|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Guest Column

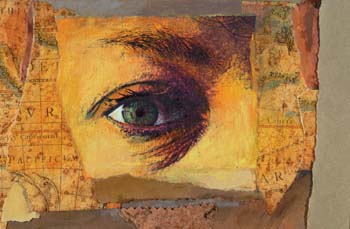

Uncharted TerritoryBy Charlotte Bacon

Maps, those crisp rectangular renditions of towns, provinces, countries. Even if a city sprawls, on a map its vastness is shrunken to a ragged, colored circle. Past a certain point, New York just doesn't spread, even it if wants to. In the abruptness of their boundaries, maps possess an authority that ignores how trees, fields and fences ramble across a county line. They correspond not to how people, animals and plants actually occupy a place, but to blunter forms of jurisdiction. Where the United States begins and Mexico ends matters a lot to the man trying to cross the Rio Grande at midnight.

|

Maps speak of a desire for human power over the landscape: a belief that the contours and contents of a place can be quantified and somewhat tamed through names, laws, knowledge. Their boldness impresses me. It is daring to insist this is the shape of New Mexico and this the nibbled edge of Cornwall. And I love names spelled out in crisp letters: Arvada and Alladin, Spearfish and Vermilion. Mamallapuram and Tiruchirappali, Aigues-Mortes and Uzès. In landscapes I do not know, maps also give me the slimmest sense of being anchored--as small as learning to say "thank you" and "hello" in Arabic while visiting Egypt.

So the lure of maplessness is slow. At first, all that matters is which route lets me avoid the Jersey Turnpike, which campground takes dogs. Then I start thinking past the flatness: What's the tallest peak in the Tetons? How many wild horses are left in the Camargue? How deep is the Nile? Every place name serves as a lid on a well of questions.

Then I become conscious, as my finger traces the red vein of the road and a river's kinking thread, that east and west are pretty vague ways to talk about direction. The map's well-ordered view of the world begins to seem less important. Perhaps it is 110 degrees and there's no room for wonder, much less fact. Perhaps I remember that the greatest gift of travel is the opportunity it provides to pay attention. I'll stash my map and peer around to see the intersection of a rainbow with a trash heap. An Indian family admiring ibis as they toss plastic plates near the birds' nest. Beautiful, shoeless Moroccans playing soccer with a deflated ball. The usual mixture of grace and squalor that defines so much human behavior, so much of our landscape.

For those moments when my judgment suspends, I also begin to notice that I am part of this place I'm traveling through. That I am next to, in relation to, that trash, that plate, those shoeless boys. Even so, I could keep moving, noticing the shadow my car or body casts as I continue on. Or I could start to assemble a more intimate map, inserting snapshots, souvenirs, journal entries. My map wouldn't have the atlas' compelling sense of authenticity—it would be jagged and untidy with personal significance—but it would be mine. But the most interesting choice at this point is to begin a conversation with the people of this land who have, after all, been looking right at me.

Once while trekking in Ladakh, we lost our guide. We reassured ourselves that so far above tree line, we would easily spot the pass we sought. Following the rim of a valley toward what looked like a notch, we saw someone running up the steep, rocky slope toward us. It is something to witness a man running at 16,000 feet in flip-flops. He was a porter for a luxuriously equipped group which, in our self-sufficient pride, we'd taken scrupulous care to avoid.

Nonetheless, this man noticed we seemed to be lost. The pass, he told us, pointing, was on the other side of the valley: 2,000 feet down, then another 2,500 feet up. Once he gestured in the right direction, it was obvious. The path snaked toward a saddle in a thin silver ribbon. The man pressed some hard candy into our palms and ran back down.

In a matter of moments he had made some of the highest mountains on Earth a place where maps were unnecessary. He didn't make our mistake any less galling or the climb less long. But he did show us the boundaries of our knowledge and help us to see what had been there all along, if we'd been willing, simply, to ask.

Charlotte Bacon is an assistant professor of English at UNH and an award-winning novelist.

blog comments powered by Disqus