|

|

| current issue |  | past issues |  | send a letter/news |  | address update |  | advertise |  | about us |  | alumni home |

Features

Earning Credit in the UnderworldPage 2 of 4

Today I'm assigned to work Che Chem Ha with Holly, Jen and four students. The highly aerobic hike in is a mile up a steep, mostly sun-exposed slope. By the time we get to the squat cave entrance I'm grunting louder than the buzzing cicadas. Jen repeats the project rules. Nobody goes in or out of the cave alone. Helmets must be worn. Watch your step. The footing is treacherously slick, your visual perspective reduced to the throw of light from a bobbing headlamp. There are no tarantulas at Che Chem Ha, but there are fruit bats, talus spiders, Godzillian cockroaches, and a frenetic colony of dive-bombing swallows. On the plus side, Che Chem Ha is a dry cave.

Unlike surface site digs, where the cultural remains are buried and roughed up over time, a cave site like Che Chem Ha features little if any disturbance. The water-carved karstic limestone walls have preserved things just as the Mayans left them —an invaluable asset to archaeologists trying to figure out what the native people were doing in here. At the visceral level, says Jen, it's a rush to explore. "I really hate heights," she says, clambering up a homemade jungle ladder, "but I find I'll do anything to see a polychrome Mayan pot."

Students outside of Handprint Cave draw maps of the cave's interior and dig for and bag artifacts.

Students outside of Handprint Cave draw maps of the cave's interior and dig for and bag artifacts.

|

In cave archaeology the Cracker Jack prize is uniquely at the top. At Che Chem Ha, we see about 50 pottery vessels, some more than 2,000 years old. Most are gourd-shaped, used as containers for liquids and foods used during rituals. All are smashed to one degree or another, an exercise that released the spirits the Maya believe were harbored in their meticulously crafted ceramics. The pottery is every place imaginable, lining the high cave balconies, tucked into corridor alcoves, stowed in a deep, secret chamber. In the most remote chamber of all stands a small limestone stelae or monument, a rare find in caves and one that archaeologists believe may have played a part in the worship rituals of the Mayan elite.

Of course, none of this stuff is easy to get at. This is where the high physical demands of cave archaeology come into play. You scramble up crud-filmed rock, belly crawl under a swollen, pinched ceiling, rappel by slimy rope into a sacred, bat-filled stelae chamber. At day's end you feel like you've been under a rock all day.

Deprived of light, students say they often feel prematurely fatigued and a little out of it. Mapping and cataloguing is tedious. In the stupefying mental and physical isolation, fears sometimes get amplified. Wires cross. Justin Miller, a UNH student from Gorham, Maine, mishears someone and as consequence lives in mortal dread of what he believes are "fertile ants." On the long walks in and out to Che Chem Ha Justin hurries noticeably, scanning all the while. After several days somebody finally clues him in. It's fer de lance, not fertile ants. Justin confesses great relief. A big deadly snake he can handle. Hordes of murderous ants he cannot.

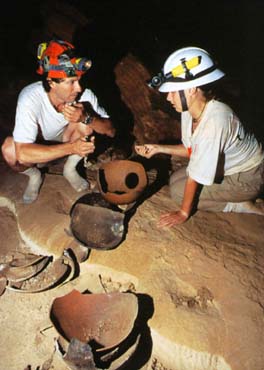

Assistant Professor Jaime Awe with Sherry Gibbs, a graduate student from Trent University, examine shards of pottery which the Mayans smashed in caves to release spirits they thought were harbored within the vessels.

Assistant Professor Jaime Awe with Sherry Gibbs, a graduate student from Trent University, examine shards of pottery which the Mayans smashed in caves to release spirits they thought were harbored within the vessels.

|

Well before sunset, we're out of the caves and on our way back to San Ignacio. We've discovered nothing new, but have polished off a good chunk of mapping, a numbingly awkward and complicated task in maze-like caves. On the road back we spot the towering pyramid of Xunantunich as it crests above distant jungle. More than a millennium after it was built, Xunantunich, along with a nearby Mayan pyramid at Caracol, are still the two tallest structures in Belize. Vast numbers of other structures remain entombed in deep jungle. Thousands of caves, too. Says Holly, "On one level it's thrilling and on another it's really frustrating to know we haven't even begun to scratch the surface of what's here."

It's Monday, day three. Word travels quick. Dr. Awe is here. As it turns out, he was the guy in the back of the truck. More 'Let's Go' than professorial in a T-shirt, soccer togs, and sport sandals, the 43-year-old Dr. Awe is in a buoyant mood. Over breakfast he gleefully describes a new development at Handprint Cave. Jade jewelry? somebody asks. Obsidian blades? Stelae? No, announces Dr. Awe, but they have just landed a moonshot onto a slim, yet-to-be explored ledge. (Translation: Using ropes and technical climbing gear, two students have ascended to a new and precarious perch.)

"They're up there?" shrieks Chris Helmke, the project illustrator and a graduate student from McGill University. It's only mock horror — I think. Dr. Awe plays along; with a dismissive wave of the hand, he says, "Ah, they signed their waiver releases." He glances my way. "Field school humor."

Page: 1 2 3 4 < Previous Next >

Easy to print version