|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Lost and FoundPage 2 of 4

Moses Ajou enjoys "breakfast at night" during exam week with friends Lourdes Genao, Renai Mason and Lenaii Tolentino. |

Luckier than many of the children, Ajou fled Sudan with his uncle. "Before we set off from our village, my uncle promised to carry me on his shoulders if I couldn't walk anymore. He vowed to do whatever it took to take me to a safe haven," Ajou recalls. "I never did ask him to carry me, because there were other boys of my age who had no proper guardians but were determined to trek along." The company and care of his uncle helped ease the pain of Ajou's separation from his family. He has since learned that his father is dead, but he believes his mother and three siblings are alive in Sudan. His uncle eventually joined the army, after leaving Ajou in a camp in Ethiopia. He was killed in battle in 1989.

The resettlement of minor and young-adult Sudanese refugees is a collaborative undertaking of federal and state agencies, legions of nonprofit organizations and a corps of dedicated volunteers and foster families. Since December 2000, groups of young Sudanese have been settled in communities all across the United States, including the Greater Boston area. Those who were still minors when they arrived in the U.S. were placed with foster families, enrolled in local schools and supported through coordinating agencies in each settlement region. Those over 18, like Ajou and Akok, were settled in group apartments, with supporting services provided by resettlement agencies. Most found entry-level jobs to begin supporting themselves.

When Ajou reached the U.S., he was placed in a Chelsea, Mass., apartment with four other refugees. Their neighbors were all immigrants, he notes, from many different countries. Ajou had a job as a security officer at a factory, and he took classes at Bunker Hill Community College in Boston.

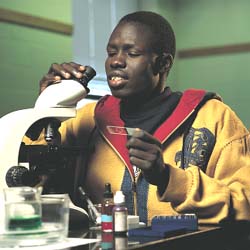

Moses Ajou meets a hydra during biology lab. He doesn't know what he wants to major in yet, but he says it won't be biology. |

Akok was one of 11 Sudanese refugees settled in two apartments in Lynn, Mass. "People weren't mean," he says of the neighborhood, "but they never talked to us." He found his first year in America difficult. "I was wanting to go back to Africa," he confesses. He was enrolled in a class at Bunker Hill while working two full-time jobs--as a document specialist at IKON Office Solutions and as a store clerk at LSG Sky Chiefs--so he could send money to his brother and two sisters back in Kenya.

Only a small handful of the Lost Boys were able to finish their schooling while growing up in the refugee camp, notes David Chanoff, a former Tufts University English professor who has volunteered to be an educational advisor to the over-18 group of refugees. In the camp schools the boys learned English from teachers trained years ago by British missionaries. Many of the young men are now working toward their graduate equivalency degrees while working full time. Some are taking college classes part time, but Ajou and Akok may be the first of the Lost Boys to enroll in a residential college program in the United States. Chanoff says that he has dedicated himself to helping the young Sudanese, not out of sympathy, but because he finds them inspiring. "They ought to be angry, hostile and aggressive, but they are just the opposite," he observes. "UNH has done something truly remarkable in admitting John and Moses. I've been in the academic world for a lot of years, and I have never heard of anything like this." He frequently sees Akok and Ajou at regular Friday-night gatherings of the Boston Sudanese group, and he says their university experience has "changed their lives."

The Sudanese connection to UNH began in the summer of 2001, when the young refugees had been in the Boston area for several months at most. Coordinators of the refugee program contacted the College of Life Sciences and Agriculture to ask if a group of Lost Boys could visit the dairy barns. Cattle are the foundation of Dinka culture and economy, and the young Dinka men were curious about cows in America. "We asked all the time," explains Carlos Nai, a 17-year-old student at Winchester (Mass.) High School, who has visited UNH twice. "There is so much milk in America! Where does this milk come from? We don't see any cows!"

Pete Erickson, an assistant professor of animal and nutritional sciences, responded with an invitation for a tour of the Dairy Teaching and Research Center. Moses Ajou was among the more than 70 Sudanese who came to UNH to see the herd of 200 Holsteins. "The guys were hugely excited to see the cattle," recalls Chanoff, who accompanied the group. "And the UNH people were excited to see the guys."

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 4 Next >Easy to print version