|

|

| current issue |  | past issues |  | send a letter/news |  | address update |  | advertise |  | about us |  | alumni home |

Features

|

Earning Credit in the Underworld

When UNH students sign up for Anthropology 601 in the Belizean jungle, do they really know what they're in for? By Todd Balf '83 |

Easy to print version Make a comment |

It's Saturday, my first day in country, and Dr. Jaime Awe, my expected host in Belize, is nowhere to be found. I half expected a snafu. Dr. Awe, a pioneering Mayan archaeologist with an Amazonian-sized adventure streak, is notoriously hard to track down. After inquiring among a half dozen students milling around his project's ecolodge headquarters in San Ignacio, I know the following: Dr. Awe is either (A) the guy we just saw bouncing in the back of Ford pickup truck and en route to the team's jungle camp; (B) on his way out of the jungle; or (C) four kilometers deep (and half submerged) in a long lost Mayan cave.

Deep within the cave of Tunichil Muknal lies a crystallized skeleton (below), the remains of Mayan woman sacrificed to the gods.

Deep within the cave of Tunichil Muknal lies a crystallized skeleton (below), the remains of Mayan woman sacrificed to the gods.

|

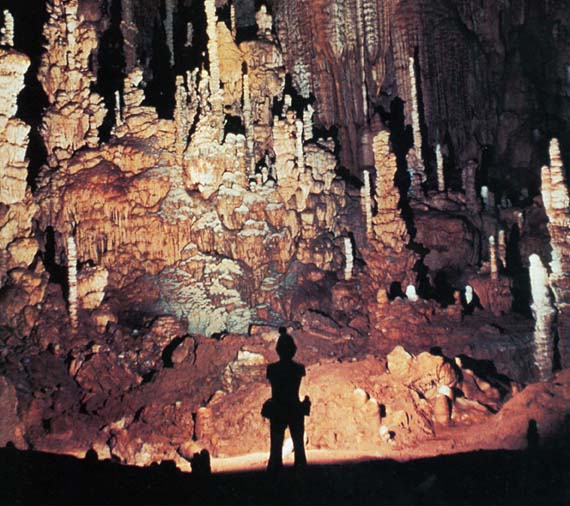

In his absence, I get a rousing student report of what I'm in for over the next few days. One student tells me about the larval botfly and that he thinks one is growing robustly in the surface skin of his forearm. I hear about deadly camp fer de lances (there are 54 species of snake, nine of them poisonous), recent cholera alerts, and the virtually unidentifiable poison wood plant for which the best rash salve is to plaster yourself upon a sun-baked car hood and singe your bare flesh. I learn about a favorite cave of Dr. Awe's where you swim in to see shiny, mineral-speckled skeletons; another that teems with fist-sized tarantulas; and another where the mojo is so creepy that students swear they hear ancient voices.

"You're going into the caves?'' asks the Belizean ticket taker at Cahal Pech, a nearby Mayan ruin unearthed by Dr. Awe and others a decade ago. I tell him I plan to. Antonio looks seriously distraught. "I'm sure it is amazing,'' he says, "but didn't anybody tell you about Chac?''

Day two. Breakfast at the San Ignacio ecolodge where the team is based begins at 6:50. I am in western Belize, a hub of Maya research, just a few miles from the Guatemalan border. I arrive at 6:45 asking about Chac.

Chac is a venerable Mayan underworld god, says Holly Moyes, one of 12 highly-energetic, graduate-level supervisors for the Western Belize Regional Cave Project. A rain deity, Chac's chief role, as described in the Mayan codices, seems to have been the sacrifice of gods and men by decapitation. It is he the Mayans may have been attempting to please when they ventured into the caves to perform their sacred, and sometimes deadly, rituals. "As you may have gathered,'' she says ominously, "you'll be hearing a lot about Chac over the next few days.''

In fact, most on the project team are holding their collective breath so as not to roust Chac. It's June but the rainy season hasn't hit yet. The result is that the scientists, including their 30 mostly UNH student workforce, have been making faster-than-expected progress this summer.

In the second of a three-season research grant, the Western Belize Regional Cave Project (WBRCP) is the first archaeological team to systematically document what's in these caves and to train future cave archaeologists, a specialty which heretofore has been limited to a field of about one. Dr. Awe.

|

At present, WBRCP is seven days deep into a 10-day, no-day-off work period. With five separate caves to map and survey this summer — Tunichil Muknal, Handprint Cave, Yaxteel Ahau, Che Chem Ha, and Baking Pot — the project is spread thin. As field study programs go, this is one of the more ambitious. It's UNH's debut field study program outside New England. There are 30 students, 12 staff, several local workmen, three trucks, and an arsenal of ropes, ascenders and other technical rock climbing gear. There's also a modest supply of 1997 T-shirts that read: "Hardcore Archaeology Isn't For Everyone.''

The most gung-ho students and staff are at the jungle camp near Tunichil, Handprint and Yaxteel, about 35 miles east of San Ignacio. Those with various maladies — coughs, colds, ankle sprains — stay in San Ignacio and daytrip to the nearer by sites like Che Chem Ha and Baking Pot. Those who are totally non ambulatory remain at the hotel where they wash, inspect, and record the tons of pottery fragments emerging daily.