|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Lost and FoundRefugees from war in Sudan start a new life at UNH

by Lorraine Stuart Merrill '73

photography by Perry Smith

After four months at the University of New Hampshire, John Akok and Moses Ajou are still a bit bewildered by the array of foods available at Philbrook Dining Hall. Wearing UNH jerseys, the two freshmen greet me at the entrance to the dining hall with friendly smiles and firm handshakes. Gracious hosts, they try to pay for my lunch, even though I'm the one who asked them to meet me here. After swiping their meal cards through her machine, Carol Lamarre of the Dining Services staff confides with heartfelt enthusiasm, "They're nice boys!"

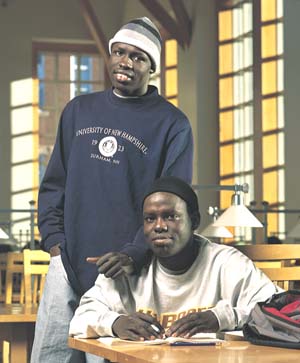

Les than two years ago, Moses Ajou (standing) and John Akok were living in a refugee camp in Kenya. Today they're freshmen at UNH and frequent visitors to Dimond Library. |

Less than two years ago, Akok and Ajou were living in a huge refugee camp in Kenya, where most meals consisted of cornmeal and water. Now in their early 20s, they are two of the "Lost Boys of Sudan," the name given to thousands of young refugees who were orphaned or separated from their parents in 1987 at the outbreak of the terrible civil war that still wracks Sudan. Children of the cattle-herding Dinka and Nuer tribes of southern Sudan, many of the Lost Boys saw their villages burned and family members and neighbors killed. There are a few Lost Girls as well, but most of the refugee children were boys who were away from their villages tending cattle when the attacks came.

Forced to flee for their lives, an estimated 20,000 to 25,000 children and teenagers trekked hundreds of miles from southern Sudan to Ethiopia. When violence broke out in Ethiopia, they made their way back to Sudan, and finally to Kenya. The boys stuck together in groups and helped each other on their odyssey. Many did not survive. No one knows how many were killed by hunger, disease, flooding rivers, lions and other wild animals. Those who made it to Kenya found shelter and food in the United Nations' Kakuma refugee camp. Akok and Ajou spent 10 years there. They received some schooling in the camp, but it was "an open prison," Ajou says. The young refugees could neither return to war-torn Sudan, nor settle permanently in Kenya. Finally, the United States government granted permanent residence to more than 3,500 of the young Sudanese--the first time such a large number of unaccompanied minors has been granted refugee status.

|

Akok and Ajou are both Dinkas, wiry and dark-skinned. Ajou is a little taller and lankier than Akok, but they both have friendly smiles, a direct gaze and the habit of listening intently when others speak. They come from neighboring districts of Bahr el Gazhel (River of Gazelles) province in southwestern Sudan. They speak clearly and thoughtfully in accented English, responding willingly to questions about their ordeal, the loss of their families and the way of life that they knew as young children. But they emphasize that their stories are not unique. "There were other children with the same problems like me," Akok observes quietly.

Akok, who was 7 years old in 1987 when northern Sudanese Muslims struck his village, has fond memories of his early childhood and his extended family in Sudan. "I used to help my elder brother looking after calves, goats and sheep," he recalls. He knew the names of all of his family's animals by the age of 4 or 5. When the village was attacked, he says, everyone scattered in confusion and panic. He ran, too, and when he looked back to the village, he saw only "huge, dark smoke." He wandered for a day on his own before meeting a cousin of his mother, who helped him to escape from the combat zone. Akok says he learned the value of kinship from this cousin's kindness to him.

Analysis and Applications of Functions is one of John Akok's favorite classes. He thinks he would like to be a high school math teacher after graduation. |

Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus