's research were disseminated to farmers through bulletins and local newspapers. In 1911, Director John C. Kendall, Class of 1902, established the Extension Services. Today, Cooperative Extension works on the county system, although specialists will cross over county lines to provide the most recent research to the state's farmers.

Page: 1 2 3 4 Next>Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus