|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Short Features

The Ox ManDrive oxen and see the world

by Meg Torbert

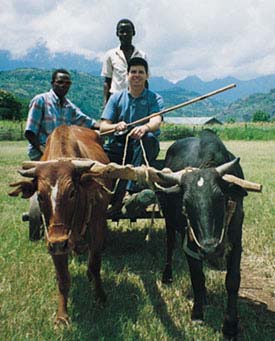

A talent for driving oxen took Drew Conroy '86 to Africa.

A talent for driving oxen took Drew Conroy '86 to Africa.

|

Drew Conroy '86 has the kind of unflappable self-confidence that comes from being able to control a team of oxen weighing more than 6,000 pounds with his voice and a thin, four-foot switch.

If they wanted to, his oxen could step on his foot, rake him with a horn or mash him against the side of a barn. Or they could just bed down and refuse to get up. But none of the above are options for oxen raised and trained by Conroy, an associate professor of applied animal science at UNH who was once described in a Smithsonian article as "purged of uncertainty." Where Conroy goes, his ox teams follow.

In a sense, however, it's Conroy who has been following oxen, starting with the day he convinced his father to load his newly-purchased Brown Swiss twin calves into the back seat of their two-door Toyota sedan. He's known across the state as The Ox Man and on campus as The Cow Man, and it's a calling that has led him to a host of far-flung experiences, from teaching Daniel Day Lewis to drive oxen to drinking a toast in cow's blood with Maasai tribesmen in Africa.

As a child growing up in Weare, N.H., Conroy learned how to train oxen from the small cadre of ox teamsters in New Hampshire who still carry on the tradition. By 1990, when he came to UNH to teach courses in dairy science at the Thompson School, he began to find that the cumulative effect of his first book, The Ox Handbook (written with Thompson School associate professor Dwight Barney '66), plus a half dozen videos and 60 articles, was to make him almost the resource of choice when it came to ox training. (A second book, Oxen, a Teamsters Guide, has just been published.)

"People were writing me from all over the world," he recalls bemusedly. Living history museums like Plimoth Plantation wanted training sessions. Tillers International, a historic farm skills preservation group in Michigan, asked him to participate in workshops to train Peace Corps volunteers and mission workers.

Then in 1994, a PBS station in Nebraska needed teams of oxen for scenes of pioneer wagons rumbling over the plains in the documentary "In Search of the Oregon Trail." Conroy appears occasionally in the film, as a pioneer walking steadily alongside the team, controlling the oxen with short, clear commands, such as "Gee" for right, and "Haw" for left.

The following summer, Conroy and his ox team were asked to appear as part of the crew in The Crucible, a film starring Daniel Day Lewis and Winona Ryder. Conroy gave Lewis lessons on how to drive Buck and Tom, his team of Devons. "He picked it up really quickly," Conroy says. Buck and Tom turned out to be quick learners, too. Before the film was finished, they learned that "Action!" meant to start moving.

In an odd way, The Crucible became intertwined with the other recent major happening in Conroy's life, a series of four trips to Africa. Conroy first visited Africa in 1995, when he joined a Tillers expedition to teach Ugandan farmers how to use oxen to plow fields. The next summer, he decided to travel to Tanzania and research land use issues related to oxen for his Ph.D. thesis in UNH's Department of Natural Resources. To finance the trip, he sold Buck and Tom to a plastic surgeon in Georgia, who wanted "The Crucible Oxen" as living lawn ornaments. "They're still there, getting fat and doing nothing," Conroy says.

Conroy has been to Tanzania three summers now, and it has been a "life-changing experience," he says. Hiring two Maasai assistants and renting a four-wheel drive vehicle, Conroy headed into the countryside near three national wildlife parks to conduct more than 125 interviews with Maasai tribesmen. The tribesman had recently turned from nomadic herding to farming large tracts. Familiar with cattle, their most prized possession, they quickly had become expert ox teamsters. Conroy wanted to know how this transformation was affecting the land and the local wildlife, so every day he headed into the bush to seek Maasai farmers.

"They weren't really interested in talking to a white man, but I would sit down on three-legged stools and introduce myself, and they'd offer tea and sour milk. This is when I'd pull out my pocket photo album, with pictures of my oxen. This made all the difference. We would walk and talk for hours about cows. They were really impressed that I had sold two oxen to come visit them. They called me a white Maasai. They were impressed with my oxen photos, too, and often a Maasai would offer one of his daughters for a pair of my oxen. But eventually we'd get to talking about wildlife, politics, government and land use, which were central to my dissertation."

Conroy discovered that using oxen enables the Maasai to cultivate hundreds of acres instead of just a few. They sell the surplus crops for cash, and are infuriated when wildlife migrate from one national park to another through their fields. "They'll use any means necessary to protect their crops," Conroy notes. Zebras, buffalo, wart hogs, elephants, even rare rhinoceros are being killed. Also, the intensified farming results in severe erosion. Ironically, he found that the oxen—which would be a great asset in many other parts of Africa—are an environmental negative in Northern Tanzania.

Now that his research is complete, Conroy's trips to Tanzania have come to an end. He thinks a lot about the farming vs. wildlife dilemma: he likes a Tanzanian government plan to hire the Maasai as wildlife managers, hoping to ensure the survival of endangered species and extra money for the Maasai.

"They told me, once you go to Africa, you'll never be cured. And it's true, I'm hooked," he says. If he does return, he'll be able to find the villages of his Maasai friends: he logged in the GPS coordinates for every one.

Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus