|

|

| current issue |  |

past issues |  |

send a letter/news |  |

address update |  |

advertise |  |

about us |  |

alumni home |

Features

Air HeadsPage 4 of 4

Mechanical engineering major Naoufal Souitat, left, and research technician Sean Wadsworth '95 work on an ozone detector similar to one carried by a "smart" balloon across the Atlantic.

Mechanical engineering major Naoufal Souitat, left, and research technician Sean Wadsworth '95 work on an ozone detector similar to one carried by a "smart" balloon across the Atlantic.

|

The successful balloon flights have opened up a new era in atmospheric research, Talbot says: "This is really the first time we've been able to put instruments in an air mass and let it drift with the current." And comparatively, the balloon missions come cheap. Unlike research aircraft, which can cost a quarter of a million dollars a day to fly and whose flights typically last only eight to nine hours, smart balloons don't need to land, can make measurements 24 hours a day and can carry miniaturized, research-grade instruments that are relatively cheap and disposable. The balloons' ozone detector, developed at UNH, cost just $1,000, a bargain compared to the $15,000 that full-sized detectors typically cost.

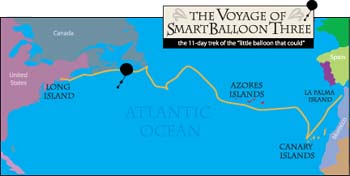

The project's researchers got the biggest bang for their buck with smart balloon number three, which, after a meandering, 11-day trek across the Atlantic Ocean, headed towards the North African country of Morocco. The intrepid dirigible, dubbed "the little balloon that could," not only exceeded all endurance expectations but measured ozone levels over the North Atlantic of 195 parts per billion—more than twice the Environmental Protection Agency's standard. What this indicates, according to Talbot, is that there's a lot more ozone being exported from North America than previously thought.

|

In addition to its scientific prowess, the balloon provided a few days of high drama for UNH scientists in Durham and a UNH student from Morocco. Junior mechanical engineering major Naoufal Souitat, who helped build the balloon's ozone detector, just happened to be at home on vacation as the balloon drifted towards foreign air space and, potentially, a politically dicey situation. A rescue mission began to form.

Phone calls were placed to embassies in Morocco and Washington, D.C. A flurry of e-mail messages and cell phone calls between scientists and engineers ensued. Letters were fired off to officials in Morocco—who wanted to know what the balloon carried—reassuring them that there were no explosives or photographic equipment aboard.

To avoid a possible international incident, researchers decided to bring the balloon down on the island of La Palma in the Canary Islands. Souitat was poised to recover the scientific instrument package. He recalls, "I was just sitting, waiting for the phone call." The call finally did come, but it was not what he wanted to hear: the recovery had been aborted.

During its descent to La Palma, the balloon apparently rammed into the craggy, volcanic mountainside, popping its Kevlar-like outer shell. With only its helium-filled inner bladder intact, it took off like an escaped circus balloon and rose to 11,000 feet.

The R/V Brown.

The R/V Brown.

|

Although the ultimate fate of the balloon remains unknown, Souitat and other undergraduates will have similar opportunities for scientific adventure in the future. EOS research project engineer Don Troop '02, research technician Sean Wadsworth '95, Souitat and others are currently at work re-engineering big, bulky instruments weighing many pounds into compact packages of tiny tubes and microchips weighing just ounces. On future balloon missions, these devices will float through the air with the greatest of ease, measuring levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide and the size and composition of aerosols or particles.

The aerosol pirates, the creators of intrepid little balloons, the toe-tapping and needle-hunting researchers—all hope to strengthen our ability to dissect and forecast air pollution. When it comes to the atmosphere, what goes around comes around, quite literally. Ultimately, this ambitious study of the skies over New England could lead to cleaner skies around the world and a more healthful environment for everyone on Earth.

Page: < Prev 1 2 3 4Easy to print version

blog comments powered by Disqus