|

|

| current issue |  | past issues |  | send a letter/news |  | address update |  | advertise |  | about us |  | alumni home |

Features

Earning Credit in the UnderworldPage 3 of 4

Dr. Awe says he's returning to the bush camp later this morning. I'm invited. But first he's got a dozen errands to run. There's nothing remotely easy about running a project of this size and type in the jungle. Logistics are mind boggling. An inordinate amount of time is spent patching weary trucks. Or purchasing supplies to re-stock camps. Or ferrying students to the Guatemalan border to get visas updated. This morning Dr. Awe drives his pick-up to the neighboring town of Succotz to get his workmen, then speeds back to San Ignacio for gas, groceries, a machete, a two-way radio battery, potatoes.

Meanwhile, the clock ticks. If a truck flats or a river floods, hours, sometimes days sneak by. Time is important. With logging and development (both of which are increasing rapidly) the jungle cover disappears and the caves get easier to access. If looters arrive first, the opportunity for science is lost. So, there's urgency. Fortunately Dr. Awe, a native of San Ignacio, can get things done faster than most.

UNH student Erin Darrow '99 (foreground), a civil engineering major, is at work in the Che Chem Ha Cave on her undergraduate research project, which involves surveying the site and creating a three-dimensional map of the area. Assisting her is Katie Meany '99, an anthropology major.

UNH student Erin Darrow '99 (foreground), a civil engineering major, is at work in the Che Chem Ha Cave on her undergraduate research project, which involves surveying the site and creating a three-dimensional map of the area. Assisting her is Katie Meany '99, an anthropology major.

|

It helps that everyone knows him. Rushing through town in the pick-up he waves or exchanges Spanish pleasantries with half the city. He grew up playing in the same lush "hills" he'd later help uncover as a major Mayan ruin &mdash Cahal Pech. A former striker on the local semi-pro soccer squad, he remains the only Ph.D. in archaeology from Belize. His work has helped put his hometown on the map, both for science and tourism. One consequence is that if Dr. Awe needs something &mdash a tire, a visa, a cold Coke &mdash it's taken care of.

By the time we get to the lime tree, the obscure landmark where the jeep spur road ends and the Tunachil jungle begins, it's not even noon. "We're doing better than I thought," says Dr. Awe, who just the same begins hiking at his customary breakneck pace. Next I see him he's got his shoes off, poised to swan dive into a trailside, lushly canopied swimming hole. He plunges in, paddles around, then re-boots. "I stop every time," he explains. "The Mayans had their rituals. I have mine."

The bush camp entrance appears in a cleared patch of forest close by the Tunichil cave. Life here is part Outward Bound, part Victorian jungle fantasy. Those who want the genuine experience bed in a row of tarped and mosquito netted hammocks. Others take their pick of 20 or so tents under broad-leaf canopy. Its remoteness notwithstanding, there is a homeyness about the place. Near the stream is a budding garden of cayenne pepper plants and pineapple. The cook tent, called Jose's Cafe, is a thatched roofed hut with provisions and a giant wood stove. A generator provides communal light for a few hours each night.

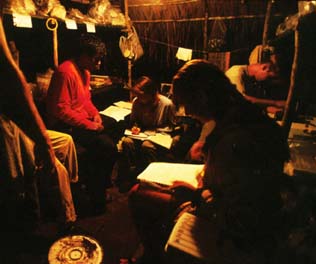

Students work in the thatched-roof field laboratory at night by low light, cataloging artifacts and calculating measurements for mapping.

Students work in the thatched-roof field laboratory at night by low light, cataloging artifacts and calculating measurements for mapping.

|

Of course, in other ways it's not like home at all. There are big vipers on the move at night. Occasionally giant coahune trees simply uproot for no good reason, toppling down with an air-sucking, branch-crashing hummphf. You hear the high hot whine of cicadas in the daytime, the guttural woofing of howler monkey troops at night. Variety is in short supply. You have one permanently damp and rotting pair of caving clothes and another that are slightly less damp for camp. Breakfast, lunch and dinner is some variation of the rice, black beans, and hot-pepper sauce theme. Your beverage is water. From a cave.

Life is in no way easy, but there's a unity that comes with living and working this way. This is clearly the heart and soul of the project and the place where a would-be archaeologist will know whether the calling is theirs. Mentally, you either embrace the jungle or reject it. You can't go halfway.

My own reaction is not unlike many of the students. I'm smitten. Partly it's the venue, partly the mission

Our first stop is Handprint Cave. No other known lowland Maya cave has its variety. There are pottery remains from rituals, but also carvings on the flowstone, and primitive paintings on the steep entrance walls. "I used to just look for pottery at caves," says Dr. Awe. "Now I look for everything." Two student teams are on high ledges above the entrance, burrowing into guano-lined crawl spaces. A half dozen others are excavating a two-meter square ditch and filtering its contents through a large, framed screen. At ground level a tape deck rings out Bob Marley's anthem, "Lively up yourself." Comically, it looks like one of those Richard Scarry "Busytown" illustrations.

"Can we get a volunteer who is really small?" shouts down Cameron Griffith, the project's pony-tailed assistant director. In the 'it's-not-pretty-but-might-just-work' department, Cameron plans to direct a human probe into a bread basket-sized hole. The idea is to rope the person, then in Poo-like fashion, heave ho from behind. This is not an exercise in terror; there are artifacts even up there. Who can resist?

Observing from down below, Dr. Awe smiles appreciatively. The buzz here is exactly what he loves, and why he can see himself spending the additional 10 years he estimates it will take to complete his research. The ultimate objective is to write the definitive book on cave archaeology in Belize. The hope is his and his students' sweat will lead to a more sophisticated understanding of what these "underworld entrances" meant to different strata of Maya society; when they were used most intensively and why; and how closely the cave ceremonies mimicked one another. Ulimately cave archaeology may help answer the biggest riddle of all: Why did the once flourishing Maya civilization, home to some two million people in Belize alone, suddenly and irrevocably collapse?

Page: 1 2 3 4 < Previous Next >

Easy to print version